After South Africa’s mammoth 214-run victory in the deciding One Day International at Mumbai on Sunday (which was the second-largest defeat for India in terms of runs), team director Ravi Shastri was not a happy man. While one could understand the former Indian captain’s rage at the abject capitulation of his wards, Shastri decided to vent his frustration somewhere else – after the match, Shastri is alleged to have abused the curator of the Wankhede Stadium Sudhir Naik for not making a surface conducive to spin which, according to the team director, would have served India's cause better.

Understandably, Naik was not amused and shot off a complaint to the Mumbai Cricket Association. While Ravi Shastri was appalled at the sight of his bowlers being hammered all over the ground, his decision to blame the pitch, rather than his team, makes him a sore loser.

He alleged that the Wankhede pitch was not helpful for India. The argument goes that instead of making a spinning, turning wicket, Naik prepared a flat surface thus making Indian bowlers easy fodder for the rampaging trio of Quinton de Kock, Faf du Plessis and AB de Villiers. In Shastri’s eyes, it must have been the pitch that was responsible for Bhuvneshwar Kumar and Mohit Sharma unable to deliver any yorkers or slower balls. And of course, the pitch probably changed character in the innings-break because in the hands of Dale Steyn and Kagiso Rabada, the ball seemed to zip through to the keeper.

Can India play spin?

But would India really have had an advantage, even if all the five tracks in the ODI series had been spinning dustbowls? Sure, Indian spinners might have got some more purchase for their skills. But is there any guarantee that their batsmen would have found life easier?

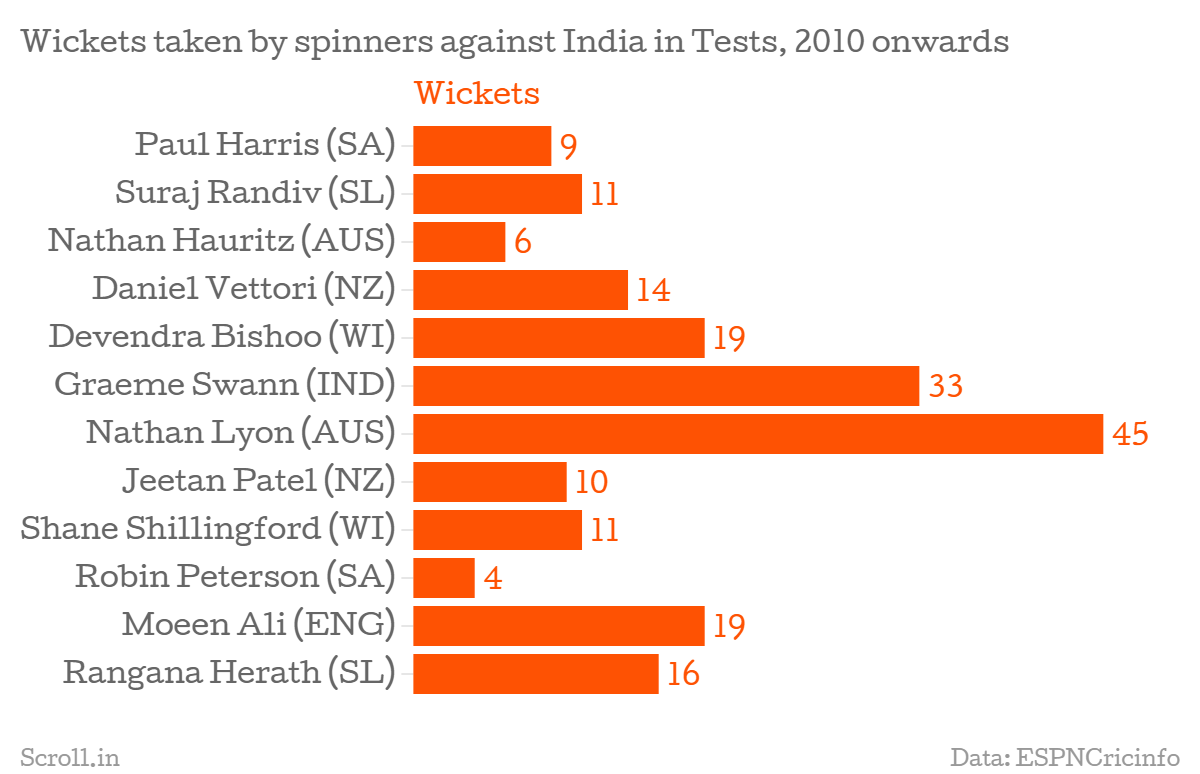

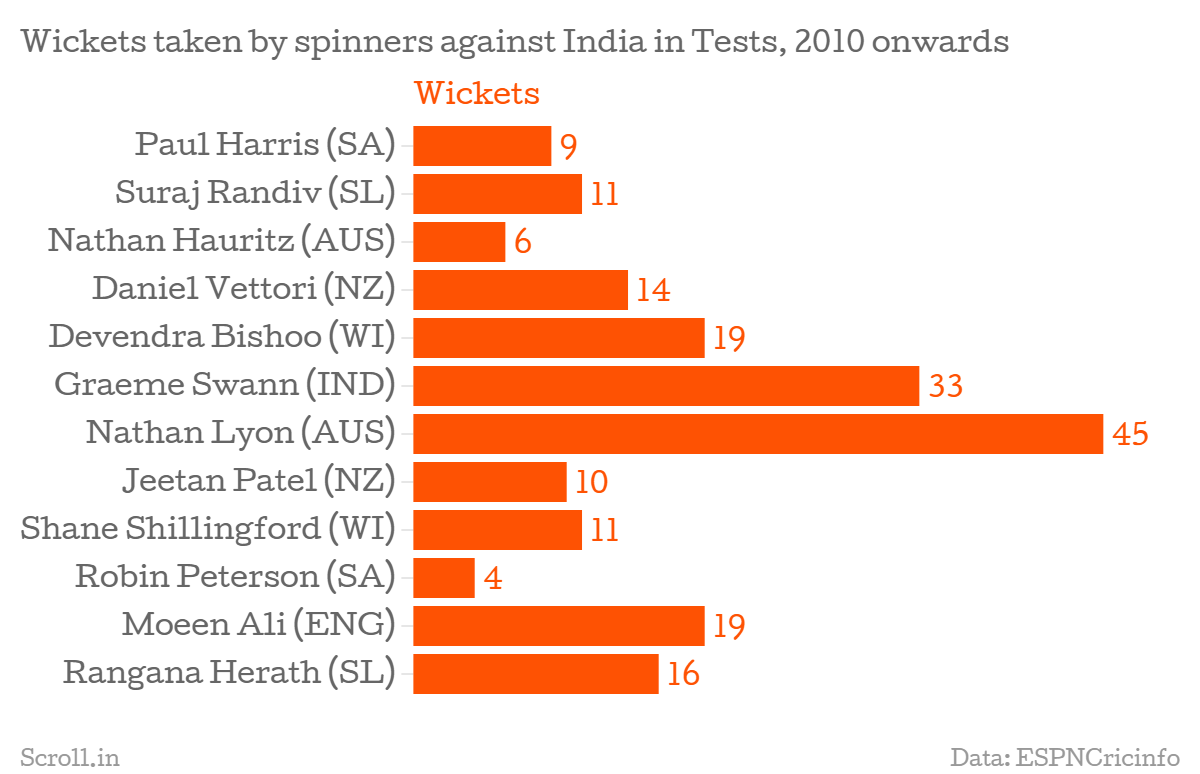

Not really. From 2010 onward, spinners as varied as Suraj Randiv (Sri Lanka) to Graeme Swann (England) to Nathan Lyon (Australia) have thrived against India in Test matches. Clearly the old adage that “Indians are masters at playing spin” clearly does not hold true anymore.

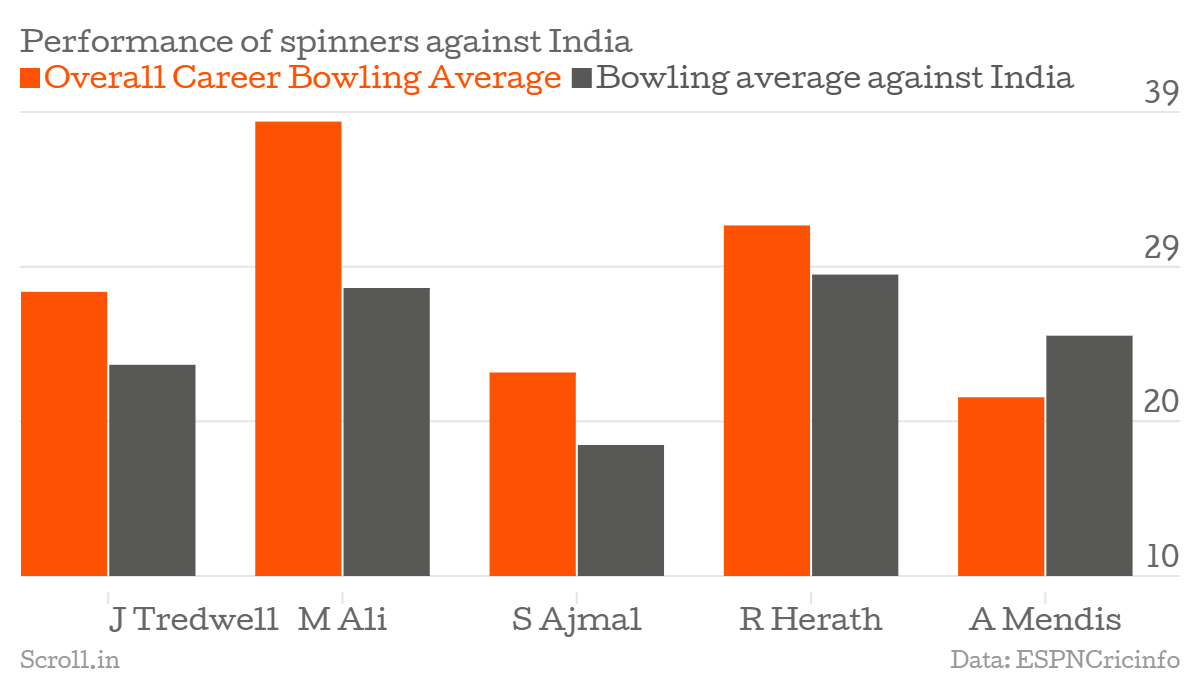

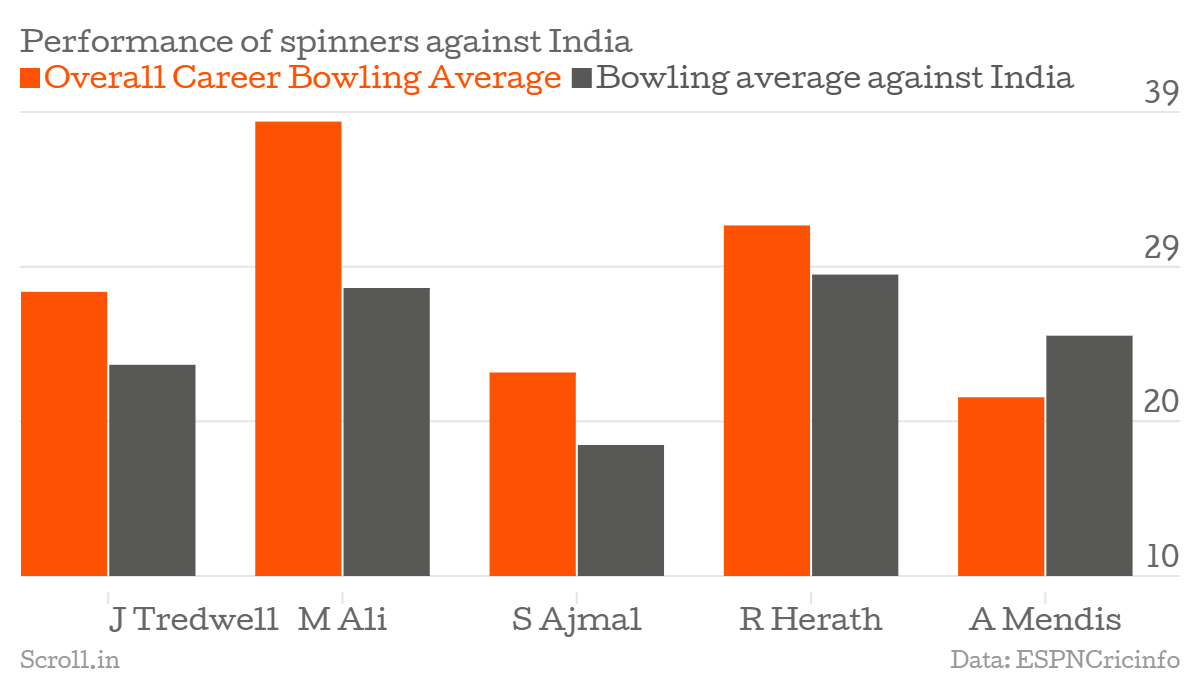

The situation is a little better in ODIs, but not by much. Quite a few spinners in international cricket would not mind having a go at Indian batsmen, chief among them being Pakistan’s Saeed Ajmal and England’s Moeen Ali.

So while Shastri’s rant against the surface at the Wankhede stadium might lead to the curators dishing out sufficiently spin-friendly tracks in the forthcoming Test series, there is always the chance it could come back to bite India. While South Africa have already shown they have quality in their pace-bowling ranks, their spin quotient, for once, does not look unimpressive. While Rabada, Steyn and Morne Morkel topped the wicket-taking charts in the just-concluded ODI series, a little-known fact that went unnoticed was that Imran Tahir had finished in fourth place, ahead of India’s spin trio of Harbhajan Singh, Axar Patel and Amit Mishra.

Excuses galore

It might also have escaped Shastri’s mind that when England toured India in 2012, their spin duo of Graeme Swann and Monty Panesar completely outbowled their Indian counterparts, playing a big role in England clinching a series win in India after 28 long years. But perhaps, it’s symptomatic of the larger excuses culture that has recently permeated Indian cricket. Every loss is followed by excuses ranging from the bizarre to the exasperating. Largely, it seems to be a smokescreen to divert attention from the myriad challenges Indian cricket seems to be facing. Instead of abusing curators for doing their job, perhaps Ravi Shastri could try his hand at fixing some of those problems.

Understandably, Naik was not amused and shot off a complaint to the Mumbai Cricket Association. While Ravi Shastri was appalled at the sight of his bowlers being hammered all over the ground, his decision to blame the pitch, rather than his team, makes him a sore loser.

He alleged that the Wankhede pitch was not helpful for India. The argument goes that instead of making a spinning, turning wicket, Naik prepared a flat surface thus making Indian bowlers easy fodder for the rampaging trio of Quinton de Kock, Faf du Plessis and AB de Villiers. In Shastri’s eyes, it must have been the pitch that was responsible for Bhuvneshwar Kumar and Mohit Sharma unable to deliver any yorkers or slower balls. And of course, the pitch probably changed character in the innings-break because in the hands of Dale Steyn and Kagiso Rabada, the ball seemed to zip through to the keeper.

Can India play spin?

But would India really have had an advantage, even if all the five tracks in the ODI series had been spinning dustbowls? Sure, Indian spinners might have got some more purchase for their skills. But is there any guarantee that their batsmen would have found life easier?

Not really. From 2010 onward, spinners as varied as Suraj Randiv (Sri Lanka) to Graeme Swann (England) to Nathan Lyon (Australia) have thrived against India in Test matches. Clearly the old adage that “Indians are masters at playing spin” clearly does not hold true anymore.

The situation is a little better in ODIs, but not by much. Quite a few spinners in international cricket would not mind having a go at Indian batsmen, chief among them being Pakistan’s Saeed Ajmal and England’s Moeen Ali.

So while Shastri’s rant against the surface at the Wankhede stadium might lead to the curators dishing out sufficiently spin-friendly tracks in the forthcoming Test series, there is always the chance it could come back to bite India. While South Africa have already shown they have quality in their pace-bowling ranks, their spin quotient, for once, does not look unimpressive. While Rabada, Steyn and Morne Morkel topped the wicket-taking charts in the just-concluded ODI series, a little-known fact that went unnoticed was that Imran Tahir had finished in fourth place, ahead of India’s spin trio of Harbhajan Singh, Axar Patel and Amit Mishra.

Excuses galore

It might also have escaped Shastri’s mind that when England toured India in 2012, their spin duo of Graeme Swann and Monty Panesar completely outbowled their Indian counterparts, playing a big role in England clinching a series win in India after 28 long years. But perhaps, it’s symptomatic of the larger excuses culture that has recently permeated Indian cricket. Every loss is followed by excuses ranging from the bizarre to the exasperating. Largely, it seems to be a smokescreen to divert attention from the myriad challenges Indian cricket seems to be facing. Instead of abusing curators for doing their job, perhaps Ravi Shastri could try his hand at fixing some of those problems.

Scroll has produced award-winning journalism despite violent threats, falling ad revenues and rising costs. Support our work. Become a member today.

In these volatile times, Scroll remains steadfastly courageous, nuanced and comprehensive. Become a Scroll Member and support our award-winning reportage, commentary and culture writing.