Milagres Costa of Nuvem village stared in dismay at his paddy fields flooded with stagnant water from the monsoon rains in July, spelling doom for the crop. An under-construction highway – the 11.9 km Margao Western Express Bypass, a stretch of National Highway 66 meant to skip South Goa’s commercial town Margao – has disrupted the hydrology of the area, obstructing the free flow of excess water. This has impacted the low-lying fields of Nuvem, once known as a rice bowl.

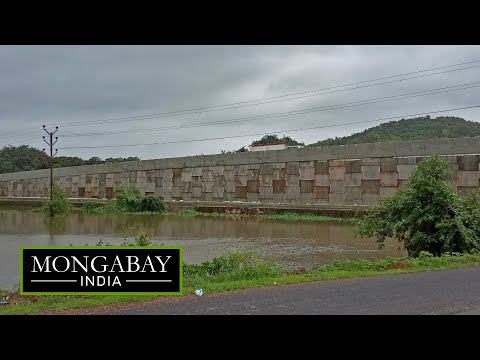

The highway has been laid through a portion of Rumdem lake in this tribal area, as it winds through the Sal River’s floodplains. A 60-metre wide, 4-metre high and 2-km long embankment is obstructing the flow of water.

“There are 4 lakh square metres of fields in Nuvem, which get their water from three bhandaras [lakes],” said Costa, former head of Nuvem Village Farmers Club. “Around 30% to 40% of the main Rumdem bhandara has been blocked by the bypass highway. Before 2014, 80% of the fields were cultivated twice a year. Last year, less than 5% was cropped in the kharif [monsoon] season and 12% in the rabi [winter] season. During the monsoon, the fields are totally flooded. The pipes under the highway for cross-drainage are inadequate and the water stagnates. We are hit very badly.”

Since 2014, when contractors began dumping some 24 lakh cubic metres of mud, including sludge from a nearby industrial estate, in an area less than 100 metres from the Sal River, it sounded the death knell for the rice fields in the area, said Costa.

The most fertile land in Goa is sandwiched between the Western Ghats in the east and the Arabian Sea on the west. Scores of rivers from the mountain range cross the narrow plains before draining into the sea. The coastal areas have numerous backwaters that provide a vital lifeline to farmers and fisherfolk. In recent years, hastily designed and ill-planned infrastructure projects have destabilised the delicate hydrology in the state, where a majority of the people depend on farming and fishing for their livelihood.

Bad infrastructure design

The state government has admitted to the bad design of the Margao bypass, but that’s scant consolation for farmers. “There are certain places on the Western Bypass where the consultant may have made a mistake in the design. I will not deny that,” Goa Chief Minister Pramod Sawant told the legislative assembly in August, when lawmakers flagged concerns over flooding, including the danger this posed to Margao city.

“Since 2008, we have raised 150 objections to this bypass alignment at public hearings,” said Zarina D’Cunha of Nuvem Civic and Consumer Forum. “We are fed up. Besides the fields that are flooded, floodwaters have reached our doorstep. Is it fair? Where do we go? We were asking that this portion on the floodplains be constructed on stilts [for water to pass]. But we were being told there’s no money for that.”

Activist Siddharth Karapurkar said he wrote several articles in local newspapers to highlight the Sal River’s origins from the Verna hills and the site of a temple in Nuvem village. “I wanted to broad-base the concern for Sal,” he said.

The authorities, however, declined to bear the increased cost of the road on stilts. When the area flooded between June and August and proved that concerns of local residents were all too real, Chief Minister Sawant promised to find the money to construct a contentious 2.35-km stretch in Seraulim and Benaulim villages on stilts.

Angry residents protest

The chief minister’s admission of faulty engineering cuts little ice with angry residents. “We are not planners,” said D’Cunha. “Planners plan in the dry season. But we live here. In the monsoon, the floodplain, as the name suggests, is flooded, with water gushing down from the hill range to the east. Yet, despite repeated and ongoing protests from villages along the floodplain, the authorities went ahead with this alignment.”

Affected residents say they are never sure if the road alignments are chosen keeping in mind property and land purchase considerations made by corrupt politicians. Be that as it may, such infrastructure development threatens rural livelihoods in many areas.

Work has now practically stopped at Seraulim and Benaulim villages. “There’s already flooding every year in Benaulim, where hutment dwellers have to be evacuated to a stadium by disaster management teams,” said activist Avinash Tavares. “Five years ago, when they had a consultation, I asked if they had studied the water volumes that drain this area in the monsoon before siting the road alignment here.” He did not receive a satisfactory reply.

The controversy over the Margao bypass has reached the High Court of Bombay at Goa. It has instructed the Public Works Department to immediately send a proposal that includes building box culverts under the road instead of the earlier envisaged pipe culverts. The court has however ruled out building the road on overbridges because that would double the cost of the project. The authorities have said Sal River will be dredged and cleaned up to allow speedy drainage of monsoon water.

Disturbed hydrology

The Margao bypass is not the only stretch of highway expansion and widening that has become contentious for disturbing the region’s hydrology. Since 2014, 14 road-widening projects on 250 km of north to south and east to west highways, which would cost an estimated Rs 86 billion, have been put on the fast track in the state.

Goa’s topography and hydrology present a daunting challenge to civil engineers. With a riverine system that is both tidal and rainfed, this small state has nine major and two minor river basins with 41 tributaries that are fed by a wide network of streams. As many as 23 coastal creeks or saltwater estuaries, and innumerable salt and fresh lakes create a network of backwaters that drain rainwater flow and create a critical intertidal space.

Two main rivers of Goa, Mandovi and Zuari, drain 2,553 sq km, or 70% of Goa’s area. Heavy rainfall and hilly areas reaching right down to the coast make monsoon runoff drainage hydrology an important element of the ecosystem and settlement areas, which has to be taken into consideration to prevent flooding and disasters.

Traditional hydrology systems still extant in villages are a vast network of nullahs that both drain and percolate excess water. While seawater ingress along several estuaries has been contained through traditional embankments and a system of sluice gates. This has created vast areas of low-lying khazan lands that support two crops a year and also pisciculture.

Infrastructural projects have taken a toll on these systems, often rendering adjacent farms uncultivable. The state has begun to witness increased flooding due to disturbances to these systems and the authorities’ disdain for floodplain areas. Road construction, with elevated ramps through low-lying fields block water movement and drainage, creating stagnation, and ultimately, lead to disuse of fields and their conversion into commercial and urban plots.

Disregarding ecology

“Simple principles of ecology have not been considered [while developing infrastructure],” said Antonio Mascarenhas, a former member of Goa Coastal Zone Management Authority and a scientist formerly attached to National Institute of Oceanography.

An environmental campaign when the Konkan Railway was built in the 1990s resulted in many safeguards such as viaducts and culverts to ensure water flow. “Even so, 20 years later, one can see that the quality of vast tracts of farmland has been degraded due to water stagnation on one side of the track in some areas,” said Mascarenhas.

It seems similar mistakes are being made on the current road-building projects. In some cases, citizens have pushed back and petitioned courts, while the government has blamed NGOs for obstructing development.

People of Goa Velha village have protested the dumping of mud in a lake while building a service road. In January 2018, the Goa Coastal Zone Management Authority or GCZMA held a meeting to grant permission to fill an intertidal backwater area of Zuari River. Villagers in May 2018, along with their local lawmaker, raised concerns of flooding in the Cortalim area, which became a reality during flooding and heavy rains between August 4 and August 11 this year.

Further south, villagers in Loliem, Mashem and Galgibag in the Canacona sub-district approached the National Green Tribunal and the High Court against the building of coffer dams, embankments on the river bed and mud fillings at four places in the Mashem creek and Galgibag River for a highway bridge construction. Directed by the High Court to inspect the site, GCZMA said in March that earth fillings in the intertidal and mangrove areas are not permissible and recommended their removal “as early as possible.”

“The problem with cofferdams is that contractors don’t bother to clear them fully after the work is done,” said Mascarenhas. “From the time of the Konkan Railway construction, [coffer dam] mud left in the Talpona and Galgibag estuaries has got redistributed inside the estuary. Huge mangroves are growing there, and these two rivers are almost dying.”

Environmentalists also allege that environmental impact assessments are not properly conducted. “It’s a totally ad hoc development strategy and no proper environmental impact assessments are being done,” said Claude Alvares, director of Goa Foundation, an environmental advocacy group.

“The environmental impact assessment process has become a business,” said Mascarenhas. “I know organisations who have done thousands of environmental impact assessments and not one has gone against the client. One government department goes to another government department for an environmental impact assessment. How can that work?”

Nature pays back

The disregard for hydrology and environment has resulted in worsening natural disasters. This was most recently evident in the August flooding in Goa. The release of Tillari dam waters into the Tillari River flooded four villages in North Goa.

In many places, flooding and waterlogging was a result of major infrastructure work. For instance, the exit points to the third Mandovi bridge, call Atal Sethu, were a sea of water and the bridge had to be shut down for a while. The construction had taken place in reclaimed marshland and backwaters of Mandovi River.

“We’ve lost count of the number of times we protested to authorities over mud dumping in lakes and rivers for the [bypass] project,” said Karapurkar, the activist who has been raising awareness on the degradation of Sal River. “Nobody listens.”

This article first appeared on Mongabay.

Buy an annual Scroll Membership to support independent journalism and get special benefits.

Our journalism is for everyone. But you can get special privileges by buying an annual Scroll Membership. Sign up today!