“Writing about Vilayat Khan was like chasing a hologram,” writes author and journalist Namita Devidayal in her new book, The Sixth String of Vilayat Khan. Demystifying the dramatic life of one of classical Indian music’s greatest practitioners took a fair amount of detective work. Devidayal dug deep, travelling to the various corners of the world where he had lived and made music, and reading between the notes of his ragas to piece together a consistently compelling jigsaw puzzle.

The result is a book that is far from a conventional biography, one that is as mesmerising and memorable as the music that fills it. Reading it while listening to the accompanying playlist curated by Devidayal (on Amazon Music) is an overwhelming, immersive experience. We take a deep dive into his early years, stained with extraordinary pain and touched by incredible music, and witness, through Devidayal’s vivid portraits, the making of a musician, his rock star persona, why he went away to the hills and later, landed on American shores, and his many loves and the relationships that turned sour. The book offers a 360 degree view of the journey of classical music in his lifetime, while also being a delicate study of the human condition.

Devidayal spoke to Scroll.in about the peculiarities that made Vilayat Khan who he was, how she tackled a fragmented story and made it whole, crafting a poetic page turner, and the experience of narrating The Sixth String as an audio book with bits of music embedded in it, which she says is the first for a musical biography.

Tell us about what led to the book.

Vilayat Khan’s younger son, my friend Hidayat, kept chasing me to write a book about his father. I was going through a slightly low phase and decided that this would be an immersive project that would take me away from myself into a much wider beautiful space, so I finally agreed – but on the condition that this would be an independent book with no interference from any one, especially when it came to the salty bits. I also decided to do it because I had access to people who were very close to him – his sons, his senior-most student Arvind Parikh and the musicologist Deepak Raja who had analysed hours and hours of his recordings. This made a great difference given that there is very little archival material to draw from.

When did you start working on it and where did the book take you, geographically and metaphorically?

I started working on it about four years ago and kept on at it, in bits and pieces, whenever I was able, between my personal and professional commitments. It was a time when I was also going through a lot of personal transformation – of understanding the enigmatic and paradoxical human condition with compassion and without judgement – and I think that collaborated towards my understanding of him, for he was a man who had so many extraordinary and sometimes contradictory facets. It brought me closer to the idea that anarchy can coexist with harmony, and that pain sometimes leads to the greatest works of beauty. So I was truly inspired by his life and, of course, the depth of his music.

You discovered that everyone has a different memory of Vilayat Khan and a different take on the story. How did you then make sense of the fragments and piece them together?

I applied my journalistic skills to do some serious detective work into his life! I interviewed people who knew him closely as well as remotely – from his widow to his doggy vet to an American man who became obsessed with him. I listened to what they had to say, observed their body language about bits that were uncomfortable, learned to bypass the sycophantic praise. And I think I managed to put the jigsaw pieces together.

You call the book an impressionistic, fluid portrait, rather than a conventional biography. This has lent an intimate and evocative feel to the book. What kind of creative liberties did you take while writing it?

All along, I was very clear about having a certain integrity about my subject, so every thing I wrote came from somewhere – either a conversation with someone who knew him, or newspaper clippings or audio interviews. But because I wanted the book to have an easy readability to it, I took the liberty of converting something he may have said in an interview into a conversation, placed it inside a scene like in a movie. But even while I gave it colour and a backdrop, the words were his words.

Or, if I knew he loved a particular kind of fine velvet fabric, I took the liberty of dressing him in it for one of his concerts. Or, if I had heard him talk about an amazing moment he had with the king of Kabul, I recreated that scene after researching what it might have looked like. So it is a meticulously crafted narrative based entirely on fact, but with a lot of colour and texture added. I remember feeling slightly uncomfortable about taking such liberties, and speaking to Ramachandra Guha about it, and he put me on to that wonderful narrative biographer, Richard Holmes, who adopts a similar approach to his writing.

At the heart of this book is the paradox, like you say, of how anarchy coexists with harmony. Pain with beauty. Incredible highs after terrifying lows. Of intoxication and feeling dispirited. This is a motif in the lives of many creative artists. What were the peculiarities that defined Vilayat Khan and his music, that set him apart from other musicians?

The funny thing is that these paradoxes are inevitable in most individuals. In the creative ones, they merely get amplified. Some peculiarities that defined him – (but I can’t speak about other musicians, as I don’t know enough) – is that he remained a student and seeker until the day he died. There is that amazing story about how he chased down a young folk singer and begged him to teach him the boatman’s song he had heard his father sing so many decades ago. It speaks of a certain humility that is so important to remain creative. But conversely, he was also enormously egotistical and if someone crossed him, that was the end of the relationship and there was no looking back.

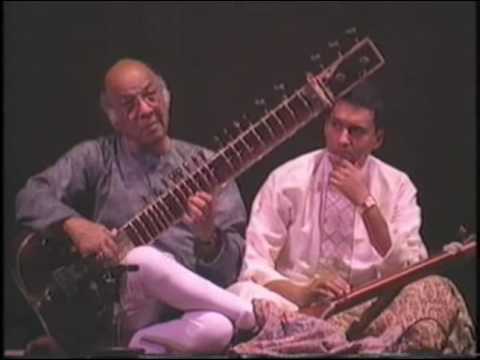

Vilayat Khan’s relationship with Ravi Shankar, his bête noir, is a recurring subject in the book. Did you find a discrepancy in the kind of rapport they actually shared and how it was made out to be by the people who surrounded them, such as their students and fans? How did you sift fact from fiction?

I believe they actually respected each other but that the rivalry would get spurred on by the students and fans. There is the legendary story about how Jasraj fanned a big public debate on who should be the more deserving recipient of the Bharat Ratna and, needless to say, the media lapped it up and gave it even more amplification. Having said that, I have heard that Vilayat Khan would often make tangential references to “populist artistes” during concerts and in his interviews, so obviously there was an undercurrent of rivalry. That is why I referred to them as “frenemies”. These are complicated spaces and artistes are enormously sensitive. With respect to fact and fiction, well, that was ongoing. But I definitely didn’t succumb to the obvious, and tempting, narrative of the rivalry as the spinal cord of his story – because it was not.

The book is full of colourful anecdotes that reveal Vilayat Khan beyond the music room, his penchant for good food, beautiful clothes, passion for owning and tinkering with fancy cars, debauchery…How did these facets feed off each other? Are there any stories that didn’t make it into the book that you could tell us here?

Vilayat Khan took equal interest in worldly things like cooking or playing cards as much as music. These were not separate silos in his life – he had a certain heightened sensibility which informed any thing he did. For instance, he believed that unless you had an appreciation for fine food, you could never have a refined sensibility in your music. He was able to extract beauty from everywhere – a painting, a carpet, a sunset, a conversation – and translate that into music. His ability to live life large is extraordinary. That is definitely a take-away for me! I am told he also had a tremendous sense of humour, was a prankster and a great mimic. What fun it must have been to be at the dinner table with him!

His deep flaws stand out even as you examine the making of a genius, the painful rifts in his family, his difficult and volatile relationships with his brother and sons in particular. How challenging was it to get his family and students to open up and to negotiate this territory while writing?

It was really very difficult and I would get mortified every time. I had to really win their trust and after the initial reservations, I could see each of them opening up and sharing intimate stories. With Hidayat it was much easier because he was vested in the book and is an open fellow who views his father with all his beauty and his flaws. I was well aware of the fractured relationship with Shujaat and am grateful for his honesty. He also read the book and said that it made him “laugh and cry and really laugh and really cry” which is the biggest endorsement I could have got. As for Imrat Khan, I was really nervous but knew I had to go all the way and meet him and hear about their childhood together. He was so gracious and I could see the pain and the hurt and the love all braided together in the way that happens with most family relationships.

Vilayat Khan’s story is all the more dramatic when you contextualise it the way you have, giving us a sweeping view of how the landscape and patronage of classical music in India changed in his lifetime, the evolution of the sitar in his hands, the politics of performing arts world and awards, and the ways in which classical music travelled overseas. All of this was closely tied to the cultivation of the public persona of Vilayat Khan, wasn’t it?

It was very important for me to zoom out during all the stages in his life to set the backdrop. For example, after the death of his father, his teachers came out of the new technology that had enabled so many musicians to expand their horizons – gramophone records. He relied on these extensively to really massage and enhance his own music. Also, the way in which travelling abroad played such a big role in validating him at a time when he was so disenchanted with the Indian scene is interesting. It speaks of the universal nature of music. How amazing that a Jewish New Yorker with zero background in Indian classical music became his most obsessive and sincere archivist.

It is an altogether more precious experience to read about Vilayat Khan composing the gorgeous Raga Sanjh Sarawali in the book while listening to him play it. Tell us about curating the playlist for Amazon Music?

I was so grateful to have the opportunity of curating a playlist for the book because it adds such a gorgeous dimension, allowing you to actually experience the magic. Rather than randomly scrolling YouTube videos, it is curated in relation to the narrative and includes very relevant pieces. The playlist doesn’t include merely his music, but a piece by his father and his grandfather, and also the famous duet with him and his brother which I dwell on in The Sixth String. It also has the background score for Jalsaghar and the song he composed for a Hindi film. All of these are referred to in the book, so it is a lovely addition to have alongside. Even more exciting is the fact that I have narrated the entire book as an audio book with bits of music embedded in it – which I believe is a first for any musical biography in the world.

This is a different book from your debut, The Music Room, which was a memoir. Yet, perhaps because classical music is the central motif in both, and they have a similar lyrical quality and a vivid narrative style that pulls you right into its heady world, bits from The Music Room kept floating into my head, even though I read it ten years ago. Did that happen to you too, while writing?

Thank you for your generous words! No, The Music Room did not come back to me because this was such a different book. The Sixth String is not a personal memoir. As for the style, there is a similar quality to it because I really believe in walking the reader into the story and bringing it alive, humanising it, adding the emotion, which is what distinguishes a good piece of music from a great piece. A reader recently gave me a very nice complement: He said, “You brought the ‘gayaki ang’ into your writing. You made the book sing.” That was what Vilayat Khan did to his sitar.

Finally, of all the places you visited to understand Vilayat Khan better, where did you feel most strongly connected to him and his music?

I think each of the places had a different energy. I felt it when I spent time with his late brother Imrat Khan in St Louis, Missourie and he played their famous duet for me and spoke about how he always played one step behind his “bhaiya” and he cried and praised him. The feelings were so palpable. I also felt it when I sat with Deepak Raja in his music room in Mumbai, listening to Vilayat Khan for hours, sharing the love and the admiration. I felt it when I sat with Hidayat in Princeton and he explained how his father saw the music and visualised the compositions. I felt it very potently when I visited Bhaini Sahib, a village in Ludhiana, where Vilayat Khan spent time as the musical guru of the Namdhari children. It was the place where his unconditional love for music came through. It has been quite an incredible journey, really.

Buy an annual Scroll Membership to support independent journalism and get special benefits.

Our journalism is for everyone. But you can get special privileges by buying an annual Scroll Membership. Sign up today!