The United Nations declared 1981 as the International Year of Disabled Persons. But for an exasperated Bombay citizen, it might as well have been The International Year of Disco.

Venting her ire in the op-ed page of Times of India, Sheila Parmanand wrote: “For although the handicapped have got their due (?) mention at seminars, ladies’ clubs, charitable institutions and Parliament, too, the zeal and fiery enthusiasm of the rich and middle classes, which could have worked wonders for the handicapped, have been dedicated to promoting the cause of ‘disco’.”

Yes, this was not a good time to be around if you happened to dislike disco. “One of the fastest-selling discs in India isn’t a soundtrack album,” said an article in Billboard magazine in July 1981. “It’s a slickly produced collection of tunes propelled by a catchy disco number…by a brother-sister duo with little professional experience.”

“Local youth talk in high tempo of how they danced to ‘Disco Deewane’,” reported Parmanand, “during the recent immersion processions at Ganesh Chaturthi.” Disco Dancer – and the dramatic rise of Bappi Lahiri – was still a year away, but disco seemed to be everywhere. Thus, Parmanand “was surprised but not shocked” when she received an invitation to a ‘Disco-Garba’. “What’s it going to be all about[?]” she wondered.

The question was rhetorical. “They…are more than aware of disco music,” she acknowledged, “thanks to Nazia Hassan and the plagiarisms of RD Burman. Besides, their modern young brothers-in-law from abroad have a collection of the latest disco cassettes, which are played repeatedly during their frequent picnics to the National Park and Vajreshwari. And to help them in their new venture, the brother of a famous music-director duo has come up with a ‘Disco-Dandiya-Geet’ on cassette.”

This “brother of a famous music-director duo” was Laxmichand Shah, known to most by his pet name, Babla. The second youngest among six children, he had a natural flair for rhythm, which saw him playing bongos and other percussion instruments from an early age for his brother Kalyanji Virji Shah at the latter’s stage shows.

Though mostly self-taught, Babla says he did receive some training in the dholak from the formidable Abdul Karim, the brother of pioneering percussionist and music director Ghulam Mohammed. “I sometimes also used to go to Cawas Lord [a former jazz drummer who worked as a percussionist in the film orchestras] on Sundays to learn notation,” he said.

It was with the hugely successful Jab Jab Phool Khile (1965) that Babla joined his brothers Kalyanji-Anandji. He initially worked as a session musician, but soon became their rhythm arranger. The very talented but unassuming Jaikumar Parte was the overall arranger while Frank Fernand, a trumpet player who arranged for music director Ravi, would conduct the orchestra. “If any additional brass arrangement was needed, Fernand would help,” Babla explained.

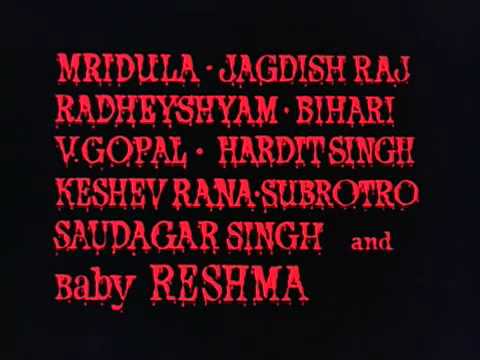

Parte and Fernand were in charge of the background music. “But often I would be asked to do the title music,” Babla claimed. “The title music of films like Johny Mera Naam, Kashmakash, Heera and Don was done by me.” He also composed some of Kalyanji-Anandji’s most iconic songs: Zindagi Ka Safar (Safar, 1970); Khaike Paan Banaraswala (Don, 1978); Pyar Zindagi Hai (Muqaddar Ka Sikandar (1978); Laila Main Laila (Qurbani, 1980).

While all this was happening, Babla had a parallel career as a bandleader. Babla And His Orchestra, which he started in 1963, performed at various dos, mostly playing film instrumentals. “We also did a special item called Around The World With Rhythm.” The musicians in his band were not drawn from the film orchestras. “They would stay in the band for a while and then move on.”

In 1964, Babla went abroad for the first time, when he accompanied the singer Mukesh on a tour to the West Indies and North America. It was a huge learning experience for him. “When I travelled abroad, I realised that one must also take care of other things, like the lighting, the sound, what you are wearing on stage,” he said.

Back home, these insights were assiduously adopted and integrated. “So, I bought psychedelic lights from London,” he said. “I started the trend of introducing the artiste using slide projection. I also designed how the band’s name would be written.”

The first professional show of Babla and His Orchestra was held at Mumbai’s Novelty theatre in 1970. By May 1972, they were already celebrating their 100th show. “This was at the Shanmukhananda,” he recalled. “A lot of people from the industry were there. Ashok Kumar and Dilip Kumar sang. Amitabh, whose Bombay to Goa had just released, danced.”

In 1974, the group went to Fiji, its first show outside India. On the way back, they stopped over in Singapore. There, Babla bought a MiniKorg, his first keyboard. “When I first brought it to the studio, I remember Kersi Lord asked me, ‘What is this toy you are carrying?’ A couple of days later, I saw he was playing with it!”

The MiniKorg was famously used in the classic Yeh Mera Dil (Don, 1978) – this, song, too, was composed by Babla – where it was played by Babla’s teenaged nephew Viju Shah. On the same song, Babla himself played an instrument called the lali, a traditional percussion instrument he had picked up in Fiji. “Every time I went abroad, I got something new,” he said. “I introduced many percussion instruments here, like the tumba, the timbales, which I later used for dandiya, and the octobans.”

The tour to Fiji was also significant for another reason. Accompanying them was a young singer named Kanchan. “She used to be a part of Ajanta Arts,” Babla said. (The Ajanta Arts Cultural Troupe, which had been formed by Sunil and Nargis Dutt, mostly did stage shows to entertain troops stationed at border outposts.) “She also sang in a band that belonged to one of my friends, Kishore Bham.”

Babla liked her voice and verve and recommended her to his composer brothers. Over the next decade, Kanchan sang in many of the duo’s films, giving hits like Tumko Mere Dil Ne (Rafoo Chakkar, 1975); Kya Khoob Lagti Ho (Dharmatma, 1975); and, of course, the chartbusting Laila Main Laila (Qurbani, 1980).

“For Laila Main Laila, I was the first to use rotodrums in India,” Babla said. “We recorded it at Western Outdoor with only about seven-eight musicians.” Not long after Qurbani’s release, Babla and Kanchan got married. By then, he had left the Kalyanji-Anandji fold. “We were getting very busy with shows,” he explained.

Until two decades ago, Navratri was a “women’s festival among Gujaratis”, wrote the academic Sonal Shukla in 1987. But by the early 1970s, young men had all but taken over the festival. “They collected funds, installed microphones and replaced women’s folksongs with tape-recorded music or hired bands…Navratri was gradually transformed into an extremely noisy and highly commercialised festival.”

While Babla may not have been the first to come up with the concept of disco dandiya, he came to be associated with it. The year 1981 saw the release of his now legendary Babla Presents Nonstop Disco Dandia, the first of what would become an annual affair. The album, says Babla, was actually targeted at the Gujarati diaspora crowd. “Those days, you did not have bands being invited from India during navratri,” he said. “So, this way, people could just play the record and dance along with the music.”

But at some point those involved with the album realised this had the potential to be much bigger. To promote the album in Mumbai, a mega event was organised at a drive-in theatre in the suburb of Bandra. “It was held a few days before Navratri,” Babla said. “There were almost 4,000 security personnel alone. The crowd was anything between 8000-10,000 people.” The success of the event, which he says was attended by several organisers, inspired many imitations.

Expectedly, disco dandiya also had its fair share of critics. “Five years ago, the Bombay Gujaratis started the ‘disco garba’ which sent shock waves in Gujarat,” wrote India Today in 1984. “The religious songs were replaced by garish new creations set to disco music…[T]he once pristine dance form has breathed its last.”

Four years later, writing in the same magazine, the journalist Salil Tripathi reported, “[T]he traditional Gujarati dandiya raas, which was already westernised with the introduction of disco, was transformed into laser dandiya where Gujjubhais and Gujjubens jived to the tunes of Babla and Lalit Sodha with illuminated dandiyas (sticks) till dawn.”

While others despaired, the decade marked a heady phase for Babla. In 1980, he released Babla’s Disco Sensation, an album that is today treasured by DJs and specialist vinyl collectors across the world. In 1981, the same year the first disco dandiya album came out, he also recorded Aratis in Disco. The immensely popular Yesterday Once More, which again featured instrumental cover versions of old film songs, released in 1982. Not long after, in the midst of the ghazal boom, he did an album featuring instrumental cover versions of popular ghazals sung by Pankaj Udhas and Anup Jalota. In between, he also found time to compose for a few films.

However, it is their work in the chutney genre that Babla and Kanchan will really be remembered for. Babla had heard the songs of the Trinidadian singer Sundar Popo (1943-2000), considered to be the father of chutney music, during his trips to the West Indies. “I used to like his songs but not the music treatment,” he said. So when he was approached to do an album in the genre, he grabbed the opportunity.

Following the success of Kaise Bani (1982) and Kuchh Gadbad Hai (1984), Babla and Kanchan toured extensively during the ’80s and ’90s, pulling in the crowds wherever they went. In the latter years, they were often accompanied onstage by their children, Nisha and Vaibhav. “My school was very cooperative,” Vaibhav Shah said. “if there was a tour coming up, they would let me take the exams early.”

Things slowed down after Kanchan’s untimely death in 2004 – she was only 54. “Today, I only do selected shows,” Babla said. While he continues to perform at dandiya events – he did a show in Antwerp in 2016 – his last trip to the West Indies was back in 2010. Babla speaks with great fondness about playing in front of large crowds in the Caribbean. “They love to dance, you know.”

He recalls an incident when it rained very heavily before a show. “The area that had been set out for dancing was very muddy. The audience was sitting in the balcony, nobody came out to dance. We, of course, could not cancel the show. So we started playing.” Slowly, people started leaving the safety of the enclosures and congregating on the wet dance floor. Soon, the area was packed with dancing bodies.

For Babla, it was always about the beat.

Buy an annual Scroll Membership to support independent journalism and get special benefits.

Our journalism is for everyone. But you can get special privileges by buying an annual Scroll Membership. Sign up today!