Photo credit: Jehangir Nicholson Art Foundation, CSMVS.

It is while viewing "Unpacking the Studio: Celebrating the Jehangir Sabavala Bequest", an exhibition on display at the Jehangir Nicholson Gallery at Mumbai’s Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sanghralaya, that one is able to comprehend Sabavala’s six-decade-long practice in context. The exhibition brings together Shirin Sabavala’s gift of her husband’s last paintings made between 2009 and 2011 along with a cornucopia of his photographs, sketchbooks, drawings, books and works of art he owned.

Photo credit: Jehangir Nicholson Art Foundation, CSMVS.

Curated by Sabavala’s essayist and biographer, the poet and cultural theorist Ranjit Hoskote, the exhibition unfolds in the form of a “visual and discursive essay” – as Hoskote prefers to describe it – in five chapters. These chapters are robustly drawn up: each segues seamlessly into the next, yet each is a distinctly immersive account by itself.

“I had curated Jehangir’s lifetime retrospective at the National Gallery of Modern Art, Bombay and Delhi, in 2005-2006,” explained Hoskote. “The present exhibition, I thought, would be an opportunity to craft the kind of choreographed journey through the intensities and loci of an artist’s life that the curator Massimiliano Gioni, following the artist Richard Hamilton, calls an ‘introspective’.”

Photo credit: Jehangir Nicholson Art Foundation, CSMVS.

A skeletal easel in a part of the gallery creates an impression of Sabavala’s studio. His fastidiousness about his work space can be seen in his well-preserved tools – paintbrushes, palette knives, spatulas, a well-worn set of wooden instruments from a geometry box, and a customised fiberglass palette.

Photo credit: Jehangir Nicholson Art Foundation, CSMVS.

Photo credit: Jehangir Nicholson Art Foundation, CSMVS.

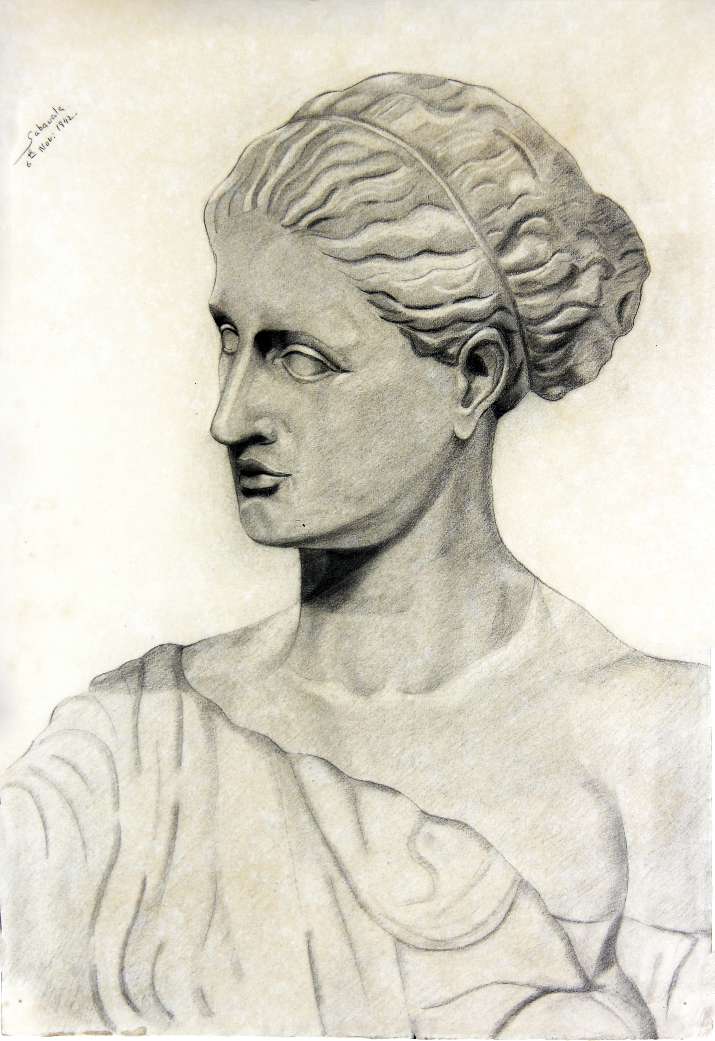

Sabavala’s preoccupation with perfection as a student in the 1940s is perceptible from the pages of his sketchbooks. The dimensions of each square of a grid used to make preliminary drawings are accurately measured to the last centimetre. His notes on colour gradations and tonal values – fraught with marginalia, calculations and even the exact time of the day when a painting was worked upon – are incredibly intricate. A scrapbook titled “My Physical Culture Album”, dating back to 1938, contains a bricolage of clippings from newspaper supplements and art journals that served as reference material for Sabavala so that he could perfect the contours of the human anatomy.

Bust of a woman. Photo credit: Jehangir Nicholson Art Foundation, CSMVS.

The exhibition, in all its capaciousness, is not just about Sabavala’s oeuvre and praxis.

“’Unpacking the Studio’ is also a project about the politics of cosmopolitanism,” said Hoskote. “When we consider this cultural phenomenon, we tend to emphasise the ‘cosmo-’, the world, the experience of being at home across borders. But we tend to overlook the ‘-politan’, which has to do with modes of being a citizen, belonging to an order of interpersonal relationships, having a certain relationship with an expanded community, an enlarged public sphere.”

The idea, Hoskote says, is to celebrate Sabavala’s refusal to sit quietly in some ethnic, linguistic or religiously defined nationalism, and his embracing of diverse cultural lineages. Having trained in London at the Heatherley School of Art, and later in Paris in an atelier context at Academie Julian, and as an apprentice under André Lhote, Sabavala was often typecast as an “escapist” by critics. His initial student years at Bombay’s JJ School of Art (1942-1945) and his body of work under the tutelage of Jagannath Murlidhar Ahivasi and Raghunath Dhopeshwarkar are often ignored.

“The charge of escapism is based on a banal notion that art should serve some prior ideological agenda that is wedded to social reform or realism,” said Hoskote.

The Eye. Photo credit: Jehangir Nicholson Art Foundation, CSMVS.

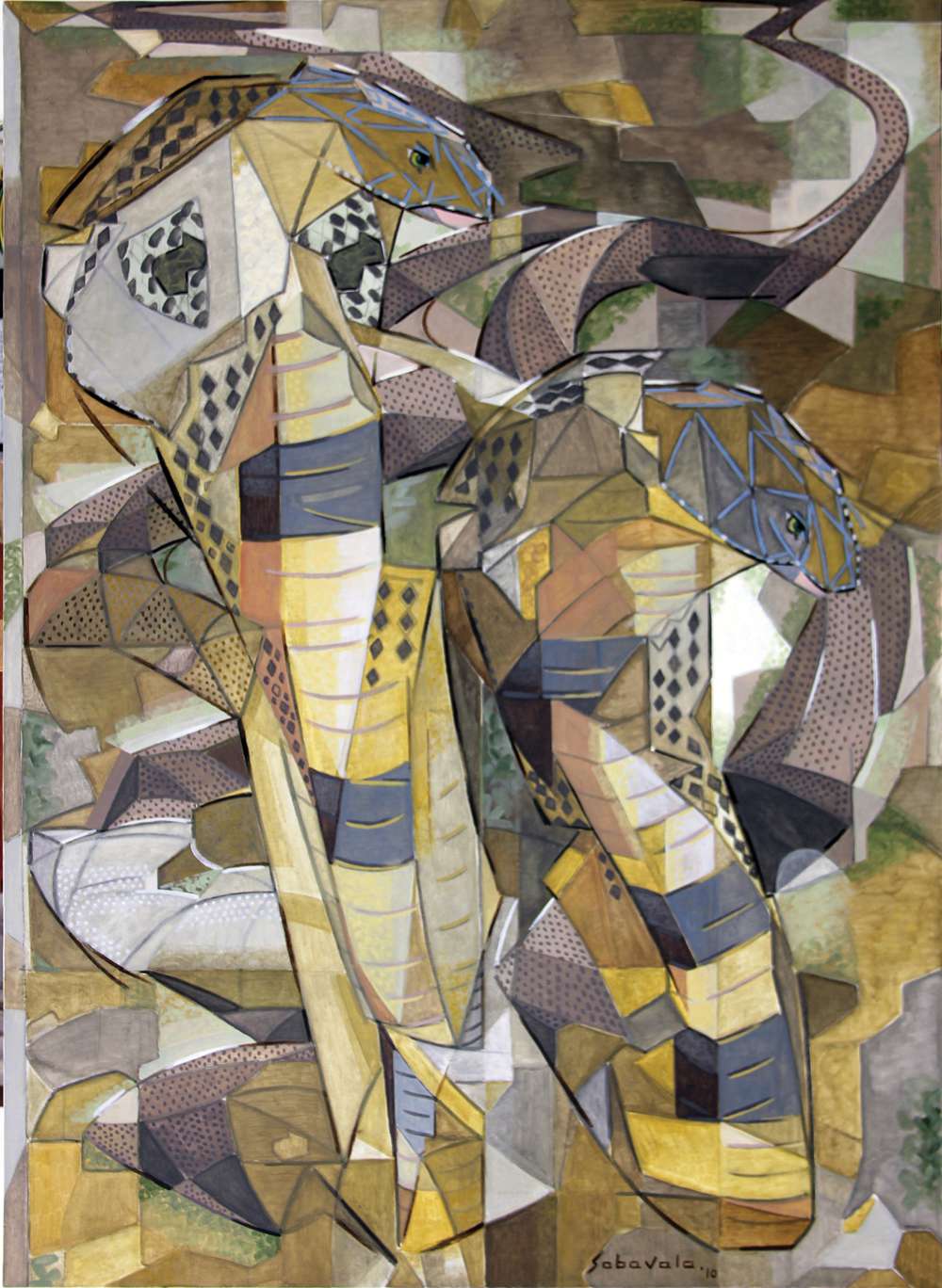

Another stringent label that Sabavala had to release himself from was that of a Cubist. “Sabavala very early left the classic Synthetic Cubism of his teacher André Lhote behind, and adapted Cubist possibilities to the challenges of the India to which he returned [from Paris] in 1951,” said Hoskote.

Sabavala didn’t want to be confined by a vapid style of painting. He began to reinvent himself as a painter, and by the early 1960s, the bold, sharp, explicit lines in his landscapes gradually began transforming into softer, intangible structures, fading into strokes of the brush that seek what is absent. His use of colours changed from vivid to austere; the faces he painted evaded the certitude of identity; and he started playing with light – developing an interest in its source, direction and eventually, its enigmatic outcome on the canvas. This metamorphosis is manifest in the works on display: The Seers I; The Inland Seas II; The Blue Seascape, to name a few, and also explains the title of the film, Colours of Absence, a phrase coined by the late poet Dom Moraes for Sabavala’s work.

The Cobras. Photo credit: Jehangir Nicholson Art Foundation, CSMVS.

The exhibition also provides momentum to the concept of bringing out objects from the reserve holdings of the museum – some of them painstakingly restored by the team at the Sanghralaya’s Museum Art Conservation Centre – and putting them on public display for the first time. “This was an occasion for abhijnana, a recognition of lost or eclipsed institutional memory, brought into a new conversation by the essay exhibition,” said Hoskote.

A number of works on display throw light on the panoply of artists Sabavala was influenced by and the art forms that shaped his practice – from Kabuki, a traditional Japanese theatre to a 19th century woodblock print by Kunisada Utagawa. These works do not serve as annotations, says Hoskote. They are part of the larger life of the individual artist, which is distributed across the gharana to which he belongs. Sabavala largely led a peripatetic life and often sought retreat in verdant Matheran, Mahabaleshwar, and Gholvad in Maharashtra, which inspired some of his works.

Through archival photographs and elevation plans, the exhibition orients the viewer with the act of reading the built environment of Bombay within its historical framework, cultural institutions, patronage and artists’ friendships and alliances.

The scene in Matheran. Photo credit: Jehangir Nicholson Art Foundation, CSMVS.

While the meticulousness with which Sabavala worked is nearly unmistakable, it perhaps reverberates in the exacting attention to detail that Hoskote lends to his curation of the show – a profound interiority, a methodical yet introspective approach, almost akin to an archivist.

"Unpacking the Studio: Celebrating the Jehangir Sabavala Bequest" is on display at the Jehangir Nicholson Art Foundation in Mumbai's Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sanghralaya until December 31.

Limited-time offer: Big stories, small price. Keep independent media alive. Become a Scroll member today!

Our journalism is for everyone. But you can get special privileges by buying an annual Scroll Membership. Sign up today!