One of my favourite places as a child, which we frequented every week, was a tiny lending library in Chennai, with steel shelves reaching up to the ceiling. I would look up, straining my neck, picking out my next adventure. Two men sat at the door, with several long notebooks placed before them. I would watch with fascination and bubbling excitement as they wrote down the names of books I had picked and sent them my way.

In Ahmedabad, where I teach, my students do not have the means to venture to MJ library, which is the nearest library, and can be reached only after crossing the Sabarmati. Nor do they have the will to go to the British library, which is the only other alternative. Both these libraries are intimidating at first, and the children’s sections lie tucked away on another floor, or behind all the other sections, a secret land for the lucky children with the keys to the kingdom.

The sheer romance

I was one such child. I grew up reading volumes and creating movies from books in my mind. Of course it was imperative that my class have a library. As the books began to come, donated by extraordinary people, I took a suitcase full of books to class every day. It began to get heavier. So, I bought our first trunk for four hundred rupees from the Sunday market at Riverfront.

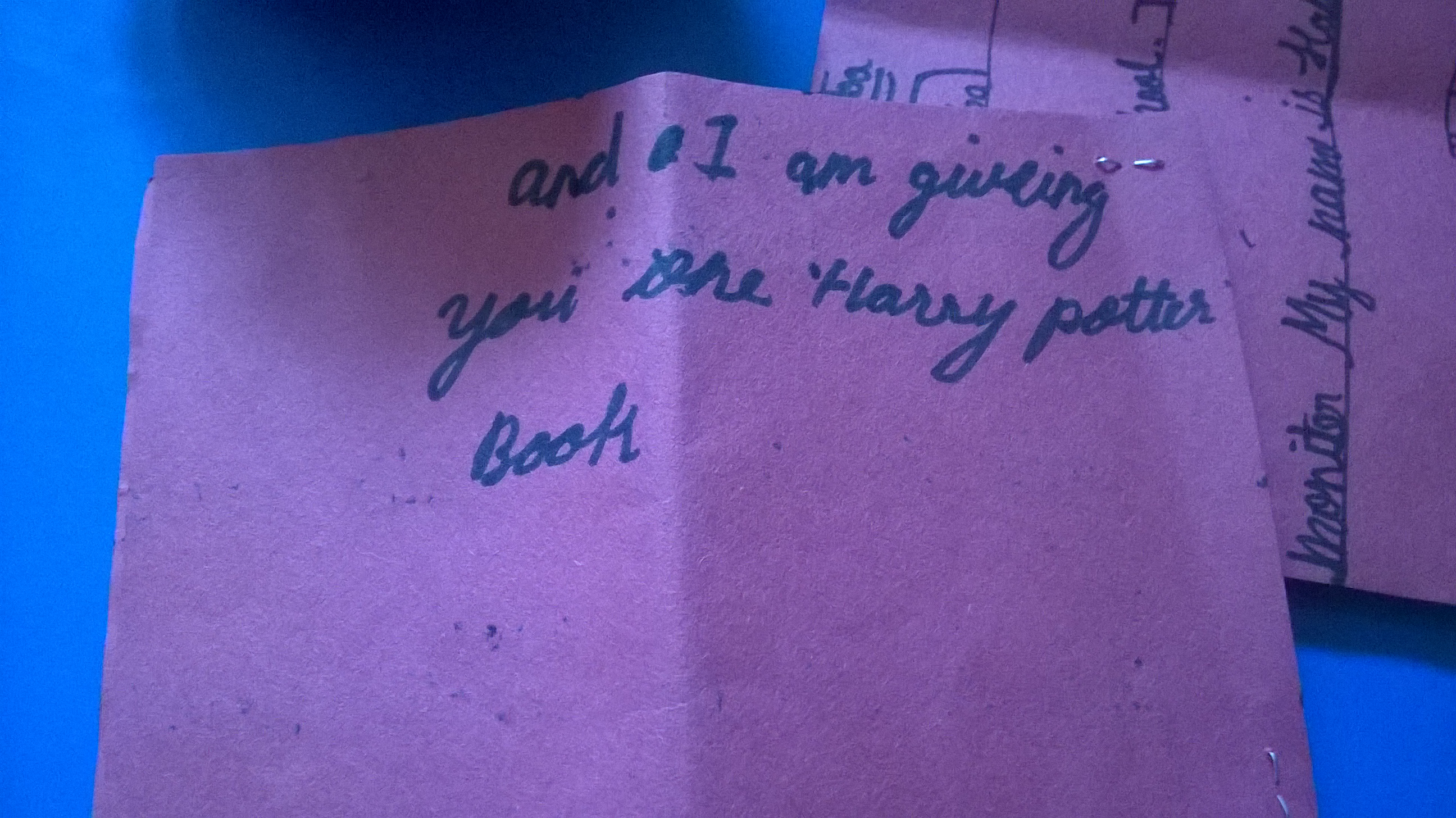

I lugged the green trunk to class. Everybody wanted to know what it was. It came to be called: the library trunk. The next trunk came in silver, decorated with thank you letters from another school. You see, they had lost their library over the summer to theft. So our librarians sent 20 books to their aid.

I can unabashedly tell you that library time is my favourite time of the day. I read my book, they read theirs. I write in my journal, they write in theirs. Some flip pages, some read aloud tracing with their fingers, some will come and recount to me a story they just read.

They read in Gujarati, they love it, they want more, more and more. They want to show their parents and siblings. They love Urdu picture books! Then, they read in English. Oh, if I put French books in there, they would teach it to themselves.

When I leave my eight- and nine-year-olds to substitute or teach in a higher class, I see anxious faces that want to read and play. But I see something else too. Embarrassment. Somehow, by this time, it is no longer innocent and cool to read. Reading any book at all, not unlike being academically inclined, or pious, is now mocked openly, and coveted in secret.

No access

My experience with adults is downright acidic. A school principal was appalled that we would allow children to touch books worth tens of thousands of rupees. There is uncanny bitterness associated with glossy, colourful books. They are untouchable. Yes, I said it.

Children do not deserve such expensive books, seems to be the frustrating consensus. It is all too familiar to hear parents and teachers say, “It’s enough if you read your textbooks”. Libraries set up in schools, big and small, government and private, go to dust over decades of disuse under the pretext of lack of management, under the pretext of preserving the books.

We are not in dire need for more books in this country. CBT, NBT, Pratham, Tulika and others all publish excellent books and sell them for the price of a family pack of chips. Books are donated and sold to second-hand sellers every day. Our country even imports seconds from as far away as the UK, in mint condition. We buy books by the kilo for children in our homes, from markets in Bombay, Bangalore and Chennai. Did we not make Daryaganj in Delhi famous for old books?

How ironic then, that the very books we display behind inaccessible glass slowly build bitterness that starts the dangerous, completely unnecessary cycle of withholding books from the next generation of yearning children. Neil Gaiman said in an interview: “I think the most important thing is a space that’s safe, and safe in all sorts of ways. Safe to work, safe to think. And [a space that has] librarians, because the librarians are the people who are curating the thing.”

Let me do the unfashionable thing of stating the obvious: our curators don’t love reading.

But you do. So do the magical thing of volunteering as a librarian, even part time, in schools and libraries. We need librarians who approach our children’s libraries as crazy adults who love picture books would.

What is one thing all of us adults can do to “get” children to read? Tell them the books are theirs. Tell them the library belongs to them. Let them run it. They will hold the books close to their chests and guard them as you guard yours. They will stop their friends from scribbling. They will stack books neatly, over and over and over, only to admire their handiwork. They will inventory them; they will manage borrows and returns. They will skim, they will ogle, they will giggle, and then, they will read to be transported. They will read to understand.

Rohini Manyam Seshasayee always drools over libraries and bookstores. She is currently a Teach for India fellow.

In Ahmedabad, where I teach, my students do not have the means to venture to MJ library, which is the nearest library, and can be reached only after crossing the Sabarmati. Nor do they have the will to go to the British library, which is the only other alternative. Both these libraries are intimidating at first, and the children’s sections lie tucked away on another floor, or behind all the other sections, a secret land for the lucky children with the keys to the kingdom.

The sheer romance

I was one such child. I grew up reading volumes and creating movies from books in my mind. Of course it was imperative that my class have a library. As the books began to come, donated by extraordinary people, I took a suitcase full of books to class every day. It began to get heavier. So, I bought our first trunk for four hundred rupees from the Sunday market at Riverfront.

I lugged the green trunk to class. Everybody wanted to know what it was. It came to be called: the library trunk. The next trunk came in silver, decorated with thank you letters from another school. You see, they had lost their library over the summer to theft. So our librarians sent 20 books to their aid.

I can unabashedly tell you that library time is my favourite time of the day. I read my book, they read theirs. I write in my journal, they write in theirs. Some flip pages, some read aloud tracing with their fingers, some will come and recount to me a story they just read.

They read in Gujarati, they love it, they want more, more and more. They want to show their parents and siblings. They love Urdu picture books! Then, they read in English. Oh, if I put French books in there, they would teach it to themselves.

When I leave my eight- and nine-year-olds to substitute or teach in a higher class, I see anxious faces that want to read and play. But I see something else too. Embarrassment. Somehow, by this time, it is no longer innocent and cool to read. Reading any book at all, not unlike being academically inclined, or pious, is now mocked openly, and coveted in secret.

No access

My experience with adults is downright acidic. A school principal was appalled that we would allow children to touch books worth tens of thousands of rupees. There is uncanny bitterness associated with glossy, colourful books. They are untouchable. Yes, I said it.

Children do not deserve such expensive books, seems to be the frustrating consensus. It is all too familiar to hear parents and teachers say, “It’s enough if you read your textbooks”. Libraries set up in schools, big and small, government and private, go to dust over decades of disuse under the pretext of lack of management, under the pretext of preserving the books.

We are not in dire need for more books in this country. CBT, NBT, Pratham, Tulika and others all publish excellent books and sell them for the price of a family pack of chips. Books are donated and sold to second-hand sellers every day. Our country even imports seconds from as far away as the UK, in mint condition. We buy books by the kilo for children in our homes, from markets in Bombay, Bangalore and Chennai. Did we not make Daryaganj in Delhi famous for old books?

How ironic then, that the very books we display behind inaccessible glass slowly build bitterness that starts the dangerous, completely unnecessary cycle of withholding books from the next generation of yearning children. Neil Gaiman said in an interview: “I think the most important thing is a space that’s safe, and safe in all sorts of ways. Safe to work, safe to think. And [a space that has] librarians, because the librarians are the people who are curating the thing.”

Let me do the unfashionable thing of stating the obvious: our curators don’t love reading.

But you do. So do the magical thing of volunteering as a librarian, even part time, in schools and libraries. We need librarians who approach our children’s libraries as crazy adults who love picture books would.

What is one thing all of us adults can do to “get” children to read? Tell them the books are theirs. Tell them the library belongs to them. Let them run it. They will hold the books close to their chests and guard them as you guard yours. They will stop their friends from scribbling. They will stack books neatly, over and over and over, only to admire their handiwork. They will inventory them; they will manage borrows and returns. They will skim, they will ogle, they will giggle, and then, they will read to be transported. They will read to understand.

Rohini Manyam Seshasayee always drools over libraries and bookstores. She is currently a Teach for India fellow.

Scroll has produced award-winning journalism despite violent threats, falling ad revenues and rising costs. Support our work. Become a member today.

In these volatile times, Scroll remains steadfastly courageous, nuanced and comprehensive. Become a Scroll Member and support our award-winning reportage, commentary and culture writing.