In his 50 years in Ludhiana, Harbans Singh Bhanwer has seen it all.

Around 1965, when he began making machine parts in Punjab’s biggest industrial centre, the town was booming. The Green Revolution was underway, and Ludhiana provided a large part of the engineering underpinning for that boom.

Some units made farm implements, while others processed locally-grown cotton into yarn and clothes. Companies like Bhanwer’s Craft Tools built the machines these factories ran on. Others operated in manufacturing sectors like cycles, sewing machines and auto parts.

In those days, says Bhanwer, Ludhiana was known as the “Manchester of India”.

The city, and the now ageing patriarch of a clan that has mostly relocated to Canada, grew together. They saw growth ebb due to bank nationalisation during the Emergency years of the early 1970s, and again in the early 1980s due to militancy. Each time, India’s Manchester dusted itself off and got back to the serious business of growing.

By 1991, Ludhiana was exporting to countries in the Gulf, and Europe. By 2002-’03, Bhanwer’s Craft Tools was selling its products – bearings, castings, hydraulic systems and motors – not only across India but also in the United Arab Emirates and Italy.

Over the last decade, however, Craft Tools has seen a steady slide. By 2005, it had lost its international clients. By 2012-’13, it had slipped into freefall. That year, the company’s turnover was Rs 85 lakh. The next year, it fell to Rs 55 lakh. In 2014-’15, it was Rs 37 lakh. This year, says Bhanwer, “About Rs 27-28 lakh” till date.

During the same period, Ludhiana has mirrored this slump. Its biggest companies are moving away. Its smaller units are shutting down.

Take its cotton industry. According to a senior official at Nahar Industrial Enterprises, which manufactures cotton yarn, garments and woollens, the company now makes 40% of its yarn and denim in Madhya Pradesh. Similarly, he said, referring to other industry majors, “All of Vardhman’s expansion is now outside Punjab. And 50% of Trident’s capacity is now in Madhya Pradesh.”

A similar slowdown can be seen in another Ludhiana mainstay – cycles. The town is home to some of the top national cycle brands, like Hero and Avon. These companies too are expanding not in Punjab, but elsewhere. And between this relocation of the big units and the decision to source more from China, the smaller units, which made a living supplying parts to the big brands, have been hammered.

Things have got especially bad in the last four years, says Amarjit Singh, proprietor of Bhumi Solutions, a real estate company located in Ludhiana’s industrial area. “Only about 40% of the companies here are surviving. Another 30% have sublet their premises to other businesses. And about 30% have shut down.”

None of this is unique to Ludhiana. Over the last ten years – and especially since 2010 – Punjab has seen a process of deindustrialisation.

In Jalandhar, the sports goods industry, which used to export footballs around the world till 20 years ago, has yielded ground to cheaper Chinese products. In the steel town of Mandi Gobindgarh, says DK Mehta, office secretary of the Induction Furnace Association of North India, “We had 300 furnaces three years ago. That is now down to 150, and even those are running at 50% capacity.”

In the holy town of Amritsar, the textile industry has shuttered.

Hasrat Ali, 26, works in a small unit making cycle parts in Ludhiana. His pay is Rs 6,000. Over the last four years, the town is seeing numbers of migrant labour fall – another indicator of a slowing economy.

The erosion of industry is one of the major crises facing Punjab. As the number of units shrinks, the state government will struggle to increase its revenues; as revenues dip, Punjab’s already constrained ability to deliver services like education, healthcare and, as the previous story noted, extension services to farmers will decline further.

Industry in a vice

At a time when the Central government is attempting to project India as a manufacturing destination, why are places like Ludhiana, Jalandhar and Mandi Gobindgarh – some of India’s biggest industrial clusters – shutting down rather than growing?

The first reason is this: Rising cost of operation, which makes Punjab’s industries non-competitive in comparison with other Indian states, and with China.

Take Jalandhar, once a global hub of sports goods manufacture. Seventy per cent of what it made was inflatables, the industry term for volleyballs, basketballs, footballs, beachballs and the like. In the run-up to the 1990 FIFA World Cup, says Vipan Mahajan, secretary general of the Sports Goods Manufacturers & Exporters Association, “India and Pakistan supplied footballs to the world.”

The town also manufactured cricket kits, hockey sticks and indoor games. “Jalandhar had a monopoly on boxing gloves – we used to sell them globally.”

That has changed now, with the entry of cheap Chinese-made footballs. “We produce at $2 and they, at $1.50. How do we compete? Today, 90% of the market is theirs.”

The only part of the inflatables market that Jalandhar still operates in, Mahajan says, is synthetic balls for rugby and football – about 10% of the global market.

This has triggered a reorganisation of the industry. Earlier, companies used to get orders for, say, racquets, and outsource production to 5,000 or so smaller units. Now, as bigger companies shut down or start selling imported wares, as is the case with gym equipment, these small feeder units have shuttered. I met one man, Mahajan says, who used to make racquets. “He now sells moolis (radish).”

The cycle industry mirrors this sorry story. Big brands such as Hero Cycles used to make some parts of a cycle, such as the frame, handlebar, fork, wheel rims and chainwheels, and outsource the rest to smaller units. Here too, says Harinderpal Singh, a managing partner in Birdi Cycle Industries, which makes cycle components like freewheels and chains, a similar set of processes has played out. About eight years ago, Chinese imports began coming in as fully-built cycles and components. As a result, not only have the bigger companies moved a part of their production to other states, they have also switched to Chinese components.

“The chain we make here cost Rs 28 about five, six years ago,” Singh said. “At that time, a Chinese chain cost Rs 16-17. Cycle makers therefore began importing components from China. With that, half the cycle industry here went sick. The pedal-manufacturing business shut down. Similarly, steel ball-bearings, spokes, chainwheels, all of them shut down.”

An article published in the Economic and Political Weekly’s October 24, 2015, issue explains some of these outcomes. Titled “Import Liberalisation and Premature Deindustrialisation in India”, the article says import liberalisation has damaged India’s manufacturing sector instead of boosting it through exposure to international competition. It flags the rapid rise in net imports in several industries to question whether imports are displacing domestic production.

The declining allure of Punjab

As cheaper imports came in, companies began looking for ways to survive. At this point, four factors converged.

First, with margins under pressure, companies began to question whether Punjab was an optimal location. In an age of globalisation, says PD Sharma, president of Punjab’s Apex Chamber of Commerce and Industry, the state has a structural disadvantage.

“Exports and imports are very critical. Nearness to ports is advantageous. In that sense, Punjab has a problem. To manufacture here, you have to transport raw material all the way from the nearest port. And to transport finished goods from here, you have to pay a heavy amount for freight.”

Second, even as these issues began to be felt, rival states were offering tax holidays and other sops to lure industry.

Take textiles: According to the Nahar official, the industry began shifting out when states like Himachal Pradesh offered tax holidays. In the last 4-5 years, more states have entered the fray, notably Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat and Maharashtra.

“They are all cotton-growing states,” the official pointed out. “And they give various incentives – cheap land, capital subsidy, power benefits, cheap labour. Plus, these states are also consumption centres, and have easier access to ports. Export ke liye zyada beneficial ho gaya.”

For similar reasons, some of Punjab’s steel units have relocated closer to cities like Raipur, which are closer to coal mines.

Punjab shoots itself in the foot

With its once-robust manufacturing industry struggling to compete with rivals elsewhere, Punjab had only one logical option: to reduce the cost of doing business. Instead, to their chagrin, companies found their power and tax rates climbing even higher.

Some of the charges are farcical. Punjab, for instance, charges octroi and – wait for it – a cow cess on power. The latter is about 1.4% of the power bill. Apart from this, there is also an electricity duty, and an infrastructure cess, levied on power bills.

“Bijli is very costly,” said Bhanwer of Craft Tools. “Rs 8 a unit, when other states are charging Rs 5. And then there is VAT, it is 6.05% in Punjab – the highest in all India, while it is 3-3.5% in other states. This makes our diesel and petrol costlier too.”

In contrast, “states like Himachal, Jharkhand and Uttarakhand are offering 10-year tax holidays, power at Rs 5, no infrastructure tax and no inspector checking. Land is cheaper there as well”. If Craft Tools were to relocate, says Bhanwer, its margins would rise by 10-15%.

Consider VAT. A letter by the Mohali Industries Association says LED manufacturers in Punjab pay a VAT of 13.5%. In contrast, their rivals in neighbouring states pay 5.5%.

There are many reasons why Punjab’s power and tax rates are higher than competing states. The state gives free power to its farmers. However, it has to pay the state power utility the full price of that power. The cash-strapped state doesn’t have enough money to meet the bill. So, says Padamjit Singh, head of the Punjab State Electricity Board’s Engineers Association, it adds duties and levies to power bills and asks the power utility to retain what comes in against those heads, adjusting it against the state’s dues.

“The idea of levying duties and cesses was to use the money for power development,” said the engineer. “Instead, it is being used to fund a subsidy. Industry doesn’t even have the comfort that what it is being skinned for will ultimately flow back to it.”

Complicating matters is the fact that the bulk of Punjab’s industrial base comprises relatively cash-strapped small and medium enterprises, on whom falls the brunt of subsidies to farmers.

Some of this has to do with the political construct in the state. “Politics here is controlled by the Jat Sikhs, and they are agriculturalists,” said Pramod Kumar, director of Chandigarh’s Institute for Development and Communication. “They are largely unmindful of industry.” Kumar had studied state assembly debates between 1960 and 2010, and found that “just 10% of their time was spent on non-agricultural issues”.

As the state’s need for revenue has grown, it has hiked rates and taxes repeatedly to the point where industry finds it more sensible to move out – this, despite the additional investments of time and money a greenfield project demands.

There is also predatory extraction, says Sucha Singh Gill, director-general of the Centre for Research in Rural and Industrial Development in Chandigarh. Punjab-based companies talk about the political pressure to share profits with the ruling Akali Dal. One businessman, who wanted to set up an atta factory, said the party asked him for a 3-4% chunk of his turnover. “My margins are 10-15%. 3-4% was too high,” he said.

As competition intensified and larger clients moved away, Punjab’s manufacturing units found themselves staring into an abyss. The resulting desperation has resulted in multiple outcomes. Some companies diverted bank loans to land deals in the hope of getting better returns.

Till about three and a half years ago, Punjab was seeing a realty boom. Land was doubling in value every six months to two years. Companies therefore used bank loans as working capital for buying land. Then the land market collapsed. Now, says Amarjit Singh of Bhumi Solutions, “khud ka business chalaney ke liye paisa nahin hain (There is no money for running their original business).”

Anger is rising against the state government, especially after it hosted its latest investment summit where it promised power at Rs 5 to industries setting up shop here. “Arre, pehle hamey to bacha lo (They should save us first),” said one industrialist this reporter spoke to.

Why SMEs feel the most pain

An official of Ludhiana’s District Industries Centre, who did not want to be named, has been watching the various processes unfold. While the bigger companies can move out of the state, it is the smaller ones, he pointed out, “jo pis rahi hain (they are being ground down)”.

There are many reasons. For one, both the Centre and the state have failed to prepare small and medium enterprises for import liberalisation. Mohali is an example.

"We wanted to set up an industry centre for which money would come from the Centre", says Kanwaljit Singh Mahan, a former president of the Mohali Industries Association. It would have had a design centre, a tool room, a National Accreditation Board for Testing and Calibration Laboratories-approved lab. He faced disinterest from both the Centre and the state. Eventually, the Centre sanctioned the money – but the state is yet to finish the paperwork. “Kamse kam expedite to kar do (They should at least expedite the work).”

"By the time the centre comes up", Singh says, "China will have moved farther ahead". Visit the cycle cluster in Ludhiana, and you hear a similar refrain about lack of research and development.

In the absence of R&D, even 24 years after liberalisation, the industrial clusters of Punjab continue to function through jugaad, improvisation. Very few industries have managed to grow into megaliths like Hero, Avon or Nahar; most have remained small and, as the squeeze continues, it is they that pay the heaviest price.

The District Industries Centre official says that of the 20,000 companies in Ludhiana, 45% have less than Rs 25 lakh invested in plant and machinery. Another 35% have invested between 25 lakh and Rs 5 crore. Medium and large (defined as anything above Rs 10 crore) companies account for just 20% of all companies in the cluster.

Not only does this mean that these small to medium companies cannot invest in R&D on their own, they also cannot afford to relocate. Meanwhile, for the big companies, explains the Nahar official, expansion can easily become the precursor to an exit. “As the machines in Ludhiana get older, we will have to decide whether to replace them or not.”

This will accelerate the decline. Over the years, small units had sprung up around the big companies, making a living by feeding inputs to them – be it machine parts, packing material, whatever. “When we expand elsewhere, the expansion plans of these units will stop,” the Nahar official points out. “They will have to relocate too.”

Relocation is however not easy for small companies, as it means investing in acquiring land and building afresh. Even if the smaller companies can afford that, they have to then wait for new customers.

Maan Singh, 68, runs a machine-tooling factory with a net worth of Rs 10 lakh. The day I met him, he and his son were building a power press. “Companies with money can relocate,” he said. “They can buy land elsewhere and start up again. But we cannot do that. Hum wahan jayengey to grahak kyon aayega? Sab grahak yahan aatey hain. Yahaan 200-500 factories hain (Why will our customers follow us to the new place? All of them come to Ludhiana. Most machine tooling factories are here).”

Today he makes one machine a month where he once used to make four, each selling for anywhere between Rs 1.5 lakh to Rs 2 lakh. “We don’t have labour. We are not able to pay more than Rs 6,000. Khud kaam kartey hain to nikalta hai (We can make ends meet only if we ourselves do the work).”

It’s a downward spiral, with the very real risk that things could go horribly wrong – as happened with Rajinder Singh.

Till seven years or so ago, Singh used to make pedals for bicycles. The inflow of cheap Chinese imports caused his business to collapse. When I met him, he was pushing a cycle through Ludhiana’s industrial area. It was laden with myriad repurposed bottles, from two-litre soft drink bottles to more nondescript smaller ones, all filled with Phenyl.

It is a tough life for someone in his mid-fifties. The combined weight of the bottles, he said, would be about 100 litres. Selling them nets him about Rs 300-400 in a day. “I work from 7.30 to 2,” he said. “I cannot work longer than that.”

Around 1965, when he began making machine parts in Punjab’s biggest industrial centre, the town was booming. The Green Revolution was underway, and Ludhiana provided a large part of the engineering underpinning for that boom.

Some units made farm implements, while others processed locally-grown cotton into yarn and clothes. Companies like Bhanwer’s Craft Tools built the machines these factories ran on. Others operated in manufacturing sectors like cycles, sewing machines and auto parts.

In those days, says Bhanwer, Ludhiana was known as the “Manchester of India”.

The city, and the now ageing patriarch of a clan that has mostly relocated to Canada, grew together. They saw growth ebb due to bank nationalisation during the Emergency years of the early 1970s, and again in the early 1980s due to militancy. Each time, India’s Manchester dusted itself off and got back to the serious business of growing.

By 1991, Ludhiana was exporting to countries in the Gulf, and Europe. By 2002-’03, Bhanwer’s Craft Tools was selling its products – bearings, castings, hydraulic systems and motors – not only across India but also in the United Arab Emirates and Italy.

Over the last decade, however, Craft Tools has seen a steady slide. By 2005, it had lost its international clients. By 2012-’13, it had slipped into freefall. That year, the company’s turnover was Rs 85 lakh. The next year, it fell to Rs 55 lakh. In 2014-’15, it was Rs 37 lakh. This year, says Bhanwer, “About Rs 27-28 lakh” till date.

During the same period, Ludhiana has mirrored this slump. Its biggest companies are moving away. Its smaller units are shutting down.

Take its cotton industry. According to a senior official at Nahar Industrial Enterprises, which manufactures cotton yarn, garments and woollens, the company now makes 40% of its yarn and denim in Madhya Pradesh. Similarly, he said, referring to other industry majors, “All of Vardhman’s expansion is now outside Punjab. And 50% of Trident’s capacity is now in Madhya Pradesh.”

A similar slowdown can be seen in another Ludhiana mainstay – cycles. The town is home to some of the top national cycle brands, like Hero and Avon. These companies too are expanding not in Punjab, but elsewhere. And between this relocation of the big units and the decision to source more from China, the smaller units, which made a living supplying parts to the big brands, have been hammered.

Things have got especially bad in the last four years, says Amarjit Singh, proprietor of Bhumi Solutions, a real estate company located in Ludhiana’s industrial area. “Only about 40% of the companies here are surviving. Another 30% have sublet their premises to other businesses. And about 30% have shut down.”

None of this is unique to Ludhiana. Over the last ten years – and especially since 2010 – Punjab has seen a process of deindustrialisation.

In Jalandhar, the sports goods industry, which used to export footballs around the world till 20 years ago, has yielded ground to cheaper Chinese products. In the steel town of Mandi Gobindgarh, says DK Mehta, office secretary of the Induction Furnace Association of North India, “We had 300 furnaces three years ago. That is now down to 150, and even those are running at 50% capacity.”

In the holy town of Amritsar, the textile industry has shuttered.

Hasrat Ali, 26, works in a small unit making cycle parts in Ludhiana. His pay is Rs 6,000. Over the last four years, the town is seeing numbers of migrant labour fall – another indicator of a slowing economy.

The erosion of industry is one of the major crises facing Punjab. As the number of units shrinks, the state government will struggle to increase its revenues; as revenues dip, Punjab’s already constrained ability to deliver services like education, healthcare and, as the previous story noted, extension services to farmers will decline further.

Industry in a vice

At a time when the Central government is attempting to project India as a manufacturing destination, why are places like Ludhiana, Jalandhar and Mandi Gobindgarh – some of India’s biggest industrial clusters – shutting down rather than growing?

The first reason is this: Rising cost of operation, which makes Punjab’s industries non-competitive in comparison with other Indian states, and with China.

Take Jalandhar, once a global hub of sports goods manufacture. Seventy per cent of what it made was inflatables, the industry term for volleyballs, basketballs, footballs, beachballs and the like. In the run-up to the 1990 FIFA World Cup, says Vipan Mahajan, secretary general of the Sports Goods Manufacturers & Exporters Association, “India and Pakistan supplied footballs to the world.”

The town also manufactured cricket kits, hockey sticks and indoor games. “Jalandhar had a monopoly on boxing gloves – we used to sell them globally.”

That has changed now, with the entry of cheap Chinese-made footballs. “We produce at $2 and they, at $1.50. How do we compete? Today, 90% of the market is theirs.”

Vipan Mahajan, secretary general of the Jalandhar Sports Goods Association. “We produce [footballs] at $2. China at $1.50.” All photos: M Rajshekhar

The only part of the inflatables market that Jalandhar still operates in, Mahajan says, is synthetic balls for rugby and football – about 10% of the global market.

This has triggered a reorganisation of the industry. Earlier, companies used to get orders for, say, racquets, and outsource production to 5,000 or so smaller units. Now, as bigger companies shut down or start selling imported wares, as is the case with gym equipment, these small feeder units have shuttered. I met one man, Mahajan says, who used to make racquets. “He now sells moolis (radish).”

The cycle industry mirrors this sorry story. Big brands such as Hero Cycles used to make some parts of a cycle, such as the frame, handlebar, fork, wheel rims and chainwheels, and outsource the rest to smaller units. Here too, says Harinderpal Singh, a managing partner in Birdi Cycle Industries, which makes cycle components like freewheels and chains, a similar set of processes has played out. About eight years ago, Chinese imports began coming in as fully-built cycles and components. As a result, not only have the bigger companies moved a part of their production to other states, they have also switched to Chinese components.

“The chain we make here cost Rs 28 about five, six years ago,” Singh said. “At that time, a Chinese chain cost Rs 16-17. Cycle makers therefore began importing components from China. With that, half the cycle industry here went sick. The pedal-manufacturing business shut down. Similarly, steel ball-bearings, spokes, chainwheels, all of them shut down.”

An article published in the Economic and Political Weekly’s October 24, 2015, issue explains some of these outcomes. Titled “Import Liberalisation and Premature Deindustrialisation in India”, the article says import liberalisation has damaged India’s manufacturing sector instead of boosting it through exposure to international competition. It flags the rapid rise in net imports in several industries to question whether imports are displacing domestic production.

The declining allure of Punjab

As cheaper imports came in, companies began looking for ways to survive. At this point, four factors converged.

First, with margins under pressure, companies began to question whether Punjab was an optimal location. In an age of globalisation, says PD Sharma, president of Punjab’s Apex Chamber of Commerce and Industry, the state has a structural disadvantage.

“Exports and imports are very critical. Nearness to ports is advantageous. In that sense, Punjab has a problem. To manufacture here, you have to transport raw material all the way from the nearest port. And to transport finished goods from here, you have to pay a heavy amount for freight.”

Second, even as these issues began to be felt, rival states were offering tax holidays and other sops to lure industry.

Take textiles: According to the Nahar official, the industry began shifting out when states like Himachal Pradesh offered tax holidays. In the last 4-5 years, more states have entered the fray, notably Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat and Maharashtra.

“They are all cotton-growing states,” the official pointed out. “And they give various incentives – cheap land, capital subsidy, power benefits, cheap labour. Plus, these states are also consumption centres, and have easier access to ports. Export ke liye zyada beneficial ho gaya.”

For similar reasons, some of Punjab’s steel units have relocated closer to cities like Raipur, which are closer to coal mines.

Punjab shoots itself in the foot

With its once-robust manufacturing industry struggling to compete with rivals elsewhere, Punjab had only one logical option: to reduce the cost of doing business. Instead, to their chagrin, companies found their power and tax rates climbing even higher.

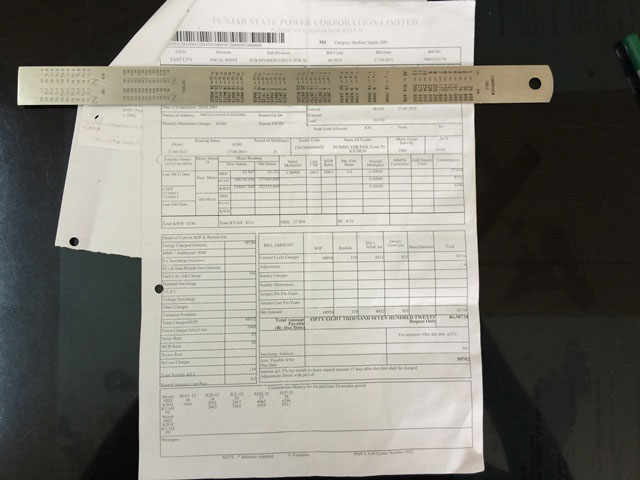

Some of the charges are farcical. Punjab, for instance, charges octroi and – wait for it – a cow cess on power. The latter is about 1.4% of the power bill. Apart from this, there is also an electricity duty, and an infrastructure cess, levied on power bills.

Take a closer look at the bit in the middle. Punjab charges octroi and cow cess on its power bills.

“Bijli is very costly,” said Bhanwer of Craft Tools. “Rs 8 a unit, when other states are charging Rs 5. And then there is VAT, it is 6.05% in Punjab – the highest in all India, while it is 3-3.5% in other states. This makes our diesel and petrol costlier too.”

In contrast, “states like Himachal, Jharkhand and Uttarakhand are offering 10-year tax holidays, power at Rs 5, no infrastructure tax and no inspector checking. Land is cheaper there as well”. If Craft Tools were to relocate, says Bhanwer, its margins would rise by 10-15%.

Consider VAT. A letter by the Mohali Industries Association says LED manufacturers in Punjab pay a VAT of 13.5%. In contrast, their rivals in neighbouring states pay 5.5%.

There are many reasons why Punjab’s power and tax rates are higher than competing states. The state gives free power to its farmers. However, it has to pay the state power utility the full price of that power. The cash-strapped state doesn’t have enough money to meet the bill. So, says Padamjit Singh, head of the Punjab State Electricity Board’s Engineers Association, it adds duties and levies to power bills and asks the power utility to retain what comes in against those heads, adjusting it against the state’s dues.

“The idea of levying duties and cesses was to use the money for power development,” said the engineer. “Instead, it is being used to fund a subsidy. Industry doesn’t even have the comfort that what it is being skinned for will ultimately flow back to it.”

Complicating matters is the fact that the bulk of Punjab’s industrial base comprises relatively cash-strapped small and medium enterprises, on whom falls the brunt of subsidies to farmers.

Some of this has to do with the political construct in the state. “Politics here is controlled by the Jat Sikhs, and they are agriculturalists,” said Pramod Kumar, director of Chandigarh’s Institute for Development and Communication. “They are largely unmindful of industry.” Kumar had studied state assembly debates between 1960 and 2010, and found that “just 10% of their time was spent on non-agricultural issues”.

As the state’s need for revenue has grown, it has hiked rates and taxes repeatedly to the point where industry finds it more sensible to move out – this, despite the additional investments of time and money a greenfield project demands.

There is also predatory extraction, says Sucha Singh Gill, director-general of the Centre for Research in Rural and Industrial Development in Chandigarh. Punjab-based companies talk about the political pressure to share profits with the ruling Akali Dal. One businessman, who wanted to set up an atta factory, said the party asked him for a 3-4% chunk of his turnover. “My margins are 10-15%. 3-4% was too high,” he said.

As competition intensified and larger clients moved away, Punjab’s manufacturing units found themselves staring into an abyss. The resulting desperation has resulted in multiple outcomes. Some companies diverted bank loans to land deals in the hope of getting better returns.

Till about three and a half years ago, Punjab was seeing a realty boom. Land was doubling in value every six months to two years. Companies therefore used bank loans as working capital for buying land. Then the land market collapsed. Now, says Amarjit Singh of Bhumi Solutions, “khud ka business chalaney ke liye paisa nahin hain (There is no money for running their original business).”

Anger is rising against the state government, especially after it hosted its latest investment summit where it promised power at Rs 5 to industries setting up shop here. “Arre, pehle hamey to bacha lo (They should save us first),” said one industrialist this reporter spoke to.

Why SMEs feel the most pain

An official of Ludhiana’s District Industries Centre, who did not want to be named, has been watching the various processes unfold. While the bigger companies can move out of the state, it is the smaller ones, he pointed out, “jo pis rahi hain (they are being ground down)”.

There are many reasons. For one, both the Centre and the state have failed to prepare small and medium enterprises for import liberalisation. Mohali is an example.

"We wanted to set up an industry centre for which money would come from the Centre", says Kanwaljit Singh Mahan, a former president of the Mohali Industries Association. It would have had a design centre, a tool room, a National Accreditation Board for Testing and Calibration Laboratories-approved lab. He faced disinterest from both the Centre and the state. Eventually, the Centre sanctioned the money – but the state is yet to finish the paperwork. “Kamse kam expedite to kar do (They should at least expedite the work).”

"By the time the centre comes up", Singh says, "China will have moved farther ahead". Visit the cycle cluster in Ludhiana, and you hear a similar refrain about lack of research and development.

In the absence of R&D, even 24 years after liberalisation, the industrial clusters of Punjab continue to function through jugaad, improvisation. Very few industries have managed to grow into megaliths like Hero, Avon or Nahar; most have remained small and, as the squeeze continues, it is they that pay the heaviest price.

The District Industries Centre official says that of the 20,000 companies in Ludhiana, 45% have less than Rs 25 lakh invested in plant and machinery. Another 35% have invested between 25 lakh and Rs 5 crore. Medium and large (defined as anything above Rs 10 crore) companies account for just 20% of all companies in the cluster.

Not only does this mean that these small to medium companies cannot invest in R&D on their own, they also cannot afford to relocate. Meanwhile, for the big companies, explains the Nahar official, expansion can easily become the precursor to an exit. “As the machines in Ludhiana get older, we will have to decide whether to replace them or not.”

This will accelerate the decline. Over the years, small units had sprung up around the big companies, making a living by feeding inputs to them – be it machine parts, packing material, whatever. “When we expand elsewhere, the expansion plans of these units will stop,” the Nahar official points out. “They will have to relocate too.”

Relocation is however not easy for small companies, as it means investing in acquiring land and building afresh. Even if the smaller companies can afford that, they have to then wait for new customers.

Maan Singh, 68, runs a machine-tooling factory with a net worth of Rs 10 lakh. The day I met him, he and his son were building a power press. “Companies with money can relocate,” he said. “They can buy land elsewhere and start up again. But we cannot do that. Hum wahan jayengey to grahak kyon aayega? Sab grahak yahan aatey hain. Yahaan 200-500 factories hain (Why will our customers follow us to the new place? All of them come to Ludhiana. Most machine tooling factories are here).”

Today he makes one machine a month where he once used to make four, each selling for anywhere between Rs 1.5 lakh to Rs 2 lakh. “We don’t have labour. We are not able to pay more than Rs 6,000. Khud kaam kartey hain to nikalta hai (We can make ends meet only if we ourselves do the work).”

It’s a downward spiral, with the very real risk that things could go horribly wrong – as happened with Rajinder Singh.

Rajinder Singh on his morning round, selling phenyl to industries in Ludhiana.

Till seven years or so ago, Singh used to make pedals for bicycles. The inflow of cheap Chinese imports caused his business to collapse. When I met him, he was pushing a cycle through Ludhiana’s industrial area. It was laden with myriad repurposed bottles, from two-litre soft drink bottles to more nondescript smaller ones, all filled with Phenyl.

It is a tough life for someone in his mid-fifties. The combined weight of the bottles, he said, would be about 100 litres. Selling them nets him about Rs 300-400 in a day. “I work from 7.30 to 2,” he said. “I cannot work longer than that.”

Buy an annual Scroll Membership to support independent journalism and get special benefits.

Our journalism is for everyone. But you can get special privileges by buying an annual Scroll Membership. Sign up today!