The professor will not forget 2015 easily.

A scientist at Ludhiana’s Punjab Agriculture University, he has been studying cotton for 15 years. But what he saw this year was entirely unfamiliar.

It started with the rains. Punjab saw downpours during the normally dry months of March and April. It rained in June as well – a month when temperatures should have touched 47 degrees, with hot summer winds (the famous loo) gusting across the state.

Instead, the temperature stayed below 40 degrees on most days that month. On the days it did rise, said the scientist, who spoke to Scroll on the condition of anonymity, it did not cross 43 degrees.

More climatic strangeness followed. It barely rained in the traditional monsoon months of July and August. The first three weeks of September stayed dry as well, followed by heavy rains towards the end of the month.

The aberrant weather patterns catalysed a boom in whitefly – an insect that sucks sap from plants during its nymphal stage. And this triggered, among other things, a political crisis in Punjab.

Typically, whiteflies emerge around March and are active till winter sets in. Most years, they are a minor pest preying on most crops, their numbers kept in check by the loo and then the rains. This year, however, the skies stayed overcast but the earth saw little rain; temperatures stayed relatively low and humidity relatively high, creating conditions where whitefly numbers began rising earlier than usual – in June.

Crawling out of their eggs, the nymphs encountered a cotton crop that was more vulnerable than usual. The rains in March and April had delayed the winter harvest – the wheat crop took longer to ripen. This in turn delayed the sowing of cotton. “Due to the late sowing, the crop was just 1.5 months old when the Whiteflies came,” says the scientist. “Normally, it is about 3 months old, and therefore more robust.”

It was a perfect storm. Whiteflies live for about 24-30 days – a quicksilver lifespan in course of which eggs hatch into nymphs, nymphs change into pupas, and pupas become adult whiteflies which mate, lay eggs on crop leaves and die. This year, with favourable conditions lasting longer during the cotton crop, Punjab saw an explosion in their numbers.

The plants were swamped. As the nymphs sucked out the sap, the plants sickened.

What happened next was inevitable. Anywhere between two-fifths to two-thirds of Punjab’s cotton crop was damaged. By mid-October, about 15 farmers had killed themselves. A farmers’ agitation, demanding compensation from the state, began.

Pesticides failed to control the plague, giving rise to speculation that they were fake. The director of Punjab’s agriculture department and several pesticide dealers were duly arrested.

The unrest was building when reports began to proliferate about copies of the Guru Granth Sahib being desecrated in several parts of the Punjab. Public attention swung away from the failed cotton crop – and in the process, the state squandered a chance to understand why whitefly erupted this year.

Make no mistake – fake pesticides are not the primary reason the crop failed.

Start with the rains.

Why were the rains abnormal?

From his office in the Indian Meteorological Department’s red-brick building in Chandigarh’s Sector 39, Surender Paul, a director, has been witnessing large changes in the weather patterns over Punjab.

Punjab gets almost all its rainfall during the monsoon months. Over the last 15 years, said Paul, the state has “seen a decline in mean precipitation between June and September”. In the last ten years, it has seen six “meteorological droughts”, the term for when rainfall is at least 25% below normal.

Paul sees other changes. Historically, rains used to reach the state around June 30. They now arrive five days earlier. Their departure has been delayed as well. “The norm is September 30. But now, winds start blowing towards the south seven-eight days later than before.”

Rainfall is also getting concentrated across time and space. This year, most of the rainfall over Punjab occurred in just 10 days. “This is one of the patterns we are seeing – a few days of concentrated rainfall,” said Paul. At the same time, the state is seeing greater local variations in rain. This year, for instance, only six out of the 22 districts in the state got normal rainfall.

Paul’s work suggests these changes are manifestations of a new interaction between mid-latitude westerlies and India’s monsoons.

It’s like this: The monsoon originates to the south-west of India, over the Arabian Sea, and then moves north till the Himalayas, curving along India’s eastern coast before moving towards the low pressure area that develops over central India due to the summer heat.

As for the westerlies, these blow at a greater distance from the equator, starting from about 32 N (Latitude) – say, the northern tip of Punjab.

However, over the last ten years, the westerlies have been swinging farther south. This trend, said Paul, is seen mostly in the monsoon and winter months. In the last four or five years, they have reached as far south as 25 North – that is, the northern reaches of Madhya Pradesh. In the process, India is seeing greater interaction between the westerlies and the monsoon. “In the last ten years, the influence of extra-tropical weather has increased," he said. "We have seen as many as 40 instances of western disturbances affecting the monsoons this year.”

It’s not yet clear why the westerlies are swinging south in recent years. What is incontrovertible, however, is that the monsoonal trough – the low pressure area which attracts monsoon clouds – is coming to depend on the interplay between the westerlies and the monsoon winds. The collision of the two, says Paul, results in the formation of a large cloud mass and an abrupt, short-lived but intense cloudburst. That is what India has seen this year in Jammu and Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand and Rajasthan.

Elsewhere, rainfall tends to be low. With the monsoon clouds weakened, more rain falls on places that are more conducive for rainfall – like lakes and forests. The moisture they release into the air, says Paul, encourages precipitation.

All of this bodes ill for Punjab. The state’s industrial belt releases emissions that reduce the quantum of moisture in the air. Further, the state has no dense forest cover – less than 4% of the state is forested. States to its north and east have far higher forest cover.

The collapse of extension work

The change in rainfall patterns combined with another factor to create the crisis in Punjab’s cotton fields this year.

During the heyday of the green revolution in the 1970s and '80s, Punjab had a large bureaucracy that transmitted agricultural knowhow to farmers – chief agricultural officers and gram sewaks in each district, doing what was called agricultural extension. There were also kisan melas at the block and district levels that disseminated knowhow about agriculture and technology – information on new crops, seeds, fertilisers, implements and pesticides – to farmers through camps and lectures.

The system does not work any more. There has been a 50%-60% reduction in the number of extension workers, scientists say. The remaining staff is often deputed for other work – like conducting local elections.

One fallout of the collapse of extension work? It hamstrung attempts to fight off whitefly.

Take Balwana village, about 12 kilometres from the agricultural town of Abohar. Here Jagdish Kumar, a young man in his thirties who runs a shop near the village gurudwara that sells agricultural inputs (fertilisers and pesticides), had a window seat to what happened once the whiteflies arrived.

First, the crisis was spotted late. “Farmers responded only when the whiteflies started flying over their field," he said. "That is when they asked for medicine, saying, ‘Mujhe spray de do ki kal ko mujhe whitefly dikhai nahin de.’" Give me a medicine which will make sure there is not a single whitefly over my field tomorrow.

There are several problems with such a process, Kumar said. First, whitefly is at its most dangerous as a nymph, which is when it sucks away at the sap and enfeebles the plant. “The whitefly stage is not so harmful," he said. "All that will happen is the insect will lay the next generation of eggs.”

Second, spraying the flies will not help if it is not coordinated. “All the flies have to do is move to an adjoining field where spraying is not yet underway,” he noted.

Third, the lack of information about the emergent weather patterns meant that the farmers did not spray their fields for a long time. As the Met department noticed, the weather stayed overcast with minor drizzles. This made farmers reluctant to spray “Companies tell farmers that fields should stay dry for four-six hours after spraying," Jagdish said. "And the spray is costly – Rs 1,800/litre. Since farmers were never sure when it would rain, they deferred spraying.”

So the eggs grew undisturbed into mites, with concentrations per leaf much higher than before; the plants weakened and their leaves turned black. Which is when, Kumar said, desperate farmers began looking for medicines – “sprays, synthetics, anything”.

Take Hazara Ram of Balwana. The farmer, now in his sixties, sprayed four different pesticides in a bid to control his whitefly outbreak. None of them worked. His harvest was just 80 kilos from two acres, which netted him no more than Rs 4,000 – against which, he spent Rs 5,000 on pesticides alone.

In this part of India, it is the kharif crop – usually a cash crop like basmati or cotton – that introduces variability into farmers’ annual income. The winter crop, usually sold to the government at fixed rates, is more of a safety net. Like Hazara Ram, Sukhdev Singhji, a resident of Balwana village near Abohar, will not make any money on his cotton crop this year. He will make money only if wheat (kanak, in Punjabi) does well: “Kanak bachave to bachave.”

There is another issue here: Given that whitefly go through four stages – egg, nymph, pupa and adult – how did farmers like Ram know the stage of infection and therefore the appropriate medicines to spray?

They went by what agricultural traders or company agents – whose job is to sell pesticides – told them.

The rise of new 'knowhow'

As Punjab’s extension machinery weakened, other actors stepped into the void – such as companies that sell fertiliser and pesticides. Said the Punjab Agriculture University scientist, “Their agents usually visit villages 15 days before the time of application. If the pesticide doesn’t work, they start working in another village. As it is, they are not even agri-graduates.”

Most of them are very young, said Sukhdev Singhji – “Navey munde. Unhey khud hi nahin pata honda.”

Another entrant into this informational vacuum is the adatiya, the agricultural trader. As an article in the November 7, 2015, issue of the Economic & Political Weekly, titled “Commission Agent System: Significance in Contemporary Agricultural Economy of Punjab”, notes: “They [adatiyas] have become the exploitative alternative for supply of credit, farm and domestic inputs as well as sale of produce. Not only do they provide credit for purchasing essential articles, but also push the farmers to purchase the same from the shops they, or their friends, own.”

One reason for their rise is the worsening economics of agriculture in Punjab.

Take cotton: It is mainly grown in the southern reaches of Punjab, in the Malwa region. On the whole, this is the poorest of the three regions of the state, and the one that sees the most farmer suicides.

Bt Cotton came here in 2004, in response to the American bollworm attacks that started in 1997. Sukhpal Singh, head of Punjab Agricultural University’s Department of Economics and Sociology, points out that since then, though farmer incomes have risen, their debt has not come down.

There are several reasons for this, Singh said. While Bt Cotton was resistant to bollworm, after about seven or eight years of normalcy, attacks from secondary pests started. At the same time, input costs began rising faster than output prices. “It was partly globalisation. Subsidy on input prices was reduced. Diesel and machinery and seeds got costlier. At the same time, international cotton prices fell.”

This is a story that is playing out all across Punjab. As the cost of agriculture rises and its profitability falls, Punjab’s farmers are being pushed into debt – 89% of all farming households are in debt, according to this EPW paper. They borrow from the adatiyas. When the harvest comes in, they give the crop to the adatiyas who sell it, recover the loan, and give the balance to the farmers.

And so, when whiteflys came, most farmers turned to the traders seeking pesticides. The EPW paper estimates that 15.01% of pesticides in Punjab (across all crops) are now supplied from the shops of commission agents, and another 80% are procured from the shops owned by people connected to these agents. They, says the paper, issue “a “slip” to farmers for obtaining items from their “owned or connected shops”.

This further compromised farmers’ efforts against whiteflies. There was now the added risk that the traders (who are not farmers) might recommend the wrong pesticide, or one with a greater margin, or that farmers might buy cheaper pesticides to keep their debt low.

Agreed the scientist, “Extension work has collapsed. Paisa nahin hain. Udhaar lena hain. Sasti kaun si hain?”

Singhji, for instance, sprayed a fungicide while trying to take on whitefly.

That won’t work, said Jagdish, the young shop-owner of Balwana, pointing out that farmers sprayed unthinkingly. “Decide kuch nahin kiya, jo mila woh daal diya," he said. They sprayed whatever they could get.

Other farmers underestimated the whitefly crisis and either sprayed the right medicine too late, or used a milder pesticide than they should have. Matters were further complicated by perennial factors like fake pesticides and batch variations. “I see a farmer’s plot after spraying and if there is no change a day later, I send that batch of spray back,” said Jagdish.

That is the arithmetic of this moment. It’s telling that farmers held off spraying as long as the skies stayed overcast – it shows that farmers’ knowhow is static in a world that is changing fast. The state needs to work on mitigation and adaptation. And for that, it needs to prepare its farmers better.

“Our outreach has to be strengthened,” said Surinder Paul of the Met department. “The information is there. But not all farmers are getting it.”

Failing that, the state will only see the turmoil in its farmlands increase.

This is the last part in a series on how climate change in affecting India.

A scientist at Ludhiana’s Punjab Agriculture University, he has been studying cotton for 15 years. But what he saw this year was entirely unfamiliar.

It started with the rains. Punjab saw downpours during the normally dry months of March and April. It rained in June as well – a month when temperatures should have touched 47 degrees, with hot summer winds (the famous loo) gusting across the state.

Instead, the temperature stayed below 40 degrees on most days that month. On the days it did rise, said the scientist, who spoke to Scroll on the condition of anonymity, it did not cross 43 degrees.

More climatic strangeness followed. It barely rained in the traditional monsoon months of July and August. The first three weeks of September stayed dry as well, followed by heavy rains towards the end of the month.

The aberrant weather patterns catalysed a boom in whitefly – an insect that sucks sap from plants during its nymphal stage. And this triggered, among other things, a political crisis in Punjab.

Typically, whiteflies emerge around March and are active till winter sets in. Most years, they are a minor pest preying on most crops, their numbers kept in check by the loo and then the rains. This year, however, the skies stayed overcast but the earth saw little rain; temperatures stayed relatively low and humidity relatively high, creating conditions where whitefly numbers began rising earlier than usual – in June.

Crawling out of their eggs, the nymphs encountered a cotton crop that was more vulnerable than usual. The rains in March and April had delayed the winter harvest – the wheat crop took longer to ripen. This in turn delayed the sowing of cotton. “Due to the late sowing, the crop was just 1.5 months old when the Whiteflies came,” says the scientist. “Normally, it is about 3 months old, and therefore more robust.”

It was a perfect storm. Whiteflies live for about 24-30 days – a quicksilver lifespan in course of which eggs hatch into nymphs, nymphs change into pupas, and pupas become adult whiteflies which mate, lay eggs on crop leaves and die. This year, with favourable conditions lasting longer during the cotton crop, Punjab saw an explosion in their numbers.

The plants were swamped. As the nymphs sucked out the sap, the plants sickened.

What happened next was inevitable. Anywhere between two-fifths to two-thirds of Punjab’s cotton crop was damaged. By mid-October, about 15 farmers had killed themselves. A farmers’ agitation, demanding compensation from the state, began.

Pesticides failed to control the plague, giving rise to speculation that they were fake. The director of Punjab’s agriculture department and several pesticide dealers were duly arrested.

The unrest was building when reports began to proliferate about copies of the Guru Granth Sahib being desecrated in several parts of the Punjab. Public attention swung away from the failed cotton crop – and in the process, the state squandered a chance to understand why whitefly erupted this year.

Make no mistake – fake pesticides are not the primary reason the crop failed.

Start with the rains.

Why were the rains abnormal?

From his office in the Indian Meteorological Department’s red-brick building in Chandigarh’s Sector 39, Surender Paul, a director, has been witnessing large changes in the weather patterns over Punjab.

Punjab gets almost all its rainfall during the monsoon months. Over the last 15 years, said Paul, the state has “seen a decline in mean precipitation between June and September”. In the last ten years, it has seen six “meteorological droughts”, the term for when rainfall is at least 25% below normal.

Paul sees other changes. Historically, rains used to reach the state around June 30. They now arrive five days earlier. Their departure has been delayed as well. “The norm is September 30. But now, winds start blowing towards the south seven-eight days later than before.”

Rainfall is also getting concentrated across time and space. This year, most of the rainfall over Punjab occurred in just 10 days. “This is one of the patterns we are seeing – a few days of concentrated rainfall,” said Paul. At the same time, the state is seeing greater local variations in rain. This year, for instance, only six out of the 22 districts in the state got normal rainfall.

Paul’s work suggests these changes are manifestations of a new interaction between mid-latitude westerlies and India’s monsoons.

It’s like this: The monsoon originates to the south-west of India, over the Arabian Sea, and then moves north till the Himalayas, curving along India’s eastern coast before moving towards the low pressure area that develops over central India due to the summer heat.

As for the westerlies, these blow at a greater distance from the equator, starting from about 32 N (Latitude) – say, the northern tip of Punjab.

However, over the last ten years, the westerlies have been swinging farther south. This trend, said Paul, is seen mostly in the monsoon and winter months. In the last four or five years, they have reached as far south as 25 North – that is, the northern reaches of Madhya Pradesh. In the process, India is seeing greater interaction between the westerlies and the monsoon. “In the last ten years, the influence of extra-tropical weather has increased," he said. "We have seen as many as 40 instances of western disturbances affecting the monsoons this year.”

It’s not yet clear why the westerlies are swinging south in recent years. What is incontrovertible, however, is that the monsoonal trough – the low pressure area which attracts monsoon clouds – is coming to depend on the interplay between the westerlies and the monsoon winds. The collision of the two, says Paul, results in the formation of a large cloud mass and an abrupt, short-lived but intense cloudburst. That is what India has seen this year in Jammu and Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand and Rajasthan.

Elsewhere, rainfall tends to be low. With the monsoon clouds weakened, more rain falls on places that are more conducive for rainfall – like lakes and forests. The moisture they release into the air, says Paul, encourages precipitation.

All of this bodes ill for Punjab. The state’s industrial belt releases emissions that reduce the quantum of moisture in the air. Further, the state has no dense forest cover – less than 4% of the state is forested. States to its north and east have far higher forest cover.

The collapse of extension work

The change in rainfall patterns combined with another factor to create the crisis in Punjab’s cotton fields this year.

During the heyday of the green revolution in the 1970s and '80s, Punjab had a large bureaucracy that transmitted agricultural knowhow to farmers – chief agricultural officers and gram sewaks in each district, doing what was called agricultural extension. There were also kisan melas at the block and district levels that disseminated knowhow about agriculture and technology – information on new crops, seeds, fertilisers, implements and pesticides – to farmers through camps and lectures.

The system does not work any more. There has been a 50%-60% reduction in the number of extension workers, scientists say. The remaining staff is often deputed for other work – like conducting local elections.

One fallout of the collapse of extension work? It hamstrung attempts to fight off whitefly.

Take Balwana village, about 12 kilometres from the agricultural town of Abohar. Here Jagdish Kumar, a young man in his thirties who runs a shop near the village gurudwara that sells agricultural inputs (fertilisers and pesticides), had a window seat to what happened once the whiteflies arrived.

First, the crisis was spotted late. “Farmers responded only when the whiteflies started flying over their field," he said. "That is when they asked for medicine, saying, ‘Mujhe spray de do ki kal ko mujhe whitefly dikhai nahin de.’" Give me a medicine which will make sure there is not a single whitefly over my field tomorrow.

There are several problems with such a process, Kumar said. First, whitefly is at its most dangerous as a nymph, which is when it sucks away at the sap and enfeebles the plant. “The whitefly stage is not so harmful," he said. "All that will happen is the insect will lay the next generation of eggs.”

Second, spraying the flies will not help if it is not coordinated. “All the flies have to do is move to an adjoining field where spraying is not yet underway,” he noted.

Third, the lack of information about the emergent weather patterns meant that the farmers did not spray their fields for a long time. As the Met department noticed, the weather stayed overcast with minor drizzles. This made farmers reluctant to spray “Companies tell farmers that fields should stay dry for four-six hours after spraying," Jagdish said. "And the spray is costly – Rs 1,800/litre. Since farmers were never sure when it would rain, they deferred spraying.”

So the eggs grew undisturbed into mites, with concentrations per leaf much higher than before; the plants weakened and their leaves turned black. Which is when, Kumar said, desperate farmers began looking for medicines – “sprays, synthetics, anything”.

Take Hazara Ram of Balwana. The farmer, now in his sixties, sprayed four different pesticides in a bid to control his whitefly outbreak. None of them worked. His harvest was just 80 kilos from two acres, which netted him no more than Rs 4,000 – against which, he spent Rs 5,000 on pesticides alone.

Sukhdev Singhji. Credit: M Rajshekhar

In this part of India, it is the kharif crop – usually a cash crop like basmati or cotton – that introduces variability into farmers’ annual income. The winter crop, usually sold to the government at fixed rates, is more of a safety net. Like Hazara Ram, Sukhdev Singhji, a resident of Balwana village near Abohar, will not make any money on his cotton crop this year. He will make money only if wheat (kanak, in Punjabi) does well: “Kanak bachave to bachave.”

There is another issue here: Given that whitefly go through four stages – egg, nymph, pupa and adult – how did farmers like Ram know the stage of infection and therefore the appropriate medicines to spray?

They went by what agricultural traders or company agents – whose job is to sell pesticides – told them.

The rise of new 'knowhow'

As Punjab’s extension machinery weakened, other actors stepped into the void – such as companies that sell fertiliser and pesticides. Said the Punjab Agriculture University scientist, “Their agents usually visit villages 15 days before the time of application. If the pesticide doesn’t work, they start working in another village. As it is, they are not even agri-graduates.”

Most of them are very young, said Sukhdev Singhji – “Navey munde. Unhey khud hi nahin pata honda.”

Another entrant into this informational vacuum is the adatiya, the agricultural trader. As an article in the November 7, 2015, issue of the Economic & Political Weekly, titled “Commission Agent System: Significance in Contemporary Agricultural Economy of Punjab”, notes: “They [adatiyas] have become the exploitative alternative for supply of credit, farm and domestic inputs as well as sale of produce. Not only do they provide credit for purchasing essential articles, but also push the farmers to purchase the same from the shops they, or their friends, own.”

One reason for their rise is the worsening economics of agriculture in Punjab.

Take cotton: It is mainly grown in the southern reaches of Punjab, in the Malwa region. On the whole, this is the poorest of the three regions of the state, and the one that sees the most farmer suicides.

Villages in south-western Punjab’s Malwa region are far poorer than villages elsewhere in Punjab.

Credit: M Rajshekhar

Bt Cotton came here in 2004, in response to the American bollworm attacks that started in 1997. Sukhpal Singh, head of Punjab Agricultural University’s Department of Economics and Sociology, points out that since then, though farmer incomes have risen, their debt has not come down.

There are several reasons for this, Singh said. While Bt Cotton was resistant to bollworm, after about seven or eight years of normalcy, attacks from secondary pests started. At the same time, input costs began rising faster than output prices. “It was partly globalisation. Subsidy on input prices was reduced. Diesel and machinery and seeds got costlier. At the same time, international cotton prices fell.”

This is a story that is playing out all across Punjab. As the cost of agriculture rises and its profitability falls, Punjab’s farmers are being pushed into debt – 89% of all farming households are in debt, according to this EPW paper. They borrow from the adatiyas. When the harvest comes in, they give the crop to the adatiyas who sell it, recover the loan, and give the balance to the farmers.

And so, when whiteflys came, most farmers turned to the traders seeking pesticides. The EPW paper estimates that 15.01% of pesticides in Punjab (across all crops) are now supplied from the shops of commission agents, and another 80% are procured from the shops owned by people connected to these agents. They, says the paper, issue “a “slip” to farmers for obtaining items from their “owned or connected shops”.

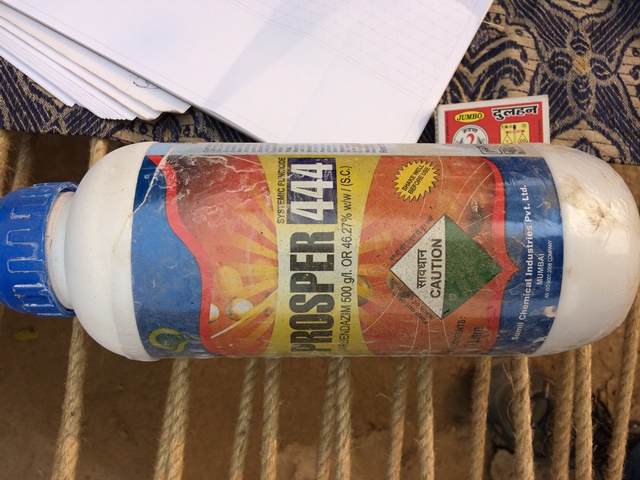

The fungicide that Singhji applied to his cotton fields. Credit: M Rajshekhar

This further compromised farmers’ efforts against whiteflies. There was now the added risk that the traders (who are not farmers) might recommend the wrong pesticide, or one with a greater margin, or that farmers might buy cheaper pesticides to keep their debt low.

Agreed the scientist, “Extension work has collapsed. Paisa nahin hain. Udhaar lena hain. Sasti kaun si hain?”

Singhji, for instance, sprayed a fungicide while trying to take on whitefly.

That won’t work, said Jagdish, the young shop-owner of Balwana, pointing out that farmers sprayed unthinkingly. “Decide kuch nahin kiya, jo mila woh daal diya," he said. They sprayed whatever they could get.

Other farmers underestimated the whitefly crisis and either sprayed the right medicine too late, or used a milder pesticide than they should have. Matters were further complicated by perennial factors like fake pesticides and batch variations. “I see a farmer’s plot after spraying and if there is no change a day later, I send that batch of spray back,” said Jagdish.

That is the arithmetic of this moment. It’s telling that farmers held off spraying as long as the skies stayed overcast – it shows that farmers’ knowhow is static in a world that is changing fast. The state needs to work on mitigation and adaptation. And for that, it needs to prepare its farmers better.

“Our outreach has to be strengthened,” said Surinder Paul of the Met department. “The information is there. But not all farmers are getting it.”

Failing that, the state will only see the turmoil in its farmlands increase.

This is the last part in a series on how climate change in affecting India.

Buy an annual Scroll Membership to support independent journalism and get special benefits.

Our journalism is for everyone. But you can get special privileges by buying an annual Scroll Membership. Sign up today!