Hot water, sanitary pads and bottles are flung at them when they work in filthy, obscure Mumbai gullies (lanes), but although manual scavenging is illegal, Maharashtra employs 35% of 1,80,657 Indian families whose livelihood depends on unblocking excreta-packed sewers in those dank lanes.

“Aamhi lokancha jeev wachavto ashi kama karun pan aamcha jeev wachwayla konich nahi (We save lives by doing our job but there is nobody to save us),” a worker said, requesting anonymity for fear of official retribution.

India does not officially recognise the employment of manual scavengers, almost all of whom are Dalits. They are officially hired as “cleaners” in Maharashtra. The state does, however, acknowledge that thousands make their living doing manual scavenging.

Maharashtra has more than 63,000 households dependent on manual scavenging, followed by Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Tripura and Karnataka, according to a question answered by Minister of State for Social Justice and Empowerment, Vijay Sampla, in the Lok Sabha.

Source: Lok Sabha

The 'sweepers'

Since they do not have a proper system of disposing of excreta, the Indian Railways are the largest employer of manual scavengers, with an unknown number on their rolls.

Most of the “sweepers”, as they are called – thus making them hard to identify as scavengers – with the railways are employed through contractors, and they earn around Rs 200 per day. Although the workers get gloves, hygiene awareness is so low that they hardly use them. If they do use protective equipment, a new draft law says such workers can then no longer be classified as manual scavengers.

In September, the Delhi high court ordered a survey in the capital to determine the extent of manual scavenging. The Ministry of Railways told the court that manual scavenging cannot be completely eradicated until stations get washable aprons and sealed toilet systems.

“While the (railway) ministry denies employing manual scavengers officially, the affidavits it has submitted in the court in the past nine years suggest that barring a few trains, the railways does not employ any technology to keep its 80,000 toilets and 1.15 lakh kilometres of tracks clean,” according to Down To Earth magazine.

Sunil Yadav, from Manual Scavenger to M.Phil: Yadav, 36, a neo-Buddhist, inherited his father’s occupation and was a manual scavenger with the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC). Yadav later completed his Masters in social work, and is currently pursuing an M Phil at Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS). But his is a rare success story among 30,000 conservancy workers employed by the BMC. Most are Dalits and work in these outlawed jobs because they have no choice.

Source: British Broadcasting Corporation

On the margins

Progress for a people who come from the lowest castes and whose jobs do not officially exist is slow, and protest is almost impossible.

Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation “conservancy workers” – an euphemism for manual scavengers who clean lanes –said that they started getting gloves recently. The BMC has also started giving them medical insurance up to Rs 5 lakh. Since the premium is deducted from their salary, more than half have not signed up.

“There are four to five deaths every month,” a worker said. “Most of us suffer from tuberculosis. BMC owns a hospital but all we get is Rs 10 case-paper free." That means the workers don’t have to pay consultation fees, but they must pay for their own medicines and wait six months for sonography tests, four months for x-rays.

Almost all of Mumbai’s conservancy workers in BMC are Buddhists or neo-Buddhists, converts from Hinduism’s lowest castes. Kept to the margins, it is hard for them to break the status quo.

One contractor said that machines now cleaned sewers and workers did not descend manholes. However, workers said contractors sent people down manholes almost every night. Workers take turns entering manholes, lathering bare bodies with coconut oil to keep away the odours of the sewer.

Why do they continue doing what they do?

Housing and jobs

In Mumbai, one of the main reasons why manual scavengers continue doing their jobs is that they do not have the education to do much else. Working as a scavenger means that they get housing from the BMC and their jobs can be transferred to family members.

Although their “official” income varies from Rs 7,000 to Rs 25,000, what they actually get in hand is Rs 5,000 to Rs 15,000, after deductions for education and marriage loans – some taken from landlords – and insurance premia.

A new law, The Prohibition of Employment of Manual Scavengers and Rehabilitation Act, 2013, talks about rehabilitating conservancy workers by giving them one-time cash assistance of Rs 40,000. After talking to BMC workers, it was clear they had not heard of this.

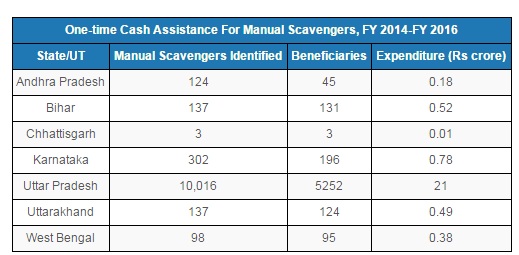

Source: Lok Sabha; Note: Data for FY 2016 up to June 30, 2015.

The Self Employment Scheme for Rehabilitation of Manual Scavengers was introduced by the Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment in 2007, and implementation supposedly began in November 2013. Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Karnataka, Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand and West Bengal have received cash assistance to rehabilitate scavengers identified by the government.

Maharashtra has given no cash to manual scavengers it has identified.

This article was originally published on IndiaSpend, a data-driven and public-interest journalism non-profit.

Scroll has produced award-winning journalism despite violent threats, falling ad revenues and rising costs. Support our work. Become a member today.

In these volatile times, Scroll remains steadfastly courageous, nuanced and comprehensive. Become a Scroll Member and support our award-winning reportage, commentary and culture writing.