Rallies are the high points of an election campaign. They present an opportunity for parties and leaders to show their strength and impress voters with grandeur, like descending from the skies in a helicopters. They are also used to send messages to voters and opponents. Like in the past, a few sentences uttered at rallies for the Bihar assembly election greatly contributed to setting the tone of the campaign. But are these rallies effective for gathering votes?

It’s commonly said that the Bharatiya Janata Party's mega-rallies were largely filled with paid party workers and sympathisers brought from outside. Perched on our office balcony, we recently watched a procession of buses ferrying people to a rally meant for the inauguration of a highway in Haryana. The buses’ colours revealed their state origins – Punjab, Uttar Pradesh, Himachal Pradesh, and Haryana – and we felt that this must have little to do with a highway inauguration.

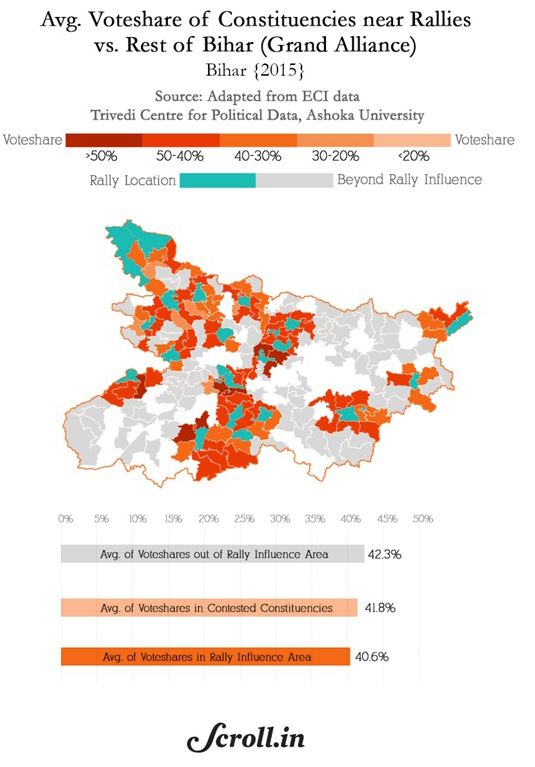

That vignette aside, do we see a varied performance in constituencies where the top party leaders spoke, as opposed to the areas they did not visit? And does the performance differ in seats where rallies were held by the National Democratic Alliance and the Grand Alliance?

We consider here 20 mega rallies held by Narendra Modi and 30 rallies held by various leaders of the Grand Alliance (there were other, smaller rallies, which we did not take into account for lack of precise count).

Wide and varied

In the case of the BJP, there is a 4% positive difference in the vote share between seats where they held a rally and others. Adjacent constituencies sit right in the middle, with a 2% vote share difference.

The BJP won 12 out of the 19 constituencies where it held rallies – a strike rate of 63.2%, which is much higher than its state average of 33.8%. Fourteen of these seats had a sitting BJP legislator, which means that the party chose to conduct rallies in comparatively safer seats.

The analysis for the Grand Alliance is more complicated as there were at least four main speakers involved – Lalu Prasad Yadav (5 rallies), Nitish Kumar (11), Rahul Gandhi and Sonia Gandhi (14). These leaders also held rallies in seats where other partners fielded a candidate (none for the Rashtriya Janata Dal, seven for Janata Dal (United), and eight for the Congress). There were eight constituencies which were visited by more than one party.

Different strategies

The first observation is that most of the rallies took place in western Bihar, including a cluster in West Champaran. These were mostly seats in the north-west being contested by RJD and Congress candidates. And while Lalu Prasad Yadav seems to have exclusively campaigned in seats contested by RJD candidates, both Nitish Kumar and Rahul Gandhi covered seats across party lines.

What we see here is a negative relation: the average vote share in constituencies where these leaders did not contest was on an average nearly 2% higher. We should not necessarily deduce that their rallies were less effective. It could very well mean that the Grand Alliance leaders chose to rally in difficult seats. Thirteen of the seats in which they conducted a rally had a sitting BJP MLA. The BJP retained eight of these seats. So all in all, the data shows that these rallies were not very effective.

Rahul Gandhi campaigned in the four seats won by the Congress in 2010. The party retained all these seats. He campaigned in six BJP-held seats, of which the Congress lost four. The Congress strike rate is therefore 50%.

The RJD won 40% of the seats where its leaders held rallies, losing in Motihari, Kanti and Patna Sahib.

Winning nine seats out of 11, the JD(U) had a strike rate of 82% – higher than the Grand Alliance’s average of 73.3%.

Personal touch

What all this means is that is actually still hard to tell whether rallies proved effective. The BJP had a good return on its investment, but it held rallies in safer seats. The Grand Alliance did not rally uniformly across the state. The result was a mixed bag, particularly in seats which had an incumbent from the opposition parties.

The reality is that it is very difficult to isolate the rally effect from other variables of the campaign. It is possible and plausible that the door-to-door campaign organised by the Alliance and its overall communication strategies were more effective than large rallies. RJD and JD(U) leaders also held a large number of low-key local rallies that were less boisterous. but enabled closer interaction with voters.

The experience across India and abroad indicates that these personal campaigns are more persuasive and yield better results than large impersonal events.

However, the nature of the rally, its location, timing and the venue are all good indicators of the parties’ strategies. The BJP may not have wanted to expose the Prime Minister too much and so chose to have him speak on conquered ground. The Grand Alliance’s strategy was to rally more aggressively on enemy turf.

Effective or not, rallies also represent an expression of hubris on the part of political leaders – what’s not to love about a large, adoring crowd? It’s for that reason alone that rallies are here to stay.

Data support: Karthik Shankar; Infographic: Kaustubh Khare, Devika Prakash; QGIS mapping: Aafaque Raza Khan. Rally data by Venkata Pingali, Fourthlion (Bangalore).

It’s commonly said that the Bharatiya Janata Party's mega-rallies were largely filled with paid party workers and sympathisers brought from outside. Perched on our office balcony, we recently watched a procession of buses ferrying people to a rally meant for the inauguration of a highway in Haryana. The buses’ colours revealed their state origins – Punjab, Uttar Pradesh, Himachal Pradesh, and Haryana – and we felt that this must have little to do with a highway inauguration.

That vignette aside, do we see a varied performance in constituencies where the top party leaders spoke, as opposed to the areas they did not visit? And does the performance differ in seats where rallies were held by the National Democratic Alliance and the Grand Alliance?

We consider here 20 mega rallies held by Narendra Modi and 30 rallies held by various leaders of the Grand Alliance (there were other, smaller rallies, which we did not take into account for lack of precise count).

Wide and varied

In the case of the BJP, there is a 4% positive difference in the vote share between seats where they held a rally and others. Adjacent constituencies sit right in the middle, with a 2% vote share difference.

The BJP won 12 out of the 19 constituencies where it held rallies – a strike rate of 63.2%, which is much higher than its state average of 33.8%. Fourteen of these seats had a sitting BJP legislator, which means that the party chose to conduct rallies in comparatively safer seats.

The analysis for the Grand Alliance is more complicated as there were at least four main speakers involved – Lalu Prasad Yadav (5 rallies), Nitish Kumar (11), Rahul Gandhi and Sonia Gandhi (14). These leaders also held rallies in seats where other partners fielded a candidate (none for the Rashtriya Janata Dal, seven for Janata Dal (United), and eight for the Congress). There were eight constituencies which were visited by more than one party.

Different strategies

The first observation is that most of the rallies took place in western Bihar, including a cluster in West Champaran. These were mostly seats in the north-west being contested by RJD and Congress candidates. And while Lalu Prasad Yadav seems to have exclusively campaigned in seats contested by RJD candidates, both Nitish Kumar and Rahul Gandhi covered seats across party lines.

What we see here is a negative relation: the average vote share in constituencies where these leaders did not contest was on an average nearly 2% higher. We should not necessarily deduce that their rallies were less effective. It could very well mean that the Grand Alliance leaders chose to rally in difficult seats. Thirteen of the seats in which they conducted a rally had a sitting BJP MLA. The BJP retained eight of these seats. So all in all, the data shows that these rallies were not very effective.

Rahul Gandhi campaigned in the four seats won by the Congress in 2010. The party retained all these seats. He campaigned in six BJP-held seats, of which the Congress lost four. The Congress strike rate is therefore 50%.

The RJD won 40% of the seats where its leaders held rallies, losing in Motihari, Kanti and Patna Sahib.

Winning nine seats out of 11, the JD(U) had a strike rate of 82% – higher than the Grand Alliance’s average of 73.3%.

Personal touch

What all this means is that is actually still hard to tell whether rallies proved effective. The BJP had a good return on its investment, but it held rallies in safer seats. The Grand Alliance did not rally uniformly across the state. The result was a mixed bag, particularly in seats which had an incumbent from the opposition parties.

The reality is that it is very difficult to isolate the rally effect from other variables of the campaign. It is possible and plausible that the door-to-door campaign organised by the Alliance and its overall communication strategies were more effective than large rallies. RJD and JD(U) leaders also held a large number of low-key local rallies that were less boisterous. but enabled closer interaction with voters.

The experience across India and abroad indicates that these personal campaigns are more persuasive and yield better results than large impersonal events.

However, the nature of the rally, its location, timing and the venue are all good indicators of the parties’ strategies. The BJP may not have wanted to expose the Prime Minister too much and so chose to have him speak on conquered ground. The Grand Alliance’s strategy was to rally more aggressively on enemy turf.

Effective or not, rallies also represent an expression of hubris on the part of political leaders – what’s not to love about a large, adoring crowd? It’s for that reason alone that rallies are here to stay.

Data support: Karthik Shankar; Infographic: Kaustubh Khare, Devika Prakash; QGIS mapping: Aafaque Raza Khan. Rally data by Venkata Pingali, Fourthlion (Bangalore).

Limited-time offer: Big stories, small price. Keep independent media alive. Become a Scroll member today!

Our journalism is for everyone. But you can get special privileges by buying an annual Scroll Membership. Sign up today!