A woman was 18 when she “ran into the jungle” to join the cultural troupe of the Communist Party of India (Maoist), but surrendered in 2011 after her husband became ill. A man does not buy fertilisers so that he can preserve native varieties of rice. A group of children proclaims that they are neither police informers nor Maoist sympathisers “just like you”.

These are stories that have featured in Humans of Gondwana, a new Facebook project by young Chhattisgarh-based journalists who are travelling to villages and settlements in the heart of India to bring their stories to a wider audience.

The project is based on photographer Brandon Stanton’s immensely popular Humans of New York. The concept is simple. Ask people on the street about themselves, take a portrait and post both online. The result is a series that can be anything from insightful to mundane.

Humans of Gondwana is named for the Central Gondwana Region, the geographic area in and around Chhattisgarh. The subjects of their photographs are tribals, not just Gonds, who live in this region.

“If you look at Humans of Bombay or of any other city, they all show urban communities,” said Ramesh, one of the three, who requested not to be fully identified. “This is unique because we are more rural.”

One of the three journalists is a photographer. They record audio on their mobile phones, translate the Gondi into English and Hindi and upload all three versions of the story online. They take care to ensure nothing is changed or edited.

“We used to travel a lot in Chhattisgarh and forest regions around as a part of our jobs,” said Ramesh, one of the three. “We spoke to many people, so we also had lots of stories and photos.”

They began collecting stories and photos around a year ago, but began posting them only in August.

The group emphasises consent. Before taking photos or recording stories, they explain how many people could view it. They do not, like Stanton, ask specific questions, but ask what people would like to share about their lives. And unlike Humans of New York, Ramesh and his group sporadically identify some of the people in their photos with their names and villages.

“We have been wondering how justifiable it is to romanticise the idea of tribal people,” Ramesh said. “It is something we are still struggling with.”

Many stories are about the loss of old cultural traditions. Sukhiya Habka of Bhamragarh in Maharashtra spoke of how children in his village no longer learned how to decorate brass because the metal was too expensive.

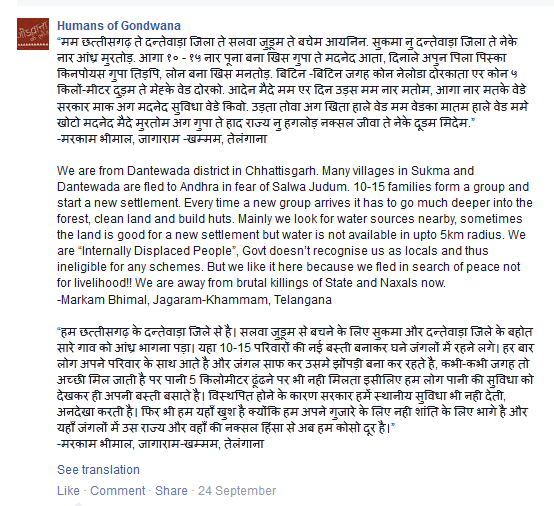

Ramesh personally found stories from Khammam, where there are internally displaced people, “soul-crushing”. These people, forced to shift after being caught in violence from the Salwa Judum and Maoists, now stay in Andhra Pradesh where they are not recognised by the state or accepted by local tribes.

“I like the idea to have stories from the streets,” Ramesh said, of Humans of New York. “Many people do want to share stories about themselves and this is a good way to do it.”

These are stories that have featured in Humans of Gondwana, a new Facebook project by young Chhattisgarh-based journalists who are travelling to villages and settlements in the heart of India to bring their stories to a wider audience.

The project is based on photographer Brandon Stanton’s immensely popular Humans of New York. The concept is simple. Ask people on the street about themselves, take a portrait and post both online. The result is a series that can be anything from insightful to mundane.

Humans of Gondwana is named for the Central Gondwana Region, the geographic area in and around Chhattisgarh. The subjects of their photographs are tribals, not just Gonds, who live in this region.

“If you look at Humans of Bombay or of any other city, they all show urban communities,” said Ramesh, one of the three, who requested not to be fully identified. “This is unique because we are more rural.”

One of the three journalists is a photographer. They record audio on their mobile phones, translate the Gondi into English and Hindi and upload all three versions of the story online. They take care to ensure nothing is changed or edited.

“We used to travel a lot in Chhattisgarh and forest regions around as a part of our jobs,” said Ramesh, one of the three. “We spoke to many people, so we also had lots of stories and photos.”

They began collecting stories and photos around a year ago, but began posting them only in August.

The group emphasises consent. Before taking photos or recording stories, they explain how many people could view it. They do not, like Stanton, ask specific questions, but ask what people would like to share about their lives. And unlike Humans of New York, Ramesh and his group sporadically identify some of the people in their photos with their names and villages.

“We have been wondering how justifiable it is to romanticise the idea of tribal people,” Ramesh said. “It is something we are still struggling with.”

Many stories are about the loss of old cultural traditions. Sukhiya Habka of Bhamragarh in Maharashtra spoke of how children in his village no longer learned how to decorate brass because the metal was too expensive.

Ramesh personally found stories from Khammam, where there are internally displaced people, “soul-crushing”. These people, forced to shift after being caught in violence from the Salwa Judum and Maoists, now stay in Andhra Pradesh where they are not recognised by the state or accepted by local tribes.

“I like the idea to have stories from the streets,” Ramesh said, of Humans of New York. “Many people do want to share stories about themselves and this is a good way to do it.”

Limited-time offer: Big stories, small price. Keep independent media alive. Become a Scroll member today!

Our journalism is for everyone. But you can get special privileges by buying an annual Scroll Membership. Sign up today!