In his first interview as Australian Prime Minister with The Today Show on Monday, Malcolm Turnbull responded to questions about increased funding for women escaping family violence by declaring “real men don’t hit women”.

Given recent statistics on the prevalence of violence against women in Australia, it’s impossible to overstate the importance of this message.

But while the prime minister’s words are significant, just as crucial is the task of encouraging leaders in politics and the media to echo them. Only then can we begin to reshape how society thinks about relations between men and women in Australia.

But what are the current cultural messages about relations between women themselves?

The recent conclusion in media and popular culture seems to be that while women do not hit other women, they invariably hit out at one another. There is nothing new about this idea.

“Mean girls”?

In the past decade, sociological findings have sought to demonstrate that bullying among girls takes the form of relational aggression – verbal and emotional abuse – as opposed to the physical aggression found among boys.

This has sparked debate about “mean girls” of all ages. But it is not just a sub-set of females who are said to engage in “girl-on-girl crime”.

Rather, incidents of back-stabbing or gossiping between high-profile women, as well as “bitchy” comments about female celebrities on social media, have been seized as proof that hostility is a natural state among all women.

Journalists gleefully report on Twitter battles between celebrities such as Taylor Swift and Nicki Minaj, Beyonce and Rihanna, and Khloe Kardashian and Amber Rose.

The premise that women will lash out at each other in order to compete for male attention is also used for entertainment, as on The Bachelor and the Real Housewives of Melbourne. Or for comedic value, as in Chris Rock’s stand-up routine.

Given monikers like “veminism” and “sororal cannibalism”, viciousness towards other women is framed as an age-old and expected part of female behavior.

Yet social commentators also treat the “mean girl” stereotype as a new discovery, or part of the human condition only recently acknowledged.

A myth with a longer history

In reality, the belief that women secretly hate one another has a long history.

For centuries, women were pronounced incapable of “true” friendship. Victorians celebrated romantic friendships between women, but also depicted them as superficial passions that simply prepared women for marriage.

Rather than enjoying the long-lasting friendships found among men, bonds between women were depicted as short-lived, unable to withstand women’s quarrelsome natures.

On Women (1851), by German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer, declared that the feeling between male strangers or acquaintances was “mere indifference”; for women it was “actual enmity”.

Similarly, Unitarian minister and writer William Rounseville Alger, in The Friendships of Women (1868), concluded:

Worse, underlying animosity was portrayed making these relationships potentially dangerous. At its most extreme, female friendships were thought to induce women to criminal acts.

As nineteenth-century criminal anthropologist Cesare Lombroso argued in Criminal Woman, the Prostitute and the Normal Woman (1893):

Australia inherited this western cultural tradition of demonising relationships between women. It is no wonder that Australian historian Nick Dyrenfurth found mateship to have been a “steadfastly male” institution in his recent history on the subject.

A biological imperative?

For many past and the present commentators, the main reason women supposedly lack sorority is thought to be sexual jealousy.

It is alleged this could even be biological - a drive left over from a period when securing male support was necessary to female survival.

Indeed, Lombroso was one of the first to espouse this Darwinian view of female relations. He claimed that competition for “resources” led to an instinctive hatred of their own sex among both animal and human females.

While such contentions remain unproven, they have proved influential.

In the nineteenth century, such sentiments made women scapegoats for their own suffering. Prostitution was blamed not on capitalism, but on the vindictiveness of those already in the trade. Victorian sex workers reputedly sought to “drag down” other women to their level.

There was “the feeling” among prostitutes of “the fox who has lost his tail and wants to get all the other foxes to have their tails cut off too”, suffragist Agnes Maude Royden suggested in her 1916 book Downward Paths.

Conversely, “respectable” women were accused of enforcing the moral standards that prevented the rehabilitation of “fallen women”. For nineteenth-century Melbournian journalist “The Vagabond” John Stanley James, it was “woman alone” - never man - that cast “stones at her erring sister”.

This perspective continues in society today. According to commentators like Samantha Brick, it is women, not men, who objectify, belittle and sabotage attractive women, especially those who have embraced their sexuality.

Professional women

Women may have been freed from their reliance on a male provider during the twentieth century, but this is not said to have lessened female rivalry. Rather, this phenomenon is seen to have simply moved into the professional sphere.

Many believe female bosses are tougher on women employees, reluctant to help others shatter the glass ceiling for fear of losing their own privileged position.

A 2011 psychological study concluded that accusations of “Queen Bee” behaviour usually resulted from women being held to different professional standards. Competitiveness and authoritarianism, researchers found, were perceived negatively when displayed by women, but not men.

Again, such perceptions are nothing new.

In the illicit economy of the nineteenth century, brothel-keepers were described as jealously guarding the more privileged position they held over the ordinary prostitute. Madams were said to cheat other women out of their wages with a sense of schadenfreude.

There were similar allegations of female exploitation in the legitimate economy. Social reformer Helen Campbell, in Prisoners of Poverty (1900), an investigation of American female factory workers, declared:

The myth continues

Whether in their professional or personal lives, it is true that women do not always treat other women well. But the same can be said for men.

We could just as easily find evidence that all men hate each other - for example, by pointing out that the majority of violent crime is by men against other men.

Yet centuries of being told women are each others worst enemies has resulted in confirmation bias. We are programmed to identify evidence that supports the pre-existing hypothesis.

And when stories of female rivalry grace our screens – for example, between mothers in The Hand that Rocks the Cradle (1992), the four-girl clique in Pretty Little Liars (2010-present) and rival crime queens in Underbelly: Razor (2011) – these narratives are simply more titillating than the prosaic reality of male violence.

A preoccupation with girl-on-girl “crime” not only distracts from the greater problems women face, such as the violence committed against them by men, but to some extent validates the women-as-lesser attitudes that contribute to such crimes.

Cultural critic HL Mencken once defined a misogynist as a man who hates women as much as women hate one another. Glibly suggesting that all women hate each other gives tacit permission for men to hate women too.

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

Given recent statistics on the prevalence of violence against women in Australia, it’s impossible to overstate the importance of this message.

But while the prime minister’s words are significant, just as crucial is the task of encouraging leaders in politics and the media to echo them. Only then can we begin to reshape how society thinks about relations between men and women in Australia.

But what are the current cultural messages about relations between women themselves?

The recent conclusion in media and popular culture seems to be that while women do not hit other women, they invariably hit out at one another. There is nothing new about this idea.

“Mean girls”?

In the past decade, sociological findings have sought to demonstrate that bullying among girls takes the form of relational aggression – verbal and emotional abuse – as opposed to the physical aggression found among boys.

This has sparked debate about “mean girls” of all ages. But it is not just a sub-set of females who are said to engage in “girl-on-girl crime”.

Rather, incidents of back-stabbing or gossiping between high-profile women, as well as “bitchy” comments about female celebrities on social media, have been seized as proof that hostility is a natural state among all women.

Journalists gleefully report on Twitter battles between celebrities such as Taylor Swift and Nicki Minaj, Beyonce and Rihanna, and Khloe Kardashian and Amber Rose.

The premise that women will lash out at each other in order to compete for male attention is also used for entertainment, as on The Bachelor and the Real Housewives of Melbourne. Or for comedic value, as in Chris Rock’s stand-up routine.

Given monikers like “veminism” and “sororal cannibalism”, viciousness towards other women is framed as an age-old and expected part of female behavior.

Yet social commentators also treat the “mean girl” stereotype as a new discovery, or part of the human condition only recently acknowledged.

A myth with a longer history

In reality, the belief that women secretly hate one another has a long history.

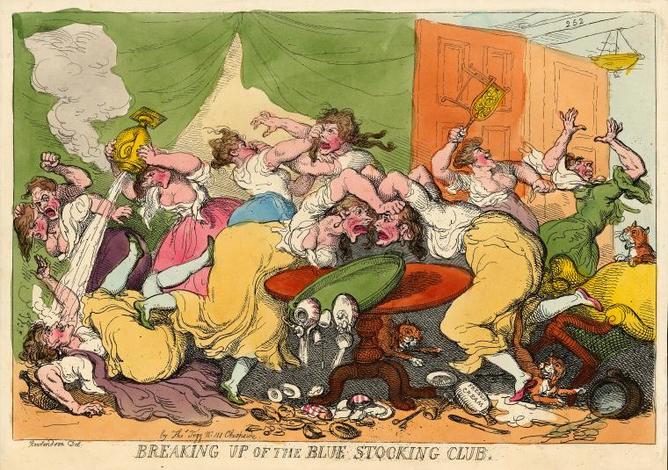

Carl H. Pforzheimer, Breaking up of the Blue Stocking Club (1815). New York Public Library Digital Collections, CC BY

For centuries, women were pronounced incapable of “true” friendship. Victorians celebrated romantic friendships between women, but also depicted them as superficial passions that simply prepared women for marriage.

Rather than enjoying the long-lasting friendships found among men, bonds between women were depicted as short-lived, unable to withstand women’s quarrelsome natures.

On Women (1851), by German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer, declared that the feeling between male strangers or acquaintances was “mere indifference”; for women it was “actual enmity”.

Similarly, Unitarian minister and writer William Rounseville Alger, in The Friendships of Women (1868), concluded:

I was often struck both by the small number of recorded examples of the sentiment among women […] and by the commonness of the expressed belief, that strong natural obstacles make friendship a comparatively feeble and rare experience with them.

Worse, underlying animosity was portrayed making these relationships potentially dangerous. At its most extreme, female friendships were thought to induce women to criminal acts.

As nineteenth-century criminal anthropologist Cesare Lombroso argued in Criminal Woman, the Prostitute and the Normal Woman (1893):

Due to women’s latent antipathy for one another, trivial events give rise to fierce hatreds; and due to women’s irascibility, these occasions lead quickly to insolence and assaults. […] Women of high social station do the same thing, but their more refined forms of insult do not lead to law courts.

Australia inherited this western cultural tradition of demonising relationships between women. It is no wonder that Australian historian Nick Dyrenfurth found mateship to have been a “steadfastly male” institution in his recent history on the subject.

A biological imperative?

For many past and the present commentators, the main reason women supposedly lack sorority is thought to be sexual jealousy.

It is alleged this could even be biological - a drive left over from a period when securing male support was necessary to female survival.

Indeed, Lombroso was one of the first to espouse this Darwinian view of female relations. He claimed that competition for “resources” led to an instinctive hatred of their own sex among both animal and human females.

While such contentions remain unproven, they have proved influential.

In the nineteenth century, such sentiments made women scapegoats for their own suffering. Prostitution was blamed not on capitalism, but on the vindictiveness of those already in the trade. Victorian sex workers reputedly sought to “drag down” other women to their level.

There was “the feeling” among prostitutes of “the fox who has lost his tail and wants to get all the other foxes to have their tails cut off too”, suffragist Agnes Maude Royden suggested in her 1916 book Downward Paths.

Conversely, “respectable” women were accused of enforcing the moral standards that prevented the rehabilitation of “fallen women”. For nineteenth-century Melbournian journalist “The Vagabond” John Stanley James, it was “woman alone” - never man - that cast “stones at her erring sister”.

This perspective continues in society today. According to commentators like Samantha Brick, it is women, not men, who objectify, belittle and sabotage attractive women, especially those who have embraced their sexuality.

Professional women

Women may have been freed from their reliance on a male provider during the twentieth century, but this is not said to have lessened female rivalry. Rather, this phenomenon is seen to have simply moved into the professional sphere.

Many believe female bosses are tougher on women employees, reluctant to help others shatter the glass ceiling for fear of losing their own privileged position.

A 2011 psychological study concluded that accusations of “Queen Bee” behaviour usually resulted from women being held to different professional standards. Competitiveness and authoritarianism, researchers found, were perceived negatively when displayed by women, but not men.

Again, such perceptions are nothing new.

In the illicit economy of the nineteenth century, brothel-keepers were described as jealously guarding the more privileged position they held over the ordinary prostitute. Madams were said to cheat other women out of their wages with a sense of schadenfreude.

There were similar allegations of female exploitation in the legitimate economy. Social reformer Helen Campbell, in Prisoners of Poverty (1900), an investigation of American female factory workers, declared:

[Female industrial supervisors are] not only as filled with greed and as tricky and uncertain in their methods as the worst class of male employers, but even more ingenious in specific modes of imposition.

The myth continues

Whether in their professional or personal lives, it is true that women do not always treat other women well. But the same can be said for men.

We could just as easily find evidence that all men hate each other - for example, by pointing out that the majority of violent crime is by men against other men.

Yet centuries of being told women are each others worst enemies has resulted in confirmation bias. We are programmed to identify evidence that supports the pre-existing hypothesis.

And when stories of female rivalry grace our screens – for example, between mothers in The Hand that Rocks the Cradle (1992), the four-girl clique in Pretty Little Liars (2010-present) and rival crime queens in Underbelly: Razor (2011) – these narratives are simply more titillating than the prosaic reality of male violence.

A preoccupation with girl-on-girl “crime” not only distracts from the greater problems women face, such as the violence committed against them by men, but to some extent validates the women-as-lesser attitudes that contribute to such crimes.

Cultural critic HL Mencken once defined a misogynist as a man who hates women as much as women hate one another. Glibly suggesting that all women hate each other gives tacit permission for men to hate women too.

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

Limited-time offer: Big stories, small price. Keep independent media alive. Become a Scroll member today!

Our journalism is for everyone. But you can get special privileges by buying an annual Scroll Membership. Sign up today!