In 1896, at the end of his second trip to India, the American artist Edwin Lord Weeks wrote From the Black Sea through Persia and India. It was a travel account that, packed with his illustrations, detailed his journey around Asia. A change in his original travel plans because of the civil war in Afghanistan and a cholera outbreak had meant that he had to travel first on camelback and then on horses from Turkey through Persia, following the old caravan route (the Silk Route) till he reached Bushire on the Persian Gulf. Here he boarded a steamer for Karachi travelling via Aden and Muscat, before moving on to Bombay.

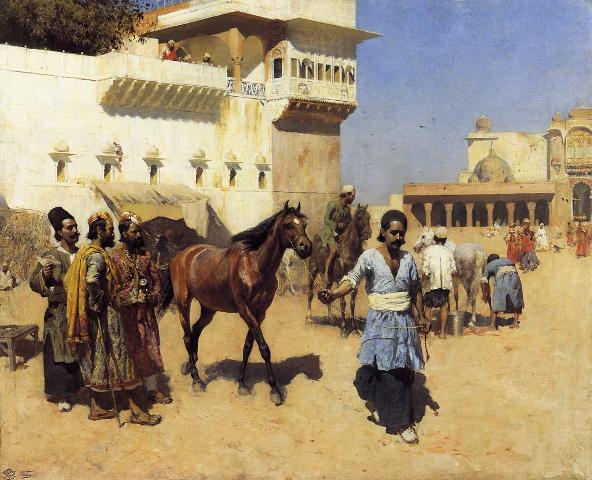

The steamer, Weeks noted, was used for the export of horses, for its deck resembled a “floating stable”. On landing in Bombay, most of the horses were moved to the horse market at Byculla to meet the demand for “Polo ponies and cavalry service”. His sketch of that scene and other moments from the country’s life would many decades later give him the appellation “the finest painter of Victorian India”.

Weeks, born into a wealthy trading family in Massachusetts in 1849, had long been enamoured of the East. By his time, Orientalism had already exercised an influence on European artists, an interest that grew following Napoleon’s early 19th campaign in North Africa and Egypt. Weeks made the first of his trips to Morocco and Syria in the 1870s and then studied in Paris with the painter Leon Bonnat, who was known for his detailed portraiture and religious depictions. Weeks also knew Jean Leon Gerome, an artist from an earlier generation of Orientalist painters who had travelled to Egypt.

In his works, Weeks revealed himself as more than just an Orientalist painter – he was also a fine writer. His book and articles, which he illustrated himself, affirmed his keen interest in the world around him and his love for the outdoors.

There was also a fascination for colour and an eye for detail in his work. His photographs, especially those taken during his earlier trips to Asia in the 1870s and 1880s, served as the base for his paintings. You can see in them his focus on the daily lives, of royalty and commoners alike. His street scenes catch, for example, the daily congregation of an assorted group of people in Lahore. He revelled in the blueness of houses in Jodhpur, the dazzling whiteness of Udaipur (Oudeypore), and the pink structures of Jaipur (Jeypore).

Extremely well-read, Weeks was an astute analyst of the political events of his time which he recorded as he made use of the relatively new innovations in Asia such as the railway. From Karachi, Weeks took a train running by the Indus to Lahore. The military presence was strong since Lahore was only 19 hours by train from Peshawar, a strongly defended frontier city. In the streets of Lahore, there were shops offering tobacco products and second-hand furniture as well as nautch girls observing all the hustle from their overhanging balconies. During his stay in the city, Weeks made sketches of the famous mosque of Wazir Khan and the life around it.

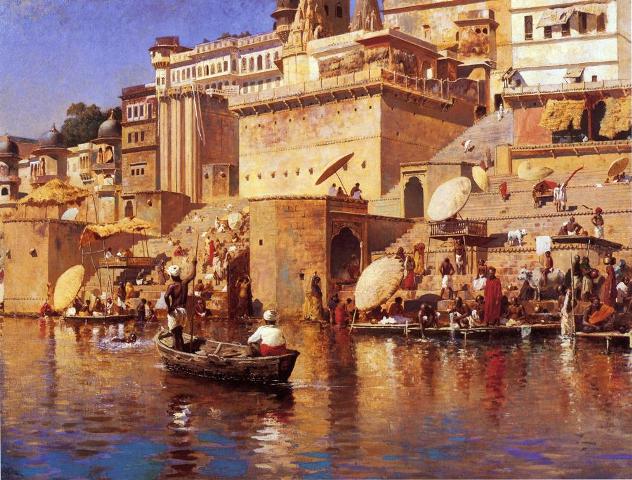

Mendicants, or fakirs, made recurring appearance in his works. He noticed them wherever he went. Like in Benaras, a town where the sacred mingled with the profane. (It was here that Weeks was also invited to a watch a nautch girl’s performance.)

Matching the American painter’s fascination for the outdoors was his passion for crafts. His street scenes show in detail the intricate lattice work on almost every balcony and window.

The tomb of Anarkali in Lahore, once a “favourite of Akbar”, was now a church, he wrote. Several other ancient buildings in India, Weeks noted almost mournfully, had been converted into offices for the use of bureaucrats. “In those early days of plunder and conquest (by the ‘John Company’), horses were stabled in memorial tombs and palaces, audience halls converted into powder magazines, barracks or offices of district magnates…whatever could be adapted or altered for use of the conqueror was spared, the rest pulled down.”

The many Mughal buildings at Sikri and Agra were worth every bit of admiration, but Weeks singled out the tomb of Salim Chisti for its high degree of craftsmanship. Shah Jahan’s building efforts even outmatched those of Louis XIV, the Bourbon king of France. And the Taj Mahal, for all its excellence, was rivalled by the Diwan-i-Khas, the palace at Delhi.

Amritsar, only 30 miles from Lahore, was a “city of polemics”. The Golden Temple was “a glittering jewel or some rare old Byzantine casket wrought with enamel and studded with gems”. The one jarring note however was the European style clock tower at its entrance.

Unusually for his times, Weeks wrote with indignation about the cruel treatment of animals. Tigers, he noted, were no longer a danger on long road journeys for they had been hunted so much. The cheetah, a creature soon to be extinct, was often used in fighting competitions. On a train to Jodhpur – newly introduced by its maharaja – he noticed a cheetah strung up in a charpoy and travelling in the third class.

Jodhpur’s fort, with its museum of ancient armaments, looked down over the city, and presented an awesome spectacle, as hard to climb as the Matterhorn itself. (Weeks had also penned a book on his mountaineering adventures in the Alps.) The rajas had their own fads and eccentricities. Some boasted of killing tigers single-handedly. Some proudly professed having just one wife and not women-filled harems. Some, such as the Maharaja of Gwalior, maintained a huge stable, equipped with the finest carriages made in London and Paris.

When Weeks was in Bombay in August 1893, the cow protection riots happened to break out. One of the vital problems of governance in India, Weeks wrote, was maintaining harmony between the religions. The “cow issue”, as the newspapers termed it, was a major source of conflict and was heightened by extremists on both sides. The Hindu writer of a book titled the Tohfa-i-Hind, considered eating beef, introduced by the British, as the main cause of leprosy and the occurrence of famines in India.

Bombay’s mix of modernity and tradition fascinated Weeks in every way. He suffered much nightly grief from mosquitoes – for the punkah-wallahs invariably slept on their jobs – but enjoyed evenings at the Yacht Club. Besides, Bombay had its snake-charmers and the temple at Walkeshwar. And, despite the presence of his very inebriated Irish landlord, the mornings in Malabar were particularly pleasant.

The steamer, Weeks noted, was used for the export of horses, for its deck resembled a “floating stable”. On landing in Bombay, most of the horses were moved to the horse market at Byculla to meet the demand for “Polo ponies and cavalry service”. His sketch of that scene and other moments from the country’s life would many decades later give him the appellation “the finest painter of Victorian India”.

Horse Market, Persian Stables, Bombay

Weeks, born into a wealthy trading family in Massachusetts in 1849, had long been enamoured of the East. By his time, Orientalism had already exercised an influence on European artists, an interest that grew following Napoleon’s early 19th campaign in North Africa and Egypt. Weeks made the first of his trips to Morocco and Syria in the 1870s and then studied in Paris with the painter Leon Bonnat, who was known for his detailed portraiture and religious depictions. Weeks also knew Jean Leon Gerome, an artist from an earlier generation of Orientalist painters who had travelled to Egypt.

In his works, Weeks revealed himself as more than just an Orientalist painter – he was also a fine writer. His book and articles, which he illustrated himself, affirmed his keen interest in the world around him and his love for the outdoors.

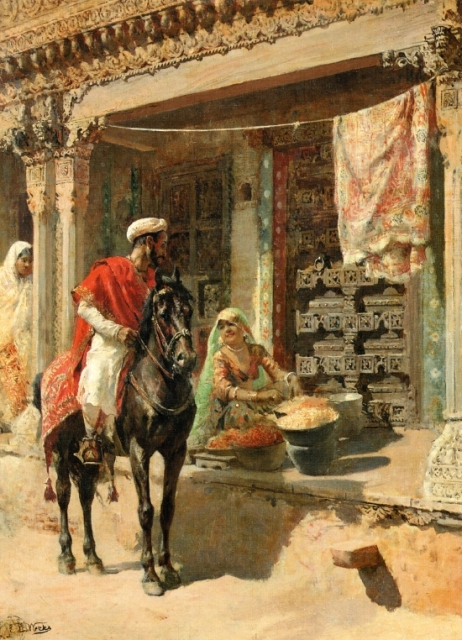

There was also a fascination for colour and an eye for detail in his work. His photographs, especially those taken during his earlier trips to Asia in the 1870s and 1880s, served as the base for his paintings. You can see in them his focus on the daily lives, of royalty and commoners alike. His street scenes catch, for example, the daily congregation of an assorted group of people in Lahore. He revelled in the blueness of houses in Jodhpur, the dazzling whiteness of Udaipur (Oudeypore), and the pink structures of Jaipur (Jeypore).

Street Vendor, Ahmedabad.

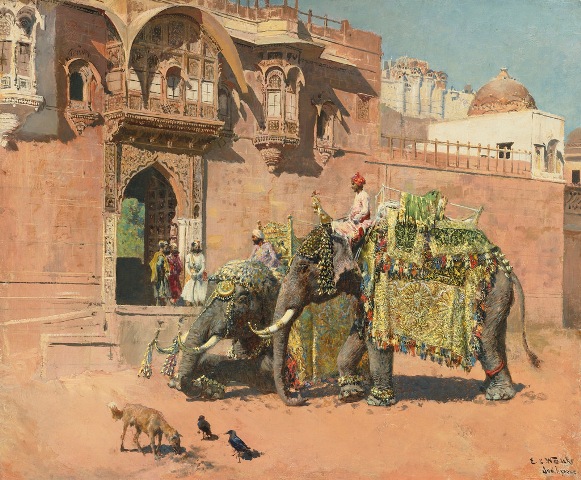

Elephants of the Jodhpore Raja.

Marketplace, Agra.

Extremely well-read, Weeks was an astute analyst of the political events of his time which he recorded as he made use of the relatively new innovations in Asia such as the railway. From Karachi, Weeks took a train running by the Indus to Lahore. The military presence was strong since Lahore was only 19 hours by train from Peshawar, a strongly defended frontier city. In the streets of Lahore, there were shops offering tobacco products and second-hand furniture as well as nautch girls observing all the hustle from their overhanging balconies. During his stay in the city, Weeks made sketches of the famous mosque of Wazir Khan and the life around it.

Steps of the mosque of Wazir Khan at Lahore

Mendicants, or fakirs, made recurring appearance in his works. He noticed them wherever he went. Like in Benaras, a town where the sacred mingled with the profane. (It was here that Weeks was also invited to a watch a nautch girl’s performance.)

By the river at Benaras.

Nautch girl.

Matching the American painter’s fascination for the outdoors was his passion for crafts. His street scenes show in detail the intricate lattice work on almost every balcony and window.

The tomb of Anarkali in Lahore, once a “favourite of Akbar”, was now a church, he wrote. Several other ancient buildings in India, Weeks noted almost mournfully, had been converted into offices for the use of bureaucrats. “In those early days of plunder and conquest (by the ‘John Company’), horses were stabled in memorial tombs and palaces, audience halls converted into powder magazines, barracks or offices of district magnates…whatever could be adapted or altered for use of the conqueror was spared, the rest pulled down.”

Sandstone arches at Agra Fort.

Portico of a mosque, Ahmedabad.

The many Mughal buildings at Sikri and Agra were worth every bit of admiration, but Weeks singled out the tomb of Salim Chisti for its high degree of craftsmanship. Shah Jahan’s building efforts even outmatched those of Louis XIV, the Bourbon king of France. And the Taj Mahal, for all its excellence, was rivalled by the Diwan-i-Khas, the palace at Delhi.

Fatehpur Sikri.

Amritsar, only 30 miles from Lahore, was a “city of polemics”. The Golden Temple was “a glittering jewel or some rare old Byzantine casket wrought with enamel and studded with gems”. The one jarring note however was the European style clock tower at its entrance.

The Golden Temple.

Unusually for his times, Weeks wrote with indignation about the cruel treatment of animals. Tigers, he noted, were no longer a danger on long road journeys for they had been hunted so much. The cheetah, a creature soon to be extinct, was often used in fighting competitions. On a train to Jodhpur – newly introduced by its maharaja – he noticed a cheetah strung up in a charpoy and travelling in the third class.

Jodhpur’s fort, with its museum of ancient armaments, looked down over the city, and presented an awesome spectacle, as hard to climb as the Matterhorn itself. (Weeks had also penned a book on his mountaineering adventures in the Alps.) The rajas had their own fads and eccentricities. Some boasted of killing tigers single-handedly. Some proudly professed having just one wife and not women-filled harems. Some, such as the Maharaja of Gwalior, maintained a huge stable, equipped with the finest carriages made in London and Paris.

The Maharaja and the Palace at Gwalior.

When Weeks was in Bombay in August 1893, the cow protection riots happened to break out. One of the vital problems of governance in India, Weeks wrote, was maintaining harmony between the religions. The “cow issue”, as the newspapers termed it, was a major source of conflict and was heightened by extremists on both sides. The Hindu writer of a book titled the Tohfa-i-Hind, considered eating beef, introduced by the British, as the main cause of leprosy and the occurrence of famines in India.

Bombay’s mix of modernity and tradition fascinated Weeks in every way. He suffered much nightly grief from mosquitoes – for the punkah-wallahs invariably slept on their jobs – but enjoyed evenings at the Yacht Club. Besides, Bombay had its snake-charmers and the temple at Walkeshwar. And, despite the presence of his very inebriated Irish landlord, the mornings in Malabar were particularly pleasant.

Bombay snake charmers.

Buy an annual Scroll Membership to support independent journalism and get special benefits.

Our journalism is for everyone. But you can get special privileges by buying an annual Scroll Membership. Sign up today!