“When I lived in Pakistan, I lived as a Hindu, [but] when I migrated to India in search of safety and dignity, I have been given a cold shoulder for being a Pakistani,” lamented Amar Ram, 20, who migrated to India in April last year.

His complaint illustrates the irony of the bind in which the thousands of Hindus who leave Pakistan to escape persistent harassment find themselves. When they arrive in India, they are viewed suspiciously by many people and are treated callously by the government that has done little to help them settle in.

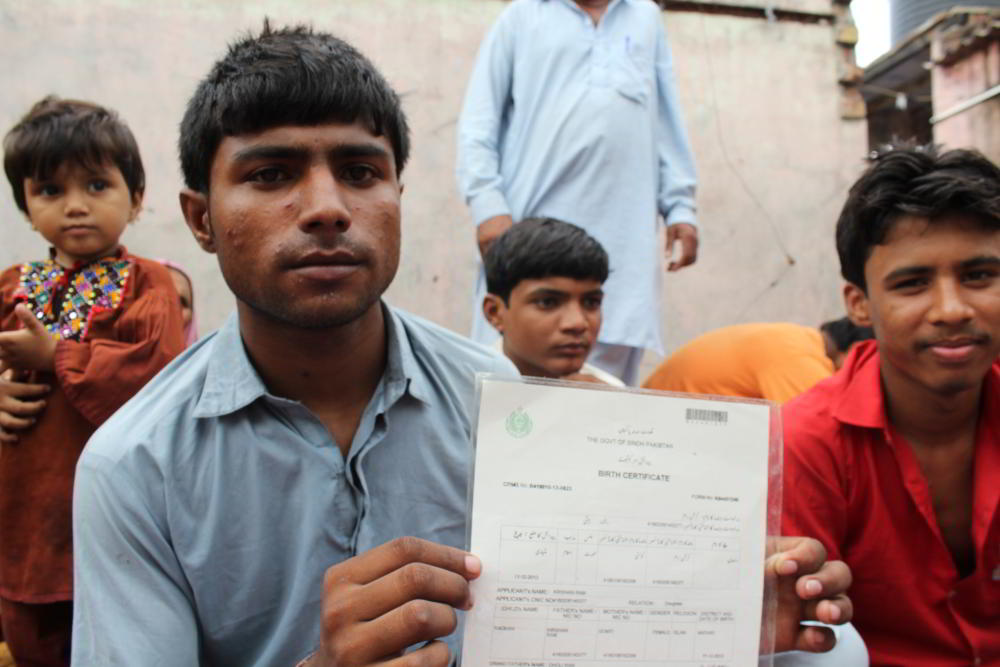

But Ram and others like him have one less thing to fret about. On Monday, the government announced that Bangladeshis and Pakistanis belonging to minority communities there, who had entered India legally before December 31 could stay in the country, even if their documents had lapsed. That will bring some relief to Ram and 24 other residents of Matiari district of Sindh in Pakistan, who arrived in Delhi on pilgrimage visas in April 2014. The pilgrim visas have expired, as have most of their Pakistani passports.

However, merely giving migrants the right to stay in India isn't enough. Social and economic assistance is vital if the migrants want to give India their best shot. Said Satram, 63, “Our neighbours don’t talk to us because of my Pakistani papers. Nobody even hires me for any work.”

Religious persecution

The refugees from Pakistan mostly land up in Rajasthan as the short journey from Thar Express makes it convenient for them, but lately many of them are heading for a rural settlement called Bijwasan on the outskirts of Delhi.

For Kishan Ram, 32, the decision to migrate to India was a tough one, as he had to leave behind his newborn child because he could not get her a passport. “The authorities denied a passport to my younger child, so I had to leave her behind at my brother’s place,” he said. “My wife and my elder daughter accompanied me as soon as we got the pilgrim visa for India.”

Jamna Devi, 50, who spent almost her entire life in Pakistan, crossed the border with great expectations. “Women are also disrespected there, “ she said. “We had to face verbal jibes, sometimes they were directed at us, sometimes towards our religion and customs. We were scared, however, coming here has been no good for us until now as people don’t treat us well here either. We are being neglected both by society and the Indian government.”

Dr Ramesh Kumar Vankwani, a member of the ruling Pakistan Muslim League and also the patron of the Pakistan Hindu Council, said in Pakistan's National Assembly last year that around 5,000 Hindus from Pakistan migrate to India every year due to religious persecution.

The last census of Pakistan in 1998 recorded around 2.5 million Hindus. According to the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan data, around 1,000 Hindu families fled to India in 2013.

Shattered dreams

Since 2011, more than 900 Pakistani Hindus have been living around Delhi, most of them in Bijwasan, where they are squeezed more than 20 to a room in a former school.

It is even more difficult for younger people because their Pakistani schooling certificates are not recognised as a result of which they are not being able to work at their full capacity, forcing them to do odd jobs as street hawkers. Raja, 26, completed his schooling till the twelfth standard in Pakistan but fears for his future. “I cannot study here, nor can I find any job," he said. "Nobody lends any help. I am educated but still I have to sell things on thestreets.”

Their custodian in Delhi is a 61-year-old former customs officer and policeman Nahar Singh, who said the cost of feeding and housing these refugees is borne by various Hindu groups such as the Vishva Hindu Parishad and the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh. “I have made repeated attempts requesting the government to grant them citizenship,” he said. “But in these years I have received no confirmation from the Indian authorities”

Broken Promises

Among the campaigners for Pakistani Hindus is Singh Sodha,, who migrated to India in 1971. "There is no law in India which answers the problems faced by the Hindu migrants from Pakistan." he said. Since India is not a signatory to the 1951 United Nations Refugee Convention that grants persecuted migrants refugee status, it refuses to recognise Pakistani Hindus as refugees, he said. For now, people have to wait for seven years before they can apply for Indian citizenship under the Indian Citizenship Act of 1955. However, there is no guarantee how long it would take to get citizenship, if at all.

The Bharatiya Janata Party had earlier claimed that they had granted Indian citizenship to 4,300 Pakistani nationals during 2014-'15. However, a response to a query filed under Right to Information by Seemant Lok Sanghthan showed that only 289 Pakistani Hindus were granted Indian citizenship in this period.

In 1978, around 55,000 Pakistani were granted Indian citizenship. In 2005, the number stood at 13,000. Over the recent years due to the cross-border tensions, the refugees have been treated with more suspicion and hostility.

His complaint illustrates the irony of the bind in which the thousands of Hindus who leave Pakistan to escape persistent harassment find themselves. When they arrive in India, they are viewed suspiciously by many people and are treated callously by the government that has done little to help them settle in.

But Ram and others like him have one less thing to fret about. On Monday, the government announced that Bangladeshis and Pakistanis belonging to minority communities there, who had entered India legally before December 31 could stay in the country, even if their documents had lapsed. That will bring some relief to Ram and 24 other residents of Matiari district of Sindh in Pakistan, who arrived in Delhi on pilgrimage visas in April 2014. The pilgrim visas have expired, as have most of their Pakistani passports.

However, merely giving migrants the right to stay in India isn't enough. Social and economic assistance is vital if the migrants want to give India their best shot. Said Satram, 63, “Our neighbours don’t talk to us because of my Pakistani papers. Nobody even hires me for any work.”

Religious persecution

The refugees from Pakistan mostly land up in Rajasthan as the short journey from Thar Express makes it convenient for them, but lately many of them are heading for a rural settlement called Bijwasan on the outskirts of Delhi.

For Kishan Ram, 32, the decision to migrate to India was a tough one, as he had to leave behind his newborn child because he could not get her a passport. “The authorities denied a passport to my younger child, so I had to leave her behind at my brother’s place,” he said. “My wife and my elder daughter accompanied me as soon as we got the pilgrim visa for India.”

Jamna Devi, 50, who spent almost her entire life in Pakistan, crossed the border with great expectations. “Women are also disrespected there, “ she said. “We had to face verbal jibes, sometimes they were directed at us, sometimes towards our religion and customs. We were scared, however, coming here has been no good for us until now as people don’t treat us well here either. We are being neglected both by society and the Indian government.”

Dr Ramesh Kumar Vankwani, a member of the ruling Pakistan Muslim League and also the patron of the Pakistan Hindu Council, said in Pakistan's National Assembly last year that around 5,000 Hindus from Pakistan migrate to India every year due to religious persecution.

The last census of Pakistan in 1998 recorded around 2.5 million Hindus. According to the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan data, around 1,000 Hindu families fled to India in 2013.

Shattered dreams

Since 2011, more than 900 Pakistani Hindus have been living around Delhi, most of them in Bijwasan, where they are squeezed more than 20 to a room in a former school.

It is even more difficult for younger people because their Pakistani schooling certificates are not recognised as a result of which they are not being able to work at their full capacity, forcing them to do odd jobs as street hawkers. Raja, 26, completed his schooling till the twelfth standard in Pakistan but fears for his future. “I cannot study here, nor can I find any job," he said. "Nobody lends any help. I am educated but still I have to sell things on thestreets.”

Their custodian in Delhi is a 61-year-old former customs officer and policeman Nahar Singh, who said the cost of feeding and housing these refugees is borne by various Hindu groups such as the Vishva Hindu Parishad and the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh. “I have made repeated attempts requesting the government to grant them citizenship,” he said. “But in these years I have received no confirmation from the Indian authorities”

Broken Promises

Among the campaigners for Pakistani Hindus is Singh Sodha,, who migrated to India in 1971. "There is no law in India which answers the problems faced by the Hindu migrants from Pakistan." he said. Since India is not a signatory to the 1951 United Nations Refugee Convention that grants persecuted migrants refugee status, it refuses to recognise Pakistani Hindus as refugees, he said. For now, people have to wait for seven years before they can apply for Indian citizenship under the Indian Citizenship Act of 1955. However, there is no guarantee how long it would take to get citizenship, if at all.

The Bharatiya Janata Party had earlier claimed that they had granted Indian citizenship to 4,300 Pakistani nationals during 2014-'15. However, a response to a query filed under Right to Information by Seemant Lok Sanghthan showed that only 289 Pakistani Hindus were granted Indian citizenship in this period.

In 1978, around 55,000 Pakistani were granted Indian citizenship. In 2005, the number stood at 13,000. Over the recent years due to the cross-border tensions, the refugees have been treated with more suspicion and hostility.

Limited-time offer: Big stories, small price. Keep independent media alive. Become a Scroll member today!

Our journalism is for everyone. But you can get special privileges by buying an annual Scroll Membership. Sign up today!