This much we know. Hardik Patel wants Other Backward Class status for the Patidar community. After a dramatic rally in Gujarat and a flying visit to Delhi, he plans to take his movement to other parts of the country, drawing in other groups like the Kurmis and Gujjars. But how much do we know for sure about OBC reservations? The Patel agitation has resurrected some old questions.

Who are the OBCs?

Unlike Scheduled Castes, OBCs did not have to face untouchability. Unlike Scheduled Tribes, they were not geographically isolated and cut off from the currents of modernity. Unlike both SCs and STs, there are no lists of groups who qualify for this category.

Article 15(4) mentions “socially and educationally backward classes” and Article 16(4) speaks of “backward class citizens”. But the Constitution does not define who they are. The First Backward Classes Commission, set up in 1953, laid down that an OBC community had to belong to the lower orders of the traditional caste hierarchy. It was a criterion that stuck, though it would be refined by later commissions. The Mandal Commission, set up in 1979 by the Janata Party government under Prime Minister Morarji Desai, used social, educational as well as economic criteria for OBC claims, though it gave social criteria the most weightage.

Essentially, OBC status looked at social and educational backwardness as a function of caste. But the boundaries of backwardness are constantly shifting and often politically determined. Historically, OBCs have tended to be agrarian communities or those involved in rural occupations such as fishing or pottery.

What does OBC status mean in real terms?

The Mandal Commission report, tabled in 1990, recommended 27% reservation for OBCs in government services, and in all scientific, professional and technical institutions run by the central as well as state governments. Most visibly, it has come to mean reserved seats in universities and colleges.

In 2006, the Supreme Court mandated 27% reservation in centrally-run institutions of higher education. This included the Indian Institutes of Technology, the Indian Institutes of Management and the All India Institute of Medical Sciences. Though central institutes have had to put OBC quotas in place over the last decade, many states have had more long-running quotas.

A key objective for policies of reservation is to ensure that OBCs are adequately represented. This means that a community’s share in the population should match its share in the number of students going to college or the number of individuals employed in government services.

What is the 'creamy layer exception'?

The Supreme Court, in 1992, held that OBC reservations were valid, though socially advanced sections of the backward classes should be excluded from quotas. A year later, a government committee produced its report on criteria for exclusion. These included the children of people who had held constitutional posts or plum government jobs, of senior army officers, of professionals and businessmen above a prescribed income limit, of large property owners and of those who pass the “income/wealth test”. The last category made exceptions for those who drew income from agricultural land.

The minimum income for the creamy layer has been revised upwards over the last two decades, going from Rs 1 lakh in 1993 to Rs 6 lakh in 2013. But the income limit is still a matter of debate. In 2011, the National Commission for Backward Classes had recommended that only people earning above Rs 12 lakh in urban areas and Rs 9 lakh in other place be excluded. It also recommended that the exception for agricultural incomes be done away with. Various states also proposed their own income limits.

However, the line between the creamy layer and others has always been nebulous. The Supreme Court has laid down that income could not be the sole marker of social advancement, that drawing the income line should not undermine reservation and lead to quota seats lying vacant.

A National Commission for Backward Classes report published this year recommends the income limit be raised to Rs 10.5 lakh and that children of elected representatives at the state and central level also be excluded from quotas.

How have reservations worked in government services and institutions?

Actually the whole exercise of reserving seats for OBCs has been rather nebulous. At the institutional level, there is no clarity on who should qualify, neither is their sufficient data. The National Commission for Backward Classes report from 2015 said it was unable to find data on all the recruitments made for central government services, public sector undertakings, banks, insurance organisations and universities in the last three years. There was no nodal agency that held this information and no monitoring or evaluation of whether OBC reservations were being implemented across the country. The report noted that in a range of government departments, the representation of OBCs lies between 0% and 12%. It blamed the vacancies on the “unrealistic” income limit for exclusion.

How have OBC quotas in educational institutions worked?

That again is a matter of debate. In 2014, Jaya Goyal and DP Singh published a paper titled “Academic Performance of OBC students in Universities: Findings from Three States”. It was based on a longer survey conducted by the Tata Institute of Social Sciences, starting in 2007. The paper looked at the performance of OBC students across states to draw conclusions about the “actual nature of their representation and marginalisation”.

Three states were chosen as case studies: Tamil Nadu, Uttar Pradesh and Maharashtra. It concentrated on institutions offering medical, engineering and other technical courses.

In all three states, it found there was little difference between the performance of OBC students and those from the general category in the final examinations. But it found that states with a longer history of reservation and strong social reform movements, like Tamil Nadu and Maharashtra, had generally fared better in reducing inequalities.

The paper had a tricky take on representation of OBCs in higher education and the lack of it. Under-representation, it suggested, should be defined as a “community’s share in the population availing college” being “less than its share of the population that is actually qualified to enter college”, that is, those who had completed their school education.

So across the country, the percentage of OBCs, aged 18-29, who cleared higher secondary education was negligibly lower than those who had become graduates. This seemed to suggest that there was little discrimination at the college level. “Comparing the enrolment of OBCs in Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra and UP, they are well-represented and have performed almost on a par with the general category at the exit level in most professional streams of higher education.” And this was the case before the apex court even imposed 27% quota in central institutions.

In a rejoinder, Sai Thakur questioned both the finding and the redefinition. “Calculating under-representation only in comparison with the proportion of those from the concerned social group who are able to pass their HSC, and not with their population share, goes against the very logic of India’s reservation policy.” Very large numbers get rooted out at the school level because of their backwardness or the quality of education that the state provides, not because of their individual capabilities. “There are various social, economic and cultural hurdles that these marginalised groups have to cross to reach the 10th and the 12th standards,” Thakur argued.

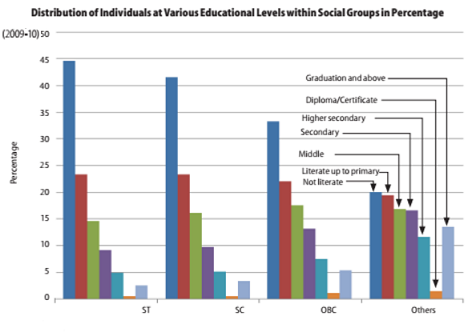

The attrition rates are dramatic at every stage of education, and particularly high for some communities, as the table below shows.

Government policies on reservation are ad hoc, badly defined, poorly implemented and not monitored. Until these ambiguities are erased, the granting or withholding of OBC status will always be considered suspect, motivated by politics rather than social justice. In the process, a very large number of people fighting social and educational disadvantages could lose out.

Who are the OBCs?

Unlike Scheduled Castes, OBCs did not have to face untouchability. Unlike Scheduled Tribes, they were not geographically isolated and cut off from the currents of modernity. Unlike both SCs and STs, there are no lists of groups who qualify for this category.

Article 15(4) mentions “socially and educationally backward classes” and Article 16(4) speaks of “backward class citizens”. But the Constitution does not define who they are. The First Backward Classes Commission, set up in 1953, laid down that an OBC community had to belong to the lower orders of the traditional caste hierarchy. It was a criterion that stuck, though it would be refined by later commissions. The Mandal Commission, set up in 1979 by the Janata Party government under Prime Minister Morarji Desai, used social, educational as well as economic criteria for OBC claims, though it gave social criteria the most weightage.

Essentially, OBC status looked at social and educational backwardness as a function of caste. But the boundaries of backwardness are constantly shifting and often politically determined. Historically, OBCs have tended to be agrarian communities or those involved in rural occupations such as fishing or pottery.

What does OBC status mean in real terms?

The Mandal Commission report, tabled in 1990, recommended 27% reservation for OBCs in government services, and in all scientific, professional and technical institutions run by the central as well as state governments. Most visibly, it has come to mean reserved seats in universities and colleges.

In 2006, the Supreme Court mandated 27% reservation in centrally-run institutions of higher education. This included the Indian Institutes of Technology, the Indian Institutes of Management and the All India Institute of Medical Sciences. Though central institutes have had to put OBC quotas in place over the last decade, many states have had more long-running quotas.

A key objective for policies of reservation is to ensure that OBCs are adequately represented. This means that a community’s share in the population should match its share in the number of students going to college or the number of individuals employed in government services.

What is the 'creamy layer exception'?

The Supreme Court, in 1992, held that OBC reservations were valid, though socially advanced sections of the backward classes should be excluded from quotas. A year later, a government committee produced its report on criteria for exclusion. These included the children of people who had held constitutional posts or plum government jobs, of senior army officers, of professionals and businessmen above a prescribed income limit, of large property owners and of those who pass the “income/wealth test”. The last category made exceptions for those who drew income from agricultural land.

The minimum income for the creamy layer has been revised upwards over the last two decades, going from Rs 1 lakh in 1993 to Rs 6 lakh in 2013. But the income limit is still a matter of debate. In 2011, the National Commission for Backward Classes had recommended that only people earning above Rs 12 lakh in urban areas and Rs 9 lakh in other place be excluded. It also recommended that the exception for agricultural incomes be done away with. Various states also proposed their own income limits.

However, the line between the creamy layer and others has always been nebulous. The Supreme Court has laid down that income could not be the sole marker of social advancement, that drawing the income line should not undermine reservation and lead to quota seats lying vacant.

A National Commission for Backward Classes report published this year recommends the income limit be raised to Rs 10.5 lakh and that children of elected representatives at the state and central level also be excluded from quotas.

How have reservations worked in government services and institutions?

Actually the whole exercise of reserving seats for OBCs has been rather nebulous. At the institutional level, there is no clarity on who should qualify, neither is their sufficient data. The National Commission for Backward Classes report from 2015 said it was unable to find data on all the recruitments made for central government services, public sector undertakings, banks, insurance organisations and universities in the last three years. There was no nodal agency that held this information and no monitoring or evaluation of whether OBC reservations were being implemented across the country. The report noted that in a range of government departments, the representation of OBCs lies between 0% and 12%. It blamed the vacancies on the “unrealistic” income limit for exclusion.

How have OBC quotas in educational institutions worked?

That again is a matter of debate. In 2014, Jaya Goyal and DP Singh published a paper titled “Academic Performance of OBC students in Universities: Findings from Three States”. It was based on a longer survey conducted by the Tata Institute of Social Sciences, starting in 2007. The paper looked at the performance of OBC students across states to draw conclusions about the “actual nature of their representation and marginalisation”.

Three states were chosen as case studies: Tamil Nadu, Uttar Pradesh and Maharashtra. It concentrated on institutions offering medical, engineering and other technical courses.

In all three states, it found there was little difference between the performance of OBC students and those from the general category in the final examinations. But it found that states with a longer history of reservation and strong social reform movements, like Tamil Nadu and Maharashtra, had generally fared better in reducing inequalities.

The paper had a tricky take on representation of OBCs in higher education and the lack of it. Under-representation, it suggested, should be defined as a “community’s share in the population availing college” being “less than its share of the population that is actually qualified to enter college”, that is, those who had completed their school education.

So across the country, the percentage of OBCs, aged 18-29, who cleared higher secondary education was negligibly lower than those who had become graduates. This seemed to suggest that there was little discrimination at the college level. “Comparing the enrolment of OBCs in Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra and UP, they are well-represented and have performed almost on a par with the general category at the exit level in most professional streams of higher education.” And this was the case before the apex court even imposed 27% quota in central institutions.

In a rejoinder, Sai Thakur questioned both the finding and the redefinition. “Calculating under-representation only in comparison with the proportion of those from the concerned social group who are able to pass their HSC, and not with their population share, goes against the very logic of India’s reservation policy.” Very large numbers get rooted out at the school level because of their backwardness or the quality of education that the state provides, not because of their individual capabilities. “There are various social, economic and cultural hurdles that these marginalised groups have to cross to reach the 10th and the 12th standards,” Thakur argued.

The attrition rates are dramatic at every stage of education, and particularly high for some communities, as the table below shows.

Source: NSSO(2012)

Government policies on reservation are ad hoc, badly defined, poorly implemented and not monitored. Until these ambiguities are erased, the granting or withholding of OBC status will always be considered suspect, motivated by politics rather than social justice. In the process, a very large number of people fighting social and educational disadvantages could lose out.

Scroll has produced award-winning journalism despite violent threats, falling ad revenues and rising costs. Support our work. Become a member today.

In these volatile times, Scroll remains steadfastly courageous, nuanced and comprehensive. Become a Scroll Member and support our award-winning reportage, commentary and culture writing.