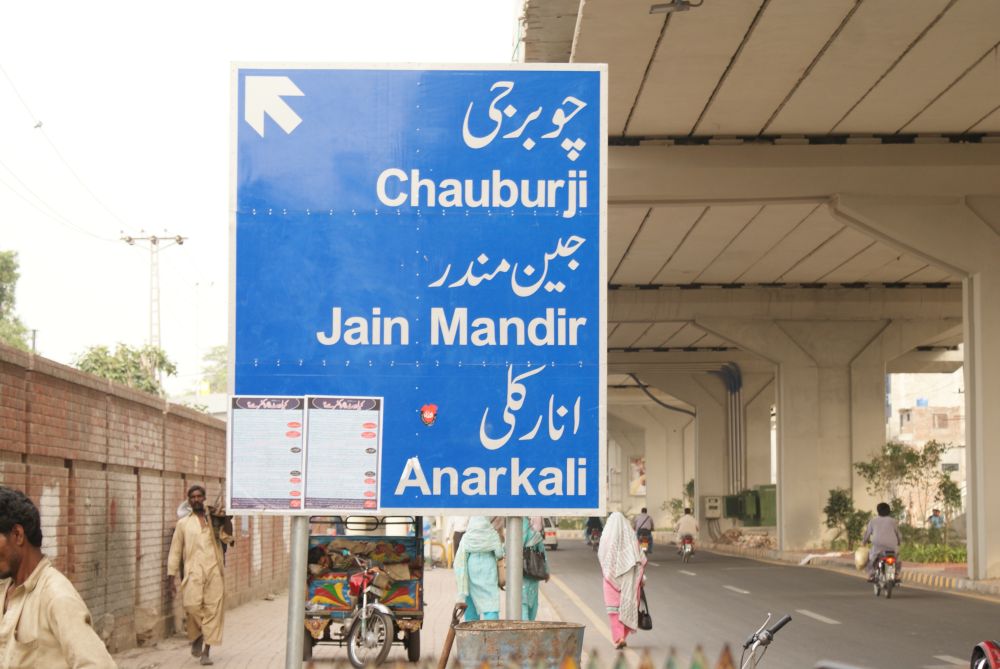

After the historical town of Ichra, the Ferozepur Road forks into two, as indicated by the Lahore Development Authority’s blue signboard. One of these roads is marked Jain Mandar Chowk.

Not far from here is the site of the historical temple that once proudly stood here. Today, its tall turret lies defeated in the middle of a ground enclosed on all sides by a protective wall. The enclosure has an iron gate, which is permanently closed. This part of our history is better off locked away.

A mochi sits outside the wall. Across the road from him stand the remains of quarters constructed for priests and pilgrims but now inhabited by traders and residents. The temple was built in the early half of the 20th century and soon became a part of the city’s landscape. Even when Jains left Lahore following Partition the temple remained, becoming one of the city’s most important landmarks.

Jain Mandar Chowk connected the city’s three main roads. There was no escaping the non-Muslim past.

Competitive revisionism

Forty-five years after Partition, the temple was brought down by the people of the very city that had honoured it. In December 1992, following the demolition of Babri mosque in Ayodhya, the Jain Mandar was demolished by a mob in Lahore. To them, the difference between Jains and Hindus was irrelevant. Some people petitioned the government to change the name of the chowk to Babri Masjid chowk, which became the official name.

Two and a half decades later, the name ‘Jain Mandar Chowk’ lives on in the popular imagination. Wagon, rickshaw and taxi drivers, street vendors, residents and pedestrians continue to use it to describe the area. The riots of Partition, the events of December 1992 and a government sanction could not change that. The blue board on the Ferozepur Road put up by the government represents the resilience of certain identities.

Jain Mandar Chowk was lucky in that sense. The new name, proposed in a moment of passion, was never gained acceptance. But other places have a dichotomy – between the state narrative and that of the people. About 50 kilometres from Lahore lies a small historical town called Bhai Pheru. In the middle of this town is a Gurdwara honouring the memory of a devoted Sikh named Bhai Pheru. He was given this title by the seventh guru of Sikhism, Har Rai, when he visited this place and was impressed by the devotion of this man. The name of the town now is a cause of concern to a nascent national identity.

After Pakistan came into being, it gradually distanced itself from its “Indian” heritage, believing that that would dilute its raison d’être. Attempts were made to remove all traces of the Hindu past from the education system. The Gandhara and Indus valley civilisations were robbed of their Hindu heritage and studied as isolated civilisations with no connection to the Ganges civilisation.

The language was Arabised to differentiate it further from Hindi. Cultural traditions shared with people across the border were jettisoned to keep alive the nationalist agenda. Festivals suchas Baisakhi, Lohri and Basant were abandoned as they were thought to be “Hindu” influences that corrupted the pure Muslim culture of Pakistan. Even today, there are calls to ban Indian movies and television in Pakistan as they bring along an “alien” culture that corrupts our society.

Resilience of history

Despite such a rapid nationalisation enterprise, there are small towns, villages and cities scattered all over the country that are a testament to its “impure” past. Some names have been changed but others survive. A few years ago, Bhai Pheru was renamed Phool Nagar, a more religiously neutral name. And unlike the mistake made with Jain Mandar, all official boards also call it Phool Nagar. But the old and new names survive in parallel. Bhai Pheru is still known by its original name and that is how it is referred to in unofficial correspondence.

Another interesting case is that of a locality called Krishan Nagar. This was a Hindu-dominated area in pre-Partition Lahore. There was a splendid Hindu temple here dedicated to the god Krishna, which gave the locality its name. The temple gave way to makeshift houses in the aftermath of the influx of refugees following Partition. Officially, the name of the locality was changed to Islampura to reflect the changing landscape. But in daily conversation, no one refers to it by its new name. Even the local media refers to Krishan Nagar by its original name.

There are also a few cases where non-Muslim names have been completely ignored by government authorities and allowed to survive. One is that of Killa Gujjar Singh, a small town within the city of Lahore, where Gujjar Singh constructed a fort for himself in the 18th century, before Punjab was swept away by Maharaja Ranjit Singh.

The case of Gujjar Singh is an interesting anomaly in the context of Pakistani historiography. The Sikh era in Pakistani textbooks is depicted as a dark period for Muslims, when mosques were desecrated and Muslims were persecuted. There is no reference to Sikh architecture and heritage in the history of this land. Yet crying out loudly its association with this land is this locality of Killa Gujjar Singh and several other such towns and villages.

This situation of non-Muslim names of localities in Pakistan represents a unique case. On the one hand, there is a complete abandonment of Sikh and Hindu history in Pakistan. History begins with the Buddhist era, moves into the Muslim invasion, flourishes in the Mughal period and then culminates with British rule in India and Partition.

Contradicting these claims are these names, which survive as an anomaly in post-Partition, post-multi-religious-Pakistan. What is even more exciting is that even where attempts have been made to change these names they have survived. That is a testimony to the tradition of oral history in our part of the world.

Despite state attempts these stories and these names survive. A drive on any of the national highways in Pakistan will be full of such pleasant surprises, of towns called Wan Radha Ram, Kot Kishen Ganga, Laxman Chauntra, and Sita Gund. It seems as if it will not be easy to erase these names from our collective memory.

Haroon Khalid is the author of A White Trail and two forthcoming books, In Search of Shiva and Walking with Nanak.

Not far from here is the site of the historical temple that once proudly stood here. Today, its tall turret lies defeated in the middle of a ground enclosed on all sides by a protective wall. The enclosure has an iron gate, which is permanently closed. This part of our history is better off locked away.

A mochi sits outside the wall. Across the road from him stand the remains of quarters constructed for priests and pilgrims but now inhabited by traders and residents. The temple was built in the early half of the 20th century and soon became a part of the city’s landscape. Even when Jains left Lahore following Partition the temple remained, becoming one of the city’s most important landmarks.

Jain Mandar Chowk connected the city’s three main roads. There was no escaping the non-Muslim past.

The temple's gone. Photo: Alie Imran

Competitive revisionism

Forty-five years after Partition, the temple was brought down by the people of the very city that had honoured it. In December 1992, following the demolition of Babri mosque in Ayodhya, the Jain Mandar was demolished by a mob in Lahore. To them, the difference between Jains and Hindus was irrelevant. Some people petitioned the government to change the name of the chowk to Babri Masjid chowk, which became the official name.

Two and a half decades later, the name ‘Jain Mandar Chowk’ lives on in the popular imagination. Wagon, rickshaw and taxi drivers, street vendors, residents and pedestrians continue to use it to describe the area. The riots of Partition, the events of December 1992 and a government sanction could not change that. The blue board on the Ferozepur Road put up by the government represents the resilience of certain identities.

But the name remains. Photo: Alie Imran

Jain Mandar Chowk was lucky in that sense. The new name, proposed in a moment of passion, was never gained acceptance. But other places have a dichotomy – between the state narrative and that of the people. About 50 kilometres from Lahore lies a small historical town called Bhai Pheru. In the middle of this town is a Gurdwara honouring the memory of a devoted Sikh named Bhai Pheru. He was given this title by the seventh guru of Sikhism, Har Rai, when he visited this place and was impressed by the devotion of this man. The name of the town now is a cause of concern to a nascent national identity.

After Pakistan came into being, it gradually distanced itself from its “Indian” heritage, believing that that would dilute its raison d’être. Attempts were made to remove all traces of the Hindu past from the education system. The Gandhara and Indus valley civilisations were robbed of their Hindu heritage and studied as isolated civilisations with no connection to the Ganges civilisation.

The language was Arabised to differentiate it further from Hindi. Cultural traditions shared with people across the border were jettisoned to keep alive the nationalist agenda. Festivals suchas Baisakhi, Lohri and Basant were abandoned as they were thought to be “Hindu” influences that corrupted the pure Muslim culture of Pakistan. Even today, there are calls to ban Indian movies and television in Pakistan as they bring along an “alien” culture that corrupts our society.

Killa Gujjar Singh, partially preserved. Photo: Haroon Khalid

Resilience of history

Despite such a rapid nationalisation enterprise, there are small towns, villages and cities scattered all over the country that are a testament to its “impure” past. Some names have been changed but others survive. A few years ago, Bhai Pheru was renamed Phool Nagar, a more religiously neutral name. And unlike the mistake made with Jain Mandar, all official boards also call it Phool Nagar. But the old and new names survive in parallel. Bhai Pheru is still known by its original name and that is how it is referred to in unofficial correspondence.

Another interesting case is that of a locality called Krishan Nagar. This was a Hindu-dominated area in pre-Partition Lahore. There was a splendid Hindu temple here dedicated to the god Krishna, which gave the locality its name. The temple gave way to makeshift houses in the aftermath of the influx of refugees following Partition. Officially, the name of the locality was changed to Islampura to reflect the changing landscape. But in daily conversation, no one refers to it by its new name. Even the local media refers to Krishan Nagar by its original name.

Lakhpat Street at Ichra. Photo: Haroon Khalid

There are also a few cases where non-Muslim names have been completely ignored by government authorities and allowed to survive. One is that of Killa Gujjar Singh, a small town within the city of Lahore, where Gujjar Singh constructed a fort for himself in the 18th century, before Punjab was swept away by Maharaja Ranjit Singh.

The case of Gujjar Singh is an interesting anomaly in the context of Pakistani historiography. The Sikh era in Pakistani textbooks is depicted as a dark period for Muslims, when mosques were desecrated and Muslims were persecuted. There is no reference to Sikh architecture and heritage in the history of this land. Yet crying out loudly its association with this land is this locality of Killa Gujjar Singh and several other such towns and villages.

This situation of non-Muslim names of localities in Pakistan represents a unique case. On the one hand, there is a complete abandonment of Sikh and Hindu history in Pakistan. History begins with the Buddhist era, moves into the Muslim invasion, flourishes in the Mughal period and then culminates with British rule in India and Partition.

Contradicting these claims are these names, which survive as an anomaly in post-Partition, post-multi-religious-Pakistan. What is even more exciting is that even where attempts have been made to change these names they have survived. That is a testimony to the tradition of oral history in our part of the world.

Despite state attempts these stories and these names survive. A drive on any of the national highways in Pakistan will be full of such pleasant surprises, of towns called Wan Radha Ram, Kot Kishen Ganga, Laxman Chauntra, and Sita Gund. It seems as if it will not be easy to erase these names from our collective memory.

Haroon Khalid is the author of A White Trail and two forthcoming books, In Search of Shiva and Walking with Nanak.

Limited-time offer: Big stories, small price. Keep independent media alive. Become a Scroll member today!

Our journalism is for everyone. But you can get special privileges by buying an annual Scroll Membership. Sign up today!