Dashrath Manjhi’s story was made for the big screen. He hit the headlines from Gehlaur village in Bihar’s Gaya district by single-handedly carving out a rough path over one of the slopes of a mountain between 1960 and 1982. Manjhi’s achievement, made possible by a combination of hammer, chisel, determination and obsessive dedication, significantly reduced the distance between Gehlaur and the Wazirganj town that lay on the other side of the slopes. Until he created the short-cut, Gehlaur’s villagers had to trek for over 70 kilometres around the mountain for water and food supplies. Manjhi reduced the distance to a few kilometers by carving out a 360-foot-long (110 m) path.

Manjhi’s one-man and dual-edged battle against nature and government apathy was reported first in the local press and then in the national media in the 1990s. It has inspired a documentary by Kundan Ranjan, another aborted non-fiction film, as well as Ketan Mehta’s upcoming biopic Manjhi The Mountain Man, which opens on August 21.

Ranjan’s The Man Who Moved the Mountain, produced by Films Division in 2011, contains possibly the last interview with Manjhi before he died on August 17, 2007. The documentary opens with a woman balancing a pot of water on her head and precariously making her way down the path that Manjhi carved over two decades. One of the reasons given by Manjhi for taming the mountain and doing the government’s work was the difficulty his wife faced in bringing water across the mountain. One day, her water pot broke, he tells Ranjan. “These mountains have been there since the beginning of time – imagine how any pots have broken over the years?”

Manjhi’s wife slipped from the mountain and died in 1959, possibly from injuries sustained during the fall. One night, Manjhi says, he heard a “voice from the sky” telling him to break the mountain, and he started attacking one small rock at a time with a hammer and a chisel (Manjhi obligingly recreates his actions in the documentary).

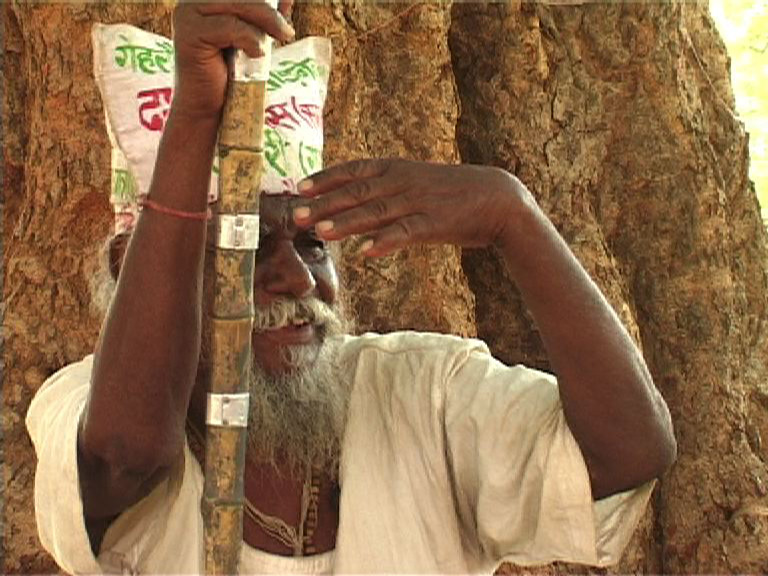

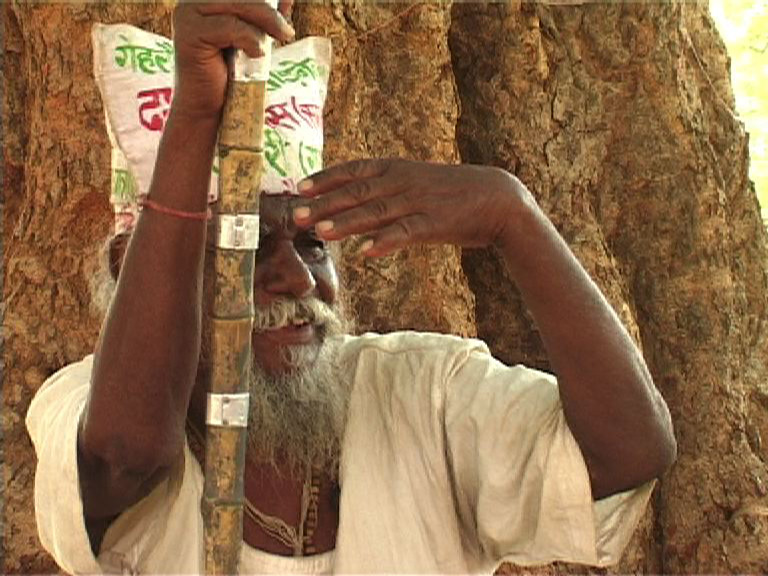

A still from Kundan Ranjan’s documentary.

Ranjan was a journalist with the Star News channel when he first heard of Manjhi. In 2007, he travelled to Gehlaur to meet the old man. “He was very moody, but also lovable,” Ranjan said. “He claimed that he did not understand what a documentary was – I told him that I was going to take his photograph and it would appear on television.”

It took Ranjan six months to persuade the famously stubborn self-made social worker to agree to an interview. “Every time I put on my camera, he would say, why are you taking my photo?” Ranjan recalled. “I eventually told him that it was costing me a lot of money to make these repeated trips to Gehlaur, and that is how he relented.”

Manjhi comes across as an unapologetic eccentric whose earthy and gnomic pronouncements conceal a deep understanding of the developmental problems faced by Gehlaur. “I’m the biggest fraud among frauds, the biggest idiot among idiots, I am the craziest among the crazies, the bravest of the brave,” he tells Ranjan.

It took the filmmaker two years to secure Films Division funding and complete the documentary, and Manjhi died just before the shooting was completed. The one-man road engineer might have been the subject of another documentary if Mumbai-based filmmaker Robina Gupta had managed to her own funding going. Gupta too was moved by newspaper reports about Manjhi, and she met him in early 2007.

“When I met him, the first thing I realised is that the mountain was just a barrier between him and the village, and he didn’t have any hatred towards it,” she said. Gupta relied on the interview, her own research and the writings of the Hindi writer Shaiwal on Manjhi. “I was looking for funds, but for whatever reason, things didn’t happen,” she said. Gupta cut a six-and-a-half minute short on her experience, which she has posted on YouTube.

Manjhi’s inspirational act has predictably inspired feature films too. The lead character of the 2011 Kannada road movie Olave Mandare meets a character modelled on Manjhi during his travels through India. Manish Jha, who directed Matrubhoomi, was also to have made a biopic, which fell through. Ketan Mehta’s version of the story, titled Manjhi The Mountain Man, would have been released earlier had it not been for a copyright battle with rival filmmaker Dhananjay Kapoor, who claimed that he was the sole owner of the rights to Manjhi’s story. Mehta eventually won his case, paving the way for his version of events.

The trailer depicts Manjhi, portrayed by Nawazuddin Siddiqui, as a man deeply in love with his wife, played by Radhika Apte. Just as the emperor Shah Jahan built the Taj Mahal for his beloved spouse Mumtaz after her death, Manjhi decided to burrow through the mountain as a tribute to his wife’s memory, suggests the trailer. In Ranjan’s documentary, Manjhi downplays the angle that his feelings for his wife were the sole motivation for his monumental efforts.

Manjhi’s story has acquired a folkloric quality over the years, and it is possible to have different explanations for his motivation, explained Vardaraj Swami, who did research for Manjhi The Mountain Man, contributed to its dialogue and is also an associate director on the project. “Especially after somebody has died, people explain the story in their own way and tend to exaggerate it and tell it differently,” Swami said. “It becomes like a folk tale, and it is challenging to find the true story. We too were initially confused – it is like the tales surrounding Chanakya and Kabir, where you realise that many of the writings attributed to them are interpolations and interventions made by their followers.”

There were a hundred drafts of the initial screenplay, which was finally polished by Mehta and Mahendar Jakhar with dialogue by Swami and Shahzad Ahmed. The writer Shaiwal is listed as a dialogue consultant in the credits.

“We finally took a straight path with the story – Manjhi broke the mountain for his wife, whom he loved immensely,” Swami said. “I have a line in the movie where Manjhi, replying to a question on where he gets the strength from, says, this is love, first for my wife and now for the mountain.”

Gehalur has improved considerably since Manjhi first decided to chip away at the mountain in 1960, in no small part due to the media attention. The village now has a school, electricity and hand pumps. “I have a line in the film that goes, don’t wait for a sign from God, it is possible that God is waiting for you to make the first move,” Swami said. “That line is meant to convey the fact that rather than waiting for spoon feeding, we the people need to take matters into our own hands. After all, Rabindranath Tagore said, ‘Ekla chalo re’, and nobody will do anything for you unless you do it yourself.” Nobody knew this better than Dashrath Manjhi.

Manjhi’s one-man and dual-edged battle against nature and government apathy was reported first in the local press and then in the national media in the 1990s. It has inspired a documentary by Kundan Ranjan, another aborted non-fiction film, as well as Ketan Mehta’s upcoming biopic Manjhi The Mountain Man, which opens on August 21.

Ranjan’s The Man Who Moved the Mountain, produced by Films Division in 2011, contains possibly the last interview with Manjhi before he died on August 17, 2007. The documentary opens with a woman balancing a pot of water on her head and precariously making her way down the path that Manjhi carved over two decades. One of the reasons given by Manjhi for taming the mountain and doing the government’s work was the difficulty his wife faced in bringing water across the mountain. One day, her water pot broke, he tells Ranjan. “These mountains have been there since the beginning of time – imagine how any pots have broken over the years?”

Manjhi’s wife slipped from the mountain and died in 1959, possibly from injuries sustained during the fall. One night, Manjhi says, he heard a “voice from the sky” telling him to break the mountain, and he started attacking one small rock at a time with a hammer and a chisel (Manjhi obligingly recreates his actions in the documentary).

A still from Kundan Ranjan’s documentary.

Ranjan was a journalist with the Star News channel when he first heard of Manjhi. In 2007, he travelled to Gehlaur to meet the old man. “He was very moody, but also lovable,” Ranjan said. “He claimed that he did not understand what a documentary was – I told him that I was going to take his photograph and it would appear on television.”

It took Ranjan six months to persuade the famously stubborn self-made social worker to agree to an interview. “Every time I put on my camera, he would say, why are you taking my photo?” Ranjan recalled. “I eventually told him that it was costing me a lot of money to make these repeated trips to Gehlaur, and that is how he relented.”

Manjhi comes across as an unapologetic eccentric whose earthy and gnomic pronouncements conceal a deep understanding of the developmental problems faced by Gehlaur. “I’m the biggest fraud among frauds, the biggest idiot among idiots, I am the craziest among the crazies, the bravest of the brave,” he tells Ranjan.

It took the filmmaker two years to secure Films Division funding and complete the documentary, and Manjhi died just before the shooting was completed. The one-man road engineer might have been the subject of another documentary if Mumbai-based filmmaker Robina Gupta had managed to her own funding going. Gupta too was moved by newspaper reports about Manjhi, and she met him in early 2007.

“When I met him, the first thing I realised is that the mountain was just a barrier between him and the village, and he didn’t have any hatred towards it,” she said. Gupta relied on the interview, her own research and the writings of the Hindi writer Shaiwal on Manjhi. “I was looking for funds, but for whatever reason, things didn’t happen,” she said. Gupta cut a six-and-a-half minute short on her experience, which she has posted on YouTube.

Manjhi’s inspirational act has predictably inspired feature films too. The lead character of the 2011 Kannada road movie Olave Mandare meets a character modelled on Manjhi during his travels through India. Manish Jha, who directed Matrubhoomi, was also to have made a biopic, which fell through. Ketan Mehta’s version of the story, titled Manjhi The Mountain Man, would have been released earlier had it not been for a copyright battle with rival filmmaker Dhananjay Kapoor, who claimed that he was the sole owner of the rights to Manjhi’s story. Mehta eventually won his case, paving the way for his version of events.

The trailer depicts Manjhi, portrayed by Nawazuddin Siddiqui, as a man deeply in love with his wife, played by Radhika Apte. Just as the emperor Shah Jahan built the Taj Mahal for his beloved spouse Mumtaz after her death, Manjhi decided to burrow through the mountain as a tribute to his wife’s memory, suggests the trailer. In Ranjan’s documentary, Manjhi downplays the angle that his feelings for his wife were the sole motivation for his monumental efforts.

Manjhi’s story has acquired a folkloric quality over the years, and it is possible to have different explanations for his motivation, explained Vardaraj Swami, who did research for Manjhi The Mountain Man, contributed to its dialogue and is also an associate director on the project. “Especially after somebody has died, people explain the story in their own way and tend to exaggerate it and tell it differently,” Swami said. “It becomes like a folk tale, and it is challenging to find the true story. We too were initially confused – it is like the tales surrounding Chanakya and Kabir, where you realise that many of the writings attributed to them are interpolations and interventions made by their followers.”

There were a hundred drafts of the initial screenplay, which was finally polished by Mehta and Mahendar Jakhar with dialogue by Swami and Shahzad Ahmed. The writer Shaiwal is listed as a dialogue consultant in the credits.

“We finally took a straight path with the story – Manjhi broke the mountain for his wife, whom he loved immensely,” Swami said. “I have a line in the movie where Manjhi, replying to a question on where he gets the strength from, says, this is love, first for my wife and now for the mountain.”

Gehalur has improved considerably since Manjhi first decided to chip away at the mountain in 1960, in no small part due to the media attention. The village now has a school, electricity and hand pumps. “I have a line in the film that goes, don’t wait for a sign from God, it is possible that God is waiting for you to make the first move,” Swami said. “That line is meant to convey the fact that rather than waiting for spoon feeding, we the people need to take matters into our own hands. After all, Rabindranath Tagore said, ‘Ekla chalo re’, and nobody will do anything for you unless you do it yourself.” Nobody knew this better than Dashrath Manjhi.

Limited-time offer: Big stories, small price. Keep independent media alive. Become a Scroll member today!

Our journalism is for everyone. But you can get special privileges by buying an annual Scroll Membership. Sign up today!