Western Indian Vegetable Products is an odd name for an $8 billion information technology consulting firm. But when Azim Premji, the founder's son took over the manufacturer of cooking oil, he transformed the scale and direction of the company, which had now abbreviated its name to Wipro.

More incongruity was to follow: Azim Premji has, till date, donated almost half his shareholdings in his very successful company towards philanthropy. On Wednesday, Premji gave away an additional 18% of his stake in Wipro, thus donating shares worth a total of Rs 53,000 crore towards charity. To put that in perspective, Rs 53,000 crore could finance the National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme for 18 months.

This sort of benevolence is rare in India and Premji is a lone wolf when it comes to big-ticket philanthropy in the country. It is a very rare occurrence for high net worth individuals to donate away their billions in India.

India’s Scrooges

Even as about 300 million Indians live in extreme poverty, the country does very well in giving rise to the ultra rich. India is the country with the third-largest number of billionaires in the world, lagging only China and the US. Moreover, not only is the number of billionaires high, the amount of wealth they control is rather obscene. The World Bank, for example, calls India’s billionaire wealth “exceptionally large”. The ratio of billionaire wealth to gross domestic product in India stood at 12% in 2012. In Vietnam, it was under 2%. This number has grown: it was only 1% in the mid-1990s, before the effects of liberalisation could take root.

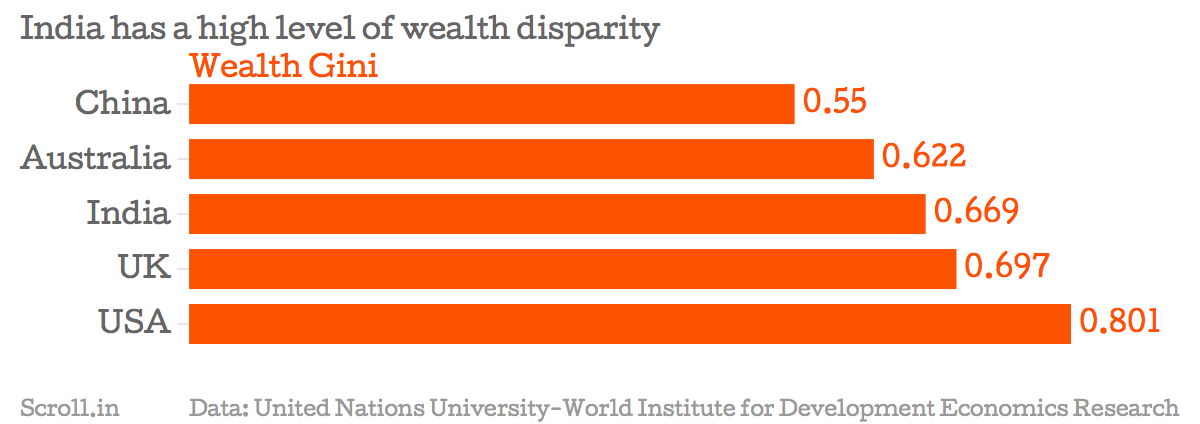

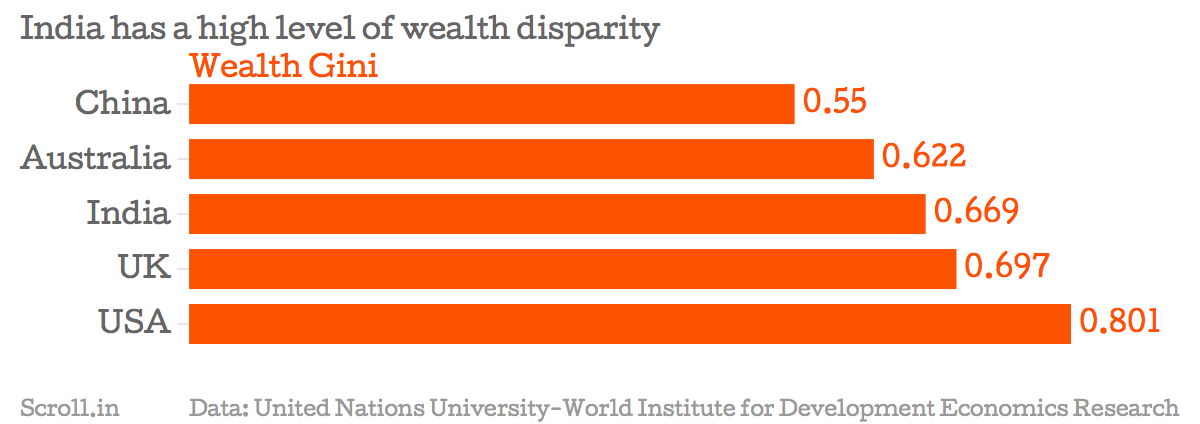

India, in fact, has wealth inequality that compares to highly developed nations such as the UK and Canada and is substantially more than China.

At the other end of the spectrum, India does significantly worse when it comes to human development. In preventing malnourishment of its children, for example, it lags behind sub-Saharan Africa. A baby born in India has a far greater chance of dying before its 5th birthday than if it had been born across the border in Bangladesh. India comes in at a lowly 135th on the Human Development Index rankings.

With such dismal amounts of poverty and large concentrations of wealth, India's ultra rich should have been on a philanthropic overdrive.

But they aren't.

According to consulting firm Bain and Company, philanthropy by Indians accounts for only 0.6% of GDP, far behind the 2.2% of the US. Leaving out topper Premji, everyone else in India performs abysmally. The country’s richest man, Mukesh Ambani, gave away only 0.4% of his wealth for philanthropic causes in 2014; only three Indians gave away more than Rs 1,000 crore.

US moneybags Bill Gates and Warren Buffett (worth over $150 billion combined), have announced that most of their wealth will be donated to the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. The two have even started a campaign to encourage the super rich to donate at least half of their wealth.

Even assuming these two to be outliers, your average billionaire in the West donates far more than Indian tycoons do. Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg donated 2.2% of his net worth in 2012 and George Soros donated 3.2%.

Indian POV

Is this a cultural thing? Is the worldview of a rich Indian somehow different from the worldview of a rich American?

In some ways, yes. Indians, for example, are major donators to religious causes, which would classically not be counted as “philanthropy” in the West. Data generated in 2014 by the consulting firm Bain, for example, shows that high net worth individuals in India give more to religious causes than education. And this involves some big bucks. If the famous Venkateswara temple at Tirupati, for example, donated its annual earnings, it would become the country’s second largest philanthropists.

However, is a comparison even justified, even taking into account the massive wealth of India’s billionaires?

Deval Sanghavi, cofounder of Dasra, a Mumbai-based strategic philanthropy foundation thinks that we “can’t compare India to the US since it is developed country. There was a very long timeframe for those individuals to become philanthropists.”

He added: “Wealth was created in India post-liberalisation and the concept of philanthropy in India is slowly taking root."

Getting better

Bain’s report on philanthropy in India backs this up. The proportion of Indians donating money went up from 14% in 2009 to 28% in 2013 (although this figure also includes religious donations).

Another more abrupt change has been mandated by the law: from 2014 onwards, every company with a net worth of Rs 500 crore or more or a turnover of at least R.1,000 crore or a net profit of Rs 5 crore in a year should spend 2% of their profit of the last three years on corporate social responsibility programmes.

Like most top down initiatives, however, this seems destined to fail. Aneel Karnani, a professor at the University of Michigan Ross School of Business, points out that since corporate social responsibility has been defined very loosely, firms will simply reclassify many of their profit-making activities as CSR with no real social welfare impact.

Actual impact, though, must be driven by broad-based changes in how India ultra rich look at giving back to the society that they made their wealth in (rather than, say, parking it in real estate, where it contributes nothing).

More incongruity was to follow: Azim Premji has, till date, donated almost half his shareholdings in his very successful company towards philanthropy. On Wednesday, Premji gave away an additional 18% of his stake in Wipro, thus donating shares worth a total of Rs 53,000 crore towards charity. To put that in perspective, Rs 53,000 crore could finance the National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme for 18 months.

This sort of benevolence is rare in India and Premji is a lone wolf when it comes to big-ticket philanthropy in the country. It is a very rare occurrence for high net worth individuals to donate away their billions in India.

India’s Scrooges

Even as about 300 million Indians live in extreme poverty, the country does very well in giving rise to the ultra rich. India is the country with the third-largest number of billionaires in the world, lagging only China and the US. Moreover, not only is the number of billionaires high, the amount of wealth they control is rather obscene. The World Bank, for example, calls India’s billionaire wealth “exceptionally large”. The ratio of billionaire wealth to gross domestic product in India stood at 12% in 2012. In Vietnam, it was under 2%. This number has grown: it was only 1% in the mid-1990s, before the effects of liberalisation could take root.

India, in fact, has wealth inequality that compares to highly developed nations such as the UK and Canada and is substantially more than China.

At the other end of the spectrum, India does significantly worse when it comes to human development. In preventing malnourishment of its children, for example, it lags behind sub-Saharan Africa. A baby born in India has a far greater chance of dying before its 5th birthday than if it had been born across the border in Bangladesh. India comes in at a lowly 135th on the Human Development Index rankings.

With such dismal amounts of poverty and large concentrations of wealth, India's ultra rich should have been on a philanthropic overdrive.

But they aren't.

According to consulting firm Bain and Company, philanthropy by Indians accounts for only 0.6% of GDP, far behind the 2.2% of the US. Leaving out topper Premji, everyone else in India performs abysmally. The country’s richest man, Mukesh Ambani, gave away only 0.4% of his wealth for philanthropic causes in 2014; only three Indians gave away more than Rs 1,000 crore.

US moneybags Bill Gates and Warren Buffett (worth over $150 billion combined), have announced that most of their wealth will be donated to the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. The two have even started a campaign to encourage the super rich to donate at least half of their wealth.

Even assuming these two to be outliers, your average billionaire in the West donates far more than Indian tycoons do. Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg donated 2.2% of his net worth in 2012 and George Soros donated 3.2%.

Indian POV

Is this a cultural thing? Is the worldview of a rich Indian somehow different from the worldview of a rich American?

In some ways, yes. Indians, for example, are major donators to religious causes, which would classically not be counted as “philanthropy” in the West. Data generated in 2014 by the consulting firm Bain, for example, shows that high net worth individuals in India give more to religious causes than education. And this involves some big bucks. If the famous Venkateswara temple at Tirupati, for example, donated its annual earnings, it would become the country’s second largest philanthropists.

However, is a comparison even justified, even taking into account the massive wealth of India’s billionaires?

Deval Sanghavi, cofounder of Dasra, a Mumbai-based strategic philanthropy foundation thinks that we “can’t compare India to the US since it is developed country. There was a very long timeframe for those individuals to become philanthropists.”

He added: “Wealth was created in India post-liberalisation and the concept of philanthropy in India is slowly taking root."

Getting better

Bain’s report on philanthropy in India backs this up. The proportion of Indians donating money went up from 14% in 2009 to 28% in 2013 (although this figure also includes religious donations).

Another more abrupt change has been mandated by the law: from 2014 onwards, every company with a net worth of Rs 500 crore or more or a turnover of at least R.1,000 crore or a net profit of Rs 5 crore in a year should spend 2% of their profit of the last three years on corporate social responsibility programmes.

Like most top down initiatives, however, this seems destined to fail. Aneel Karnani, a professor at the University of Michigan Ross School of Business, points out that since corporate social responsibility has been defined very loosely, firms will simply reclassify many of their profit-making activities as CSR with no real social welfare impact.

Actual impact, though, must be driven by broad-based changes in how India ultra rich look at giving back to the society that they made their wealth in (rather than, say, parking it in real estate, where it contributes nothing).

Buy an annual Scroll Membership to support independent journalism and get special benefits.

Our journalism is for everyone. But you can get special privileges by buying an annual Scroll Membership. Sign up today!