A staggering 52% of children in Madhya Pradesh are malnourished but chief minister Shivraj Singh Chouhan has flatly refused to provide them with a key source of protein they could use: eggs. He made his stand clear recently while turning down a proposal from the state’s own Women and Child Development department to serve eggs on a pilot basis in the anganwadis of three tribal districts.

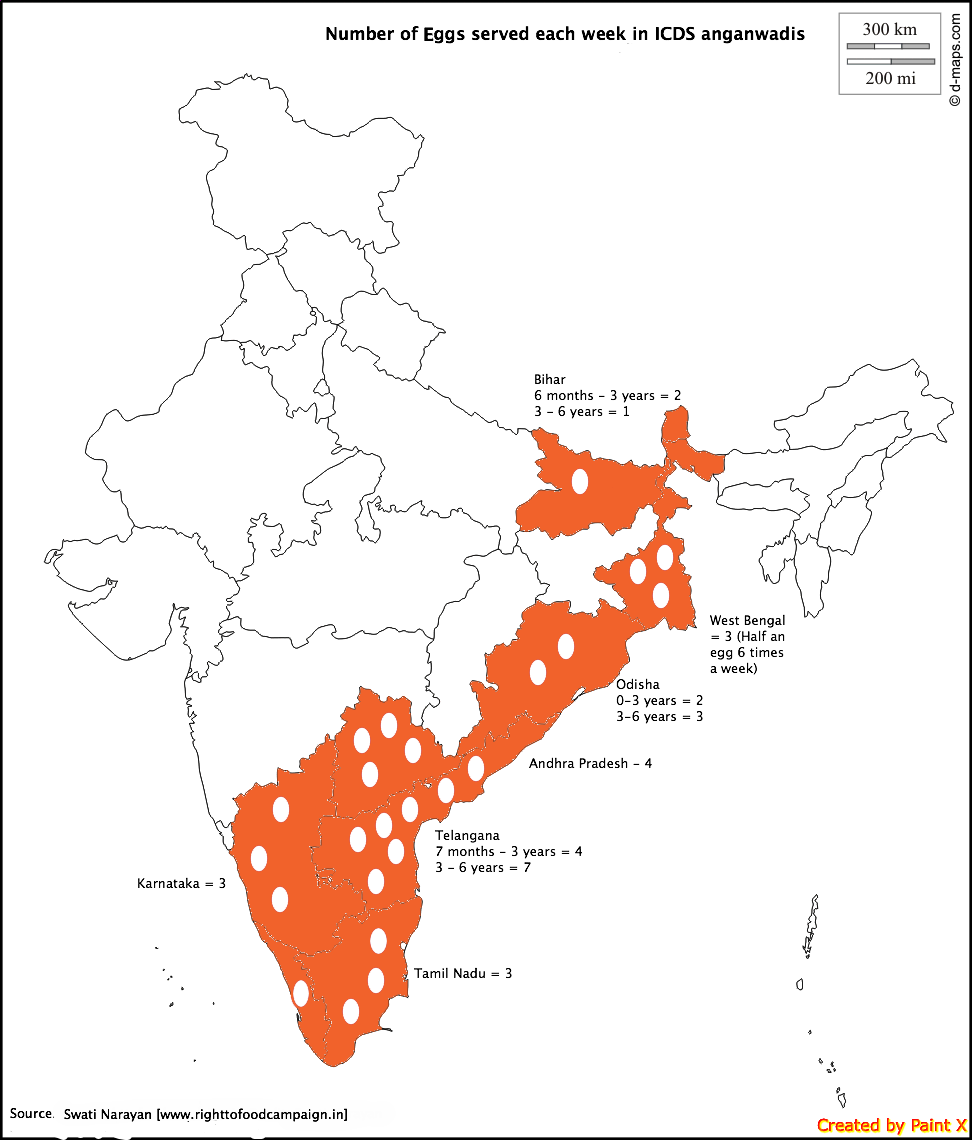

At least 15 states across the country provide eggs to under-nourished children – some only in the Integrated Child Development Scheme anganwadis, some in the midday meal scheme for schools, and some states in both schemes.

Recent maps released by the Right to Food Campaign reveal that provision of eggs for state government run nutrition schemes is prevalent across large swathes of eastern and southern India.

Under the ICDS programme, designed to improve nutrition among pregnant women, lactating mothers and children up to three years of age, eggs are provided at anganwadis in at least nine states.

In West Bengal, for instance, provides three eggs a week to each child or mother approaching an anganwadi – half an egg every day for six days a week. Bihar and Odisha provide eggs twice a week, Tamil Nadu and Karnataka serve eggs thrice a week while Andhra Pradesh and Telangana have eggs on their menu four times a week.

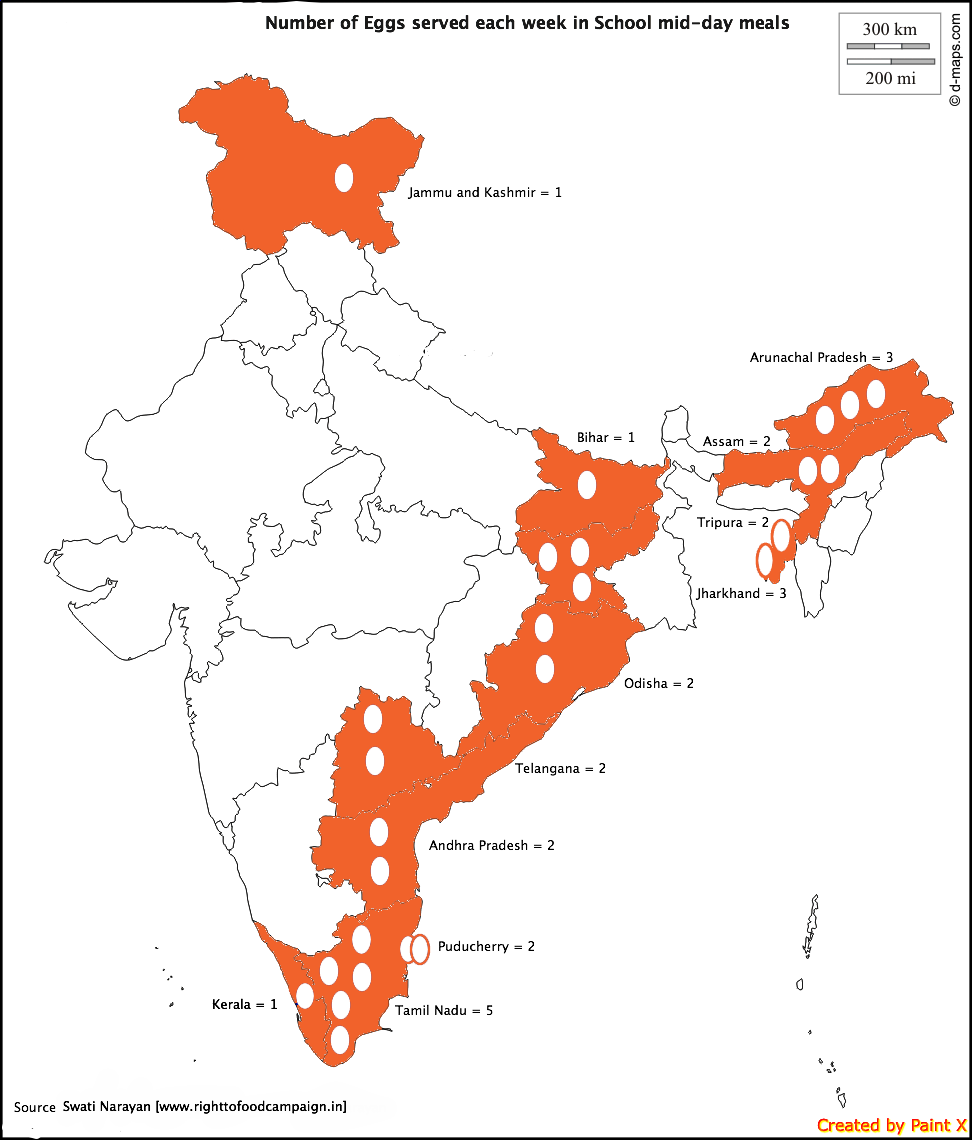

Eggs are more popular in midday meal programmes, which serve one hot cooked meals to children aged three to six in schools. At least 12 states include eggs in these meals, including Jammu and Kashmir, Jharkhand, Arunachal Pradesh, Assam and Tripura. Tamil Nadu is the most generous of the lot, providing five eggs a week to school children.

The anti-egg lobby

As is evident from the maps, most states across northern and western India do not provide eggs in its nutrition programmes. In some Bharatiya Janata Party-run states in particular, however, attempts to introduce eggs on the menu have been consistently blocked by groups opposing non-vegetarian food. But the beneficiaries of these schemes, say activists, are often tribal or Dalit populations who do not practice the norms of vegetarianism being imposed on them.

In Madhya Pradesh, the vegetarian chief minister has often publicly emphasised that eggs will never be served in the state’s schemes for malnourished children. A prominent group pressurising and influencing the government is the Jain community, whose representatives have claimed non-vegetarian food kills “sensitivity” in children.

“For at least four years, we have been trying to convince the Hindutva-Jain groups about the benefits of eggs, by giving them facts and figures and logical arguments,” said Rolly Shivhare, a Right to Food Campaign activist in Madhya Pradesh.

Eggs are known to have high protein-levels that are easily digestible by severely and acutely malnourished children. Madhya Pradesh has at least eight lakh such children in its rural and tribal belts, say activists. Most of these populations have always been non-vegetarian consumers of eggs and meat.

In fact, a 2006 survey of food habits in India revealed that 60% of Indians are non-vegetarian, while vegetarianism dominates mainly in the upper castes.

“The problem is that the upper-caste groups who are opposed to eggs in nutrition schemes are not the people who would ever need to avail of these schemes, but they are the ones who influence government policies based on their religious ideologies,” said Sachin Jain, another Right to Food activist based in Bhopal. The communities who benefit from nutrition schemes don’t share these ideologies, Jain points out. “Meanwhile, those who are well-off don’t even take any responsibility to tackle malnutrition in the state.”

In other states

Attempts to introduce eggs in anganwadi and midday meal programmes in several other states have also proved controversial.

In Chhattisgarh, for instance, eggs are being provided to young children and malnourished mothers at fulwaris in tribal districts like Surguja. Fulwaris serve as crèches for infants that are run by their own mothers from each village, and the mothers themselves take turns to cook the meals.

But fulwaris are not part of any state government nutrition programme: they are run by the communities themselves at the village level, and the funds for the food come from the district administration.

In the state-run programmes, right to food activists have been fighting a losing battle for several years. In 2005, the state had introduced eggs on its midday meal menu for school children. But in 2013, the central government published a review report of the midday meal scheme in Chhattisgarh, which states that the instructions to include eggs in meals was no longer in force. This led to several districts knocking eggs off their midday meal menu.

“Eggs are of critical importance in a state with high child under-nutrition, especially in tribal areas,” the report said, while recommending that Chhattisgarh provide eggs to school children again. The suggestion has not been taken up.

“A couple of years ago, [chief minister] Raman Singh reportedly said in a public meeting in Surguja that tribal children need to be fed eggs,” said a Chhattisgarh-based food activist who did not wish to be named. “But he has not taken it up at the policy level as it is obvious he does not want to be unpopular with his Hindutva bosses.”

The case of Karnataka

In states like Rajasthan and Karnataka, provision of midday meals in schools has been taken up by NGOs like Akshay Patra, who insist on serving a strictly vegetarian fare to children.

While Karnataka’s anganwadis do serve eggs under the ICDS programme, its midday meal scheme has been heavily influenced by this vegetarian lobby, which includes Akshay Patra and the religious organisation ISKCON Food Relief Foundation.

“There have been plans to introduce eggs in midday meals in Karnataka, but that has been blocked,” said Clifton D’Rozario, a Bangalore-based lawyer who has worked actively on malnutrition and is also the Supreme Court commissioner’s advisor on Right to Food.

In 2013, the ISKCON Food Relief Foundation, while being probed by a parliamentary committee, had stated that if beneficiaries of the midday meal schemes wanted eggs, they could get them from elsewhere. Nothing seems to have changed since the Congress came into power in Karnataka in May 2013. D'Rozario, for instance, had submitted a report to the previous, BJP government in March 2013, recommending the inclusion of eggs in midday meals. "The report has been ignored ever since. I don't think the Congress government has given much thought to the issue," said D'Rozario.

“These notions, however, are quite ridiculous and a complete misunderstanding of vegetarianism,” said economist Jean Drèze, who points out that none of the states that serve eggs in their schemes impose it as compulsory. “No one can dictate what other people should or shouldn’t eat.”

At least 15 states across the country provide eggs to under-nourished children – some only in the Integrated Child Development Scheme anganwadis, some in the midday meal scheme for schools, and some states in both schemes.

Recent maps released by the Right to Food Campaign reveal that provision of eggs for state government run nutrition schemes is prevalent across large swathes of eastern and southern India.

Under the ICDS programme, designed to improve nutrition among pregnant women, lactating mothers and children up to three years of age, eggs are provided at anganwadis in at least nine states.

In West Bengal, for instance, provides three eggs a week to each child or mother approaching an anganwadi – half an egg every day for six days a week. Bihar and Odisha provide eggs twice a week, Tamil Nadu and Karnataka serve eggs thrice a week while Andhra Pradesh and Telangana have eggs on their menu four times a week.

Eggs are more popular in midday meal programmes, which serve one hot cooked meals to children aged three to six in schools. At least 12 states include eggs in these meals, including Jammu and Kashmir, Jharkhand, Arunachal Pradesh, Assam and Tripura. Tamil Nadu is the most generous of the lot, providing five eggs a week to school children.

The anti-egg lobby

As is evident from the maps, most states across northern and western India do not provide eggs in its nutrition programmes. In some Bharatiya Janata Party-run states in particular, however, attempts to introduce eggs on the menu have been consistently blocked by groups opposing non-vegetarian food. But the beneficiaries of these schemes, say activists, are often tribal or Dalit populations who do not practice the norms of vegetarianism being imposed on them.

In Madhya Pradesh, the vegetarian chief minister has often publicly emphasised that eggs will never be served in the state’s schemes for malnourished children. A prominent group pressurising and influencing the government is the Jain community, whose representatives have claimed non-vegetarian food kills “sensitivity” in children.

“For at least four years, we have been trying to convince the Hindutva-Jain groups about the benefits of eggs, by giving them facts and figures and logical arguments,” said Rolly Shivhare, a Right to Food Campaign activist in Madhya Pradesh.

Eggs are known to have high protein-levels that are easily digestible by severely and acutely malnourished children. Madhya Pradesh has at least eight lakh such children in its rural and tribal belts, say activists. Most of these populations have always been non-vegetarian consumers of eggs and meat.

In fact, a 2006 survey of food habits in India revealed that 60% of Indians are non-vegetarian, while vegetarianism dominates mainly in the upper castes.

“The problem is that the upper-caste groups who are opposed to eggs in nutrition schemes are not the people who would ever need to avail of these schemes, but they are the ones who influence government policies based on their religious ideologies,” said Sachin Jain, another Right to Food activist based in Bhopal. The communities who benefit from nutrition schemes don’t share these ideologies, Jain points out. “Meanwhile, those who are well-off don’t even take any responsibility to tackle malnutrition in the state.”

In other states

Attempts to introduce eggs in anganwadi and midday meal programmes in several other states have also proved controversial.

In Chhattisgarh, for instance, eggs are being provided to young children and malnourished mothers at fulwaris in tribal districts like Surguja. Fulwaris serve as crèches for infants that are run by their own mothers from each village, and the mothers themselves take turns to cook the meals.

But fulwaris are not part of any state government nutrition programme: they are run by the communities themselves at the village level, and the funds for the food come from the district administration.

In the state-run programmes, right to food activists have been fighting a losing battle for several years. In 2005, the state had introduced eggs on its midday meal menu for school children. But in 2013, the central government published a review report of the midday meal scheme in Chhattisgarh, which states that the instructions to include eggs in meals was no longer in force. This led to several districts knocking eggs off their midday meal menu.

“Eggs are of critical importance in a state with high child under-nutrition, especially in tribal areas,” the report said, while recommending that Chhattisgarh provide eggs to school children again. The suggestion has not been taken up.

“A couple of years ago, [chief minister] Raman Singh reportedly said in a public meeting in Surguja that tribal children need to be fed eggs,” said a Chhattisgarh-based food activist who did not wish to be named. “But he has not taken it up at the policy level as it is obvious he does not want to be unpopular with his Hindutva bosses.”

The case of Karnataka

In states like Rajasthan and Karnataka, provision of midday meals in schools has been taken up by NGOs like Akshay Patra, who insist on serving a strictly vegetarian fare to children.

While Karnataka’s anganwadis do serve eggs under the ICDS programme, its midday meal scheme has been heavily influenced by this vegetarian lobby, which includes Akshay Patra and the religious organisation ISKCON Food Relief Foundation.

“There have been plans to introduce eggs in midday meals in Karnataka, but that has been blocked,” said Clifton D’Rozario, a Bangalore-based lawyer who has worked actively on malnutrition and is also the Supreme Court commissioner’s advisor on Right to Food.

In 2013, the ISKCON Food Relief Foundation, while being probed by a parliamentary committee, had stated that if beneficiaries of the midday meal schemes wanted eggs, they could get them from elsewhere. Nothing seems to have changed since the Congress came into power in Karnataka in May 2013. D'Rozario, for instance, had submitted a report to the previous, BJP government in March 2013, recommending the inclusion of eggs in midday meals. "The report has been ignored ever since. I don't think the Congress government has given much thought to the issue," said D'Rozario.

“These notions, however, are quite ridiculous and a complete misunderstanding of vegetarianism,” said economist Jean Drèze, who points out that none of the states that serve eggs in their schemes impose it as compulsory. “No one can dictate what other people should or shouldn’t eat.”

Buy an annual Scroll Membership to support independent journalism and get special benefits.

Our journalism is for everyone. But you can get special privileges by buying an annual Scroll Membership. Sign up today!