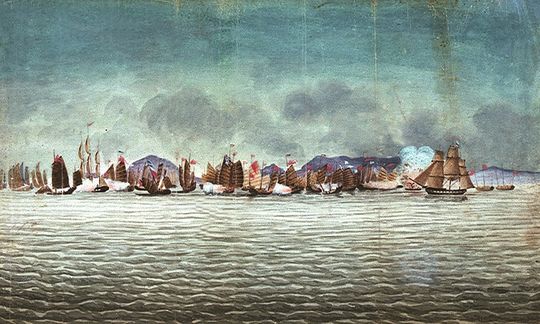

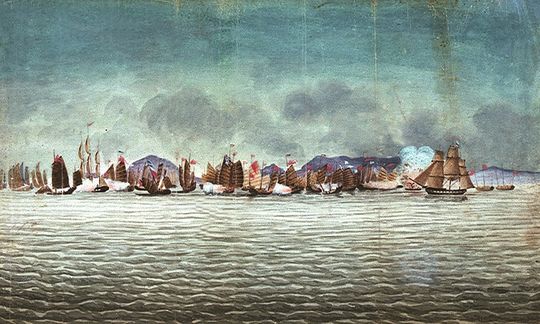

Kesri, no less than the younger sepoys, was awed by the sight that greeted them when the Hind sailed into Singapore’s outer harbour. Six warships were riding at anchor there, one of them a majestic triple-decked man-o’-war.

The transport and supply vessels were moored at a slight distance from the warships. There were no fewer than twelve of them, their decks aswarm with red-coated soldiers and sepoys. The Hind dropped anchor right next to the troopship that was carrying their brother unit – the other company of Bengal Volunteers. The sepoys gathered on deck to exchange shouted greetings.

Looking around the harbour, Kesri saw that the Royal Irish Regiment had already arrived, as had the 49th and the left wing of the Cameronians. Only the 37th Madras Regiment was still to come.

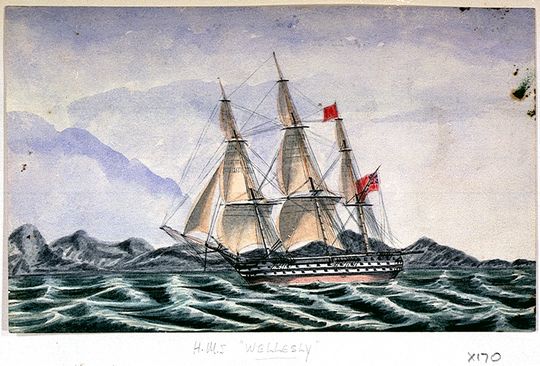

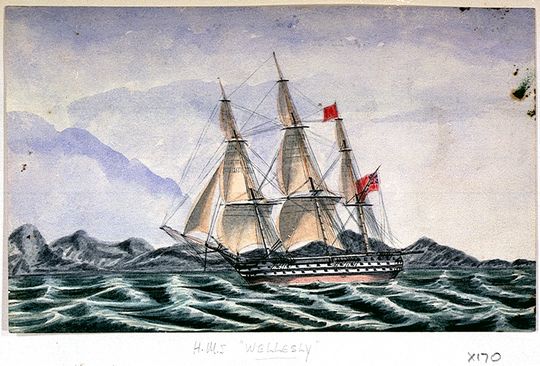

Later that day Captain Mee summoned Kesri to the quarter-deck for his daily report on the conditions below. Their business was quickly dispatched and afterwards the captain identified the warships for Kesri, rattling off their names one by one: that over there was the eighteen-gun Cruiser, and there was the ten-gun Algerine riding beside two twenty-eight-gun frigates, Conway and Alligator. And towering over them all was the man-o’-war, Wellesley: she was a ship-of-the-line, said Captain Mee, armed with no fewer than seventy-four guns.

The Wellesley was the tallest sailing vessel that Kesri had ever set eyes on. He assumed that she was, if not the most powerful vessel in the Royal Navy, then certainly of their number. But Captain Mee explained that by the standards of the Royal Navy the Wellesley was but a vessel of medium size, rated as a warship of the third class. Much the same could be said of the fleet itself, the captain added – although large for Asian waters, it was small by the standards of the Royal Navy, which frequently assembled armadas of fifty warships or more.

Kesri was both chastened and reassured to learn of this. He understood from the captain’s tone that from the British perspective this expedition was a relatively minor venture and that they were completely confident of achieving their objectives. This was just as well, as far as Kesri was concerned. Heroics were of no interest to him – he had wounds enough to show for his years in service, and all that concerned him now was getting himself and his men safely back to their villages.

Later in the day Captain Mee and his subalterns went off in a longboat, to attend a meeting on the Wellesley. When they returned, several hours later, Captain Mee summoned Kesri to his stateroom for a briefing.

There had been some major changes in the expedition’s chain of command, the captain told him. Admiral Frederick Maitland, who was to have commanded the expedition, had taken ill and another officer had been given his post – Rear-Admiral George Elliot, who, as it happened, was the cousin of the British Plenipotentiary in China, Captain Charles Elliot.

Rear-Admiral Elliot was on his way from Cape Town and would join the expedition later; until then Commodore Sir Gordon Bremer would be in command and Colonel Burrell would be in charge of operational details. The colonel had already taken some important decisions regarding the force’s stay in Singapore. One of them was that the soldiers and sepoys would remain on their ships, through the duration of the stay.

Kesri was disappointed to hear this, for he had been hoping to spend a few days on dry land. ‘Why so, sir?’

‘Singapore is a small colony, havildar, not yet twenty years old,’ said Captain Mee. ‘To set up a camp large enough to hold all of us would be difficult because the island’s forests are very dense. And there are tigers too – a couple of men were killed just this week, on the edge of town.’

‘So how long will we be here, sir?’

‘There’s no telling,’ said the captain. ‘A third or more of the force is still to arrive. I’d say it’ll take another couple of weeks, at the very least.’

‘Will there be liberty, sir? Shore leave?’

The captain shot him a glance. ‘It wouldn’t be much use to you, havildar,’ he said with a wry smile. ‘If you’re thinking of bawdy-baskets, you can put that out of your mind. Women are as scarce as diamonds in Singapore – the knocking-shops are full of travesties so you’d probably end up with a molly-dan. And if back- gammoning isn’t to your taste, then the only other diversion is chasing the yinyan.’

‘So what will the men do here, sir, for two weeks?’

The captain laughed. ‘Drills, havildar, drills! Boat drills, attack drills, bayonet drills, rocket drills. Don’t worry – there’ll be plenty to do.’

Excerpted with permission from Flood of Fire, Amitav Ghosh, Penguin Books India.

The transport and supply vessels were moored at a slight distance from the warships. There were no fewer than twelve of them, their decks aswarm with red-coated soldiers and sepoys. The Hind dropped anchor right next to the troopship that was carrying their brother unit – the other company of Bengal Volunteers. The sepoys gathered on deck to exchange shouted greetings.

Looking around the harbour, Kesri saw that the Royal Irish Regiment had already arrived, as had the 49th and the left wing of the Cameronians. Only the 37th Madras Regiment was still to come.

Later that day Captain Mee summoned Kesri to the quarter-deck for his daily report on the conditions below. Their business was quickly dispatched and afterwards the captain identified the warships for Kesri, rattling off their names one by one: that over there was the eighteen-gun Cruiser, and there was the ten-gun Algerine riding beside two twenty-eight-gun frigates, Conway and Alligator. And towering over them all was the man-o’-war, Wellesley: she was a ship-of-the-line, said Captain Mee, armed with no fewer than seventy-four guns.

The Wellesley was the tallest sailing vessel that Kesri had ever set eyes on. He assumed that she was, if not the most powerful vessel in the Royal Navy, then certainly of their number. But Captain Mee explained that by the standards of the Royal Navy the Wellesley was but a vessel of medium size, rated as a warship of the third class. Much the same could be said of the fleet itself, the captain added – although large for Asian waters, it was small by the standards of the Royal Navy, which frequently assembled armadas of fifty warships or more.

Kesri was both chastened and reassured to learn of this. He understood from the captain’s tone that from the British perspective this expedition was a relatively minor venture and that they were completely confident of achieving their objectives. This was just as well, as far as Kesri was concerned. Heroics were of no interest to him – he had wounds enough to show for his years in service, and all that concerned him now was getting himself and his men safely back to their villages.

Later in the day Captain Mee and his subalterns went off in a longboat, to attend a meeting on the Wellesley. When they returned, several hours later, Captain Mee summoned Kesri to his stateroom for a briefing.

There had been some major changes in the expedition’s chain of command, the captain told him. Admiral Frederick Maitland, who was to have commanded the expedition, had taken ill and another officer had been given his post – Rear-Admiral George Elliot, who, as it happened, was the cousin of the British Plenipotentiary in China, Captain Charles Elliot.

Rear-Admiral Elliot was on his way from Cape Town and would join the expedition later; until then Commodore Sir Gordon Bremer would be in command and Colonel Burrell would be in charge of operational details. The colonel had already taken some important decisions regarding the force’s stay in Singapore. One of them was that the soldiers and sepoys would remain on their ships, through the duration of the stay.

Kesri was disappointed to hear this, for he had been hoping to spend a few days on dry land. ‘Why so, sir?’

‘Singapore is a small colony, havildar, not yet twenty years old,’ said Captain Mee. ‘To set up a camp large enough to hold all of us would be difficult because the island’s forests are very dense. And there are tigers too – a couple of men were killed just this week, on the edge of town.’

‘So how long will we be here, sir?’

‘There’s no telling,’ said the captain. ‘A third or more of the force is still to arrive. I’d say it’ll take another couple of weeks, at the very least.’

‘Will there be liberty, sir? Shore leave?’

The captain shot him a glance. ‘It wouldn’t be much use to you, havildar,’ he said with a wry smile. ‘If you’re thinking of bawdy-baskets, you can put that out of your mind. Women are as scarce as diamonds in Singapore – the knocking-shops are full of travesties so you’d probably end up with a molly-dan. And if back- gammoning isn’t to your taste, then the only other diversion is chasing the yinyan.’

‘So what will the men do here, sir, for two weeks?’

The captain laughed. ‘Drills, havildar, drills! Boat drills, attack drills, bayonet drills, rocket drills. Don’t worry – there’ll be plenty to do.’

Excerpted with permission from Flood of Fire, Amitav Ghosh, Penguin Books India.

Limited-time offer: Big stories, small price. Keep independent media alive. Become a Scroll member today!

Our journalism is for everyone. But you can get special privileges by buying an annual Scroll Membership. Sign up today!