I vividly remember my great-uncle Ottone Menato riding his bicycle through the main road of the sleepy city where I grew up in northern Italy. He was in his late 60s, still lean, always sporting a mountain tan, and ever ready to flash that charismatic smile that lured you towards him and his distinct aura of a man with a past.

He was a known Alpinist who had given colourful names to valleys and rock-climbing routes. He was a traveller and a prized poet. But mostly, he was a novelist, a vocation I share with him. His most famous novel contained the secret of my fascination for him: a fictionalised tale of his six years in British prison camps during World War II – first and briefly in Geneifa, Egypt, but mostly in Bangalore and Yol camps in India.

At first it isn’t clear why he called the novel Latin Lovers. There’s hardly a female figure in the book, except for a poor local woman who sells her body to some of the prisoners and the letter-writing wife of protagonist Diego Taranto, captain of the Alpini mountain corps.

The title is borrowed from a conversation on the novel’s last page. Diego is smashing rocks, mostly to vent his rage at still being in captivity after six years. A Dravidian clerk, celebrating V Day, approaches him and smilingly tells him that the war is over and the prisoners of war can finally go home. Isn’t he happy? Diego ignores him rudely. The clerk insists and then deals the crushing blow: “Italians… sorry… yes, Italians good! Good people, good workers, good musicians, good singers, famed Latin lovers, yes… sorry… but not good fighters.” Diego yells to be left alone.

It is to fight this attitude that Diego (like his alter ego, my great-uncle Otto) kept trying to escape, risking his life in the process. He wants to prove that he is better than the demeaning stereotype.

The conversation with the clerk is a poignant ending for a book that begins with the capture of many badly equipped Italians in Northern Africa. Diego is one of them. He escapes from the Egyptian prison and manages to survive for weeks, before being captured and shipped on a long voyage across the Indian Ocean to Bombay.

It is possible to still find footage online documenting four Italian generals and hundreds of Italian POWs landing at Bombay Harbour and parading down the city’s boulevard. From Bombay they were quickly packed off in a suffocating train ride to a prison camp in Bangalore.

The prison camp life was secretly documented by POW Lido Saltamartini in 2,000 photographs with a clandestine camera he built himself. He assembled it out of a Waltham’s cigarettes metallic box, tin ripped from a McLeans toothpaste tube and a candle borrowed from the chaplain, plus a soy sausage wrapper and a 4mm lens. Now 100 years old, he has just turned his collection into a photographic book, whose sales benefit deaf-mute children.

Just as my great-uncle Otto coped with his captivity by writing a novel, Raffaello Paganini, a Navy officer, survived by inking a series of portraits and paysages on toilet paper. Paganini, in a letter to his parents, wrote about “the many Indians, so many Indians who, when we walked out of the train, looked at us marching by, but did not laugh – instead they stared with serious and sad expressions on their faces. They seemed so beautiful to me, with their colourful clothes that looked like flowers”.

This is another charming aspect of the novel and of my great-uncle’s difficult, yet intense, experiences in India 70 years ago. As his fictional alter ego Diego prepares for his many escapes (getting regularly captured), we see an India of the Partition and of the Independence years, where most of the locals encountered do not treat the Italian prisoners on the run as hostile but as an exotic guest. Few are the episodes in which the runaways are denounced to the authorities. And this may be due to the fact that the escaping Italian officers in Latin Lovers strictly abide to the self-imposed rule of never stealing food, but always paying for provisions.

In Latin Lovers, after Diego has made a couple of failed efforts to escape from the Bangalore prison, news comes in of Japanese troops moving towards Singapore. This prompts the British command to send POW officers north to the Young Officers on Leave camp at the foot of the Himalayas. There’s plenty of literature on the Yol camp, 10 km west of Dharamsala. In the last decade, two other Italian novels have been published on the lives of the 12,000 Italian soldiers sent up there.

Yol was an impressive prison camp with hundreds of barracks on a 770-acre property. While the relationship with the locals was generally good, not all was rosy. Prisoners were granted freedom to explore the mountains and go on treks but to help map heights. As a result of this, one summitted mountain was named “Cima Italia” or Italian peak. In another instance, an Italian officer who repeatedly refused to stop singing a Fascist song in honour of the birth of Rome was shot dead and received, posthumously, the Medal of Honour. Killed for singing: so Italian.

There are still many stories in Yol of the lifestyles of Italian POWs. Some left behind their dogs with Italian names, Paletto (little stick), some cultivated vegetable gardens and distilled Grappa liquor, some would visit their Indian friends in the village, cook food and bring medicines.

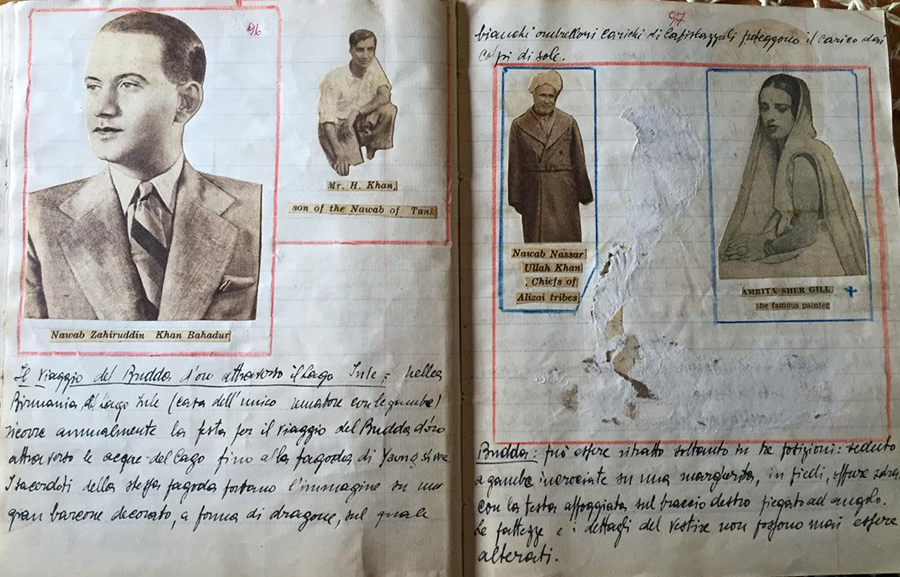

This is also what was happening to the fictional Diego Taranto, who kept trying to escape nevertheless. In Latin Lovers, my great-uncle insisted that it was an officer’s duty to continue attempting escape: “it was the only way a prisoner could keep the enemy busy”. That might be, but Otto was also attracted by the magnetism of the mountains and of the ascent. He completed many climbs, meticulously documenting them in his drawing book, measuring altitudes, trying to let time pass, until he finally returned to his family and his country where he received the Cross of War medal. He died at 82, in my hometown.

Yol still stands. From August to October 1947, 12,000 Muslims were kept there on their way to Pakistan. From 1949 to 1952, it became a refugee camp for Kashmiri migrants. Then it was turned into military barracks, housing the Rising Star, the youngest battalion of the Indian Army.

It is still possible to visit it. Even to sleep in one of the barracks. People still report finding old rusted cans used by the Italians. They are a memento of a painful chapter in history. A chapter my great-uncle tried to express by writing a novel to cope with a trauma, and transform a memory into something useful for himself and for others.

He was a known Alpinist who had given colourful names to valleys and rock-climbing routes. He was a traveller and a prized poet. But mostly, he was a novelist, a vocation I share with him. His most famous novel contained the secret of my fascination for him: a fictionalised tale of his six years in British prison camps during World War II – first and briefly in Geneifa, Egypt, but mostly in Bangalore and Yol camps in India.

At first it isn’t clear why he called the novel Latin Lovers. There’s hardly a female figure in the book, except for a poor local woman who sells her body to some of the prisoners and the letter-writing wife of protagonist Diego Taranto, captain of the Alpini mountain corps.

The title is borrowed from a conversation on the novel’s last page. Diego is smashing rocks, mostly to vent his rage at still being in captivity after six years. A Dravidian clerk, celebrating V Day, approaches him and smilingly tells him that the war is over and the prisoners of war can finally go home. Isn’t he happy? Diego ignores him rudely. The clerk insists and then deals the crushing blow: “Italians… sorry… yes, Italians good! Good people, good workers, good musicians, good singers, famed Latin lovers, yes… sorry… but not good fighters.” Diego yells to be left alone.

It is to fight this attitude that Diego (like his alter ego, my great-uncle Otto) kept trying to escape, risking his life in the process. He wants to prove that he is better than the demeaning stereotype.

The conversation with the clerk is a poignant ending for a book that begins with the capture of many badly equipped Italians in Northern Africa. Diego is one of them. He escapes from the Egyptian prison and manages to survive for weeks, before being captured and shipped on a long voyage across the Indian Ocean to Bombay.

It is possible to still find footage online documenting four Italian generals and hundreds of Italian POWs landing at Bombay Harbour and parading down the city’s boulevard. From Bombay they were quickly packed off in a suffocating train ride to a prison camp in Bangalore.

The prison camp life was secretly documented by POW Lido Saltamartini in 2,000 photographs with a clandestine camera he built himself. He assembled it out of a Waltham’s cigarettes metallic box, tin ripped from a McLeans toothpaste tube and a candle borrowed from the chaplain, plus a soy sausage wrapper and a 4mm lens. Now 100 years old, he has just turned his collection into a photographic book, whose sales benefit deaf-mute children.

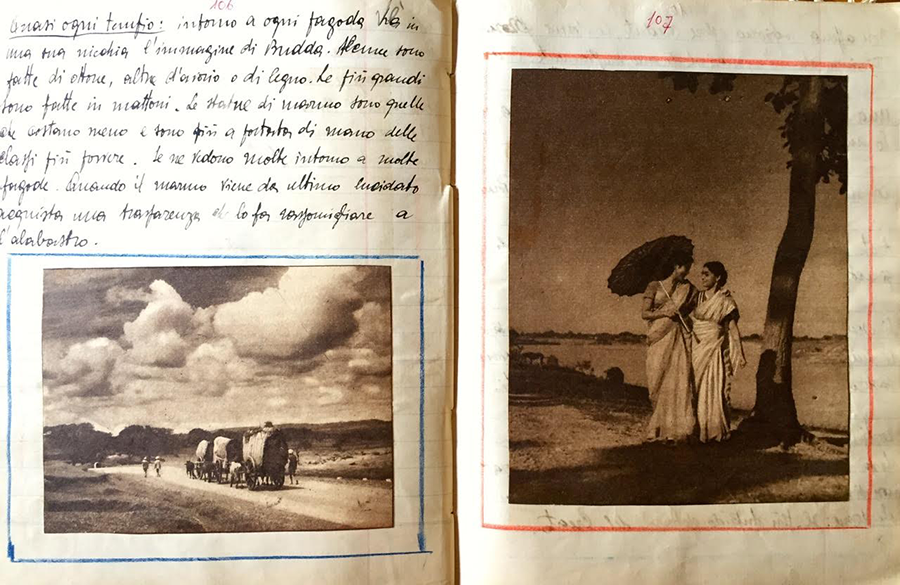

Just as my great-uncle Otto coped with his captivity by writing a novel, Raffaello Paganini, a Navy officer, survived by inking a series of portraits and paysages on toilet paper. Paganini, in a letter to his parents, wrote about “the many Indians, so many Indians who, when we walked out of the train, looked at us marching by, but did not laugh – instead they stared with serious and sad expressions on their faces. They seemed so beautiful to me, with their colourful clothes that looked like flowers”.

This is another charming aspect of the novel and of my great-uncle’s difficult, yet intense, experiences in India 70 years ago. As his fictional alter ego Diego prepares for his many escapes (getting regularly captured), we see an India of the Partition and of the Independence years, where most of the locals encountered do not treat the Italian prisoners on the run as hostile but as an exotic guest. Few are the episodes in which the runaways are denounced to the authorities. And this may be due to the fact that the escaping Italian officers in Latin Lovers strictly abide to the self-imposed rule of never stealing food, but always paying for provisions.

In Latin Lovers, after Diego has made a couple of failed efforts to escape from the Bangalore prison, news comes in of Japanese troops moving towards Singapore. This prompts the British command to send POW officers north to the Young Officers on Leave camp at the foot of the Himalayas. There’s plenty of literature on the Yol camp, 10 km west of Dharamsala. In the last decade, two other Italian novels have been published on the lives of the 12,000 Italian soldiers sent up there.

Yol was an impressive prison camp with hundreds of barracks on a 770-acre property. While the relationship with the locals was generally good, not all was rosy. Prisoners were granted freedom to explore the mountains and go on treks but to help map heights. As a result of this, one summitted mountain was named “Cima Italia” or Italian peak. In another instance, an Italian officer who repeatedly refused to stop singing a Fascist song in honour of the birth of Rome was shot dead and received, posthumously, the Medal of Honour. Killed for singing: so Italian.

There are still many stories in Yol of the lifestyles of Italian POWs. Some left behind their dogs with Italian names, Paletto (little stick), some cultivated vegetable gardens and distilled Grappa liquor, some would visit their Indian friends in the village, cook food and bring medicines.

This is also what was happening to the fictional Diego Taranto, who kept trying to escape nevertheless. In Latin Lovers, my great-uncle insisted that it was an officer’s duty to continue attempting escape: “it was the only way a prisoner could keep the enemy busy”. That might be, but Otto was also attracted by the magnetism of the mountains and of the ascent. He completed many climbs, meticulously documenting them in his drawing book, measuring altitudes, trying to let time pass, until he finally returned to his family and his country where he received the Cross of War medal. He died at 82, in my hometown.

Yol still stands. From August to October 1947, 12,000 Muslims were kept there on their way to Pakistan. From 1949 to 1952, it became a refugee camp for Kashmiri migrants. Then it was turned into military barracks, housing the Rising Star, the youngest battalion of the Indian Army.

It is still possible to visit it. Even to sleep in one of the barracks. People still report finding old rusted cans used by the Italians. They are a memento of a painful chapter in history. A chapter my great-uncle tried to express by writing a novel to cope with a trauma, and transform a memory into something useful for himself and for others.

Limited-time offer: Big stories, small price. Keep independent media alive. Become a Scroll member today!

Our journalism is for everyone. But you can get special privileges by buying an annual Scroll Membership. Sign up today!