Thirty-three year-old Lalbiaki is a counsellor with Mizoram’s AIDS Prevention and Control Society. Until last year, she would spend several days on the road every month, travelling the hills and valleys of Champhai in a white-coloured pickup with two colleagues – a lab technician and a driver – scouring the countryside for cases of AIDS.

Located along the Myanmar border, the district of Champhai is one of the principal routes through which drugs enter India. The district has high rates of drug addiction. Several of these addicts have HIV infections as well, the condition that almost inevitably leads to AIDS unless treated. The North East has among the highest prevalence rates of HIV in India, and within the region, Mizoram's figures are next only to neighbouring Manipur.

This places Lalbiaki's mobile unit at the vanguard of India's fight against AIDS. Tasked with spreading awareness about HIV in a high-risk region, and conducting blood tests that could help detect HIV positive cases early, it plays a crucial role in ensuring that the virus does not spill over into the rest of the population.

But for the last couple of months, the unit has been struggling to do its job. In addition to the salaries of the three staffers, its expenses come to Rs 11,000 a month. But between April 2014 and March this year, it received funds only three times.

As a result, the unit’s touring schedule is in a shambles. Every so often, when the team gets calls from villagers asking them to come for tests, Lalbiaki, a postgraduate in social work from Mizoram University, borrows money from friends and family to fund the travel.

Between January and March alone, she has borrowed Rs 13,600. Her monthly salary is Rs 13,000.

“We need to keep going to these villages,” she said. “If there is one positive [HIV Positive case] in the village and if there is no test, then he or she can spread the disease easily to others.”

In the late nineties, India put in place a set of elaborate protocols to prevent and contain the spread of AIDS. But delays in funding are now wrecking them. Lalbiaki and her colleagues betray a sense of urgent concern: without funds, they might not be able to stop the disease from exploding across the state, which could have serious repercussions not just for the region, but also for the rest of India.

Funding delays

To understand why funding delays are having such a deleterious impact on Mizoram's AIDS control programme, it's necessary to understand how India's AIDS control infrastructure works.

In the state, as in the rest of the country, every district has multiple “targeted intervention centres”. Run by local NGOs, these work with communities that are particularly susceptible to HIV, such as drug addicts and sex workers. To prevent the virus from spreading, the centres give free needles and condoms to their clients. They also take their clients for regular testing to gauge their HIV status.

For the rest of the population, the state AIDS control society operates mobile units of the sort Lalbiaki works with. It also runs Integrated Counselling and Testing Centres that test people's HIV status and provide medicines to control the condition. Champhai with its 83 villages has eight such standalone centres with their own lab technicians and counsellors. It also has another seven centres that are attached to primary health centres, where the AIDS control society provides test kits, but the work is done by the staff of the health department.

This infrastructure worked well until a year ago. Till 2010, said an official in the state AIDS control society, the number of new HIV cases was rising every month in the state. And then, in 2010-'11, it slowed to about 100-150 new cases a month. Even this slower rate has meant that from 4,000 cases across the state in 2010, Mizoram now has double the number of cases – according to the official, about 9,000-10,000 cases. With this funding delay, this number of new cases might rise faster once more.

To understand why, it helps to visit an NGOs like Agape, which works with the high-risk groups.

Prevention crumbled

Overlooking a busy traffic intersection that next to the biggest mall in Aizawl is a small building. Up the steps, so narrow that two people can pass each other with difficulty, and on the first floor, is a small room with four desks, a refrigerator, cardboard boxes on the floor and charts on the walls that are crammed with numbers.

This is a rehab centre for female intravenous drug users, run by Agape, a church-funded organisation that works with HIV-positive people and drug users through a rehab centre and two “targeted intervention” centres that are funded by Mizoram's AIDS control society.

Agape means “compassion” in Greek, but even this noble sentiment has not escaped the funding cuts.

The centre received funds in September and then again only in February, said Zothanpuii, the programme director. In October, the centre borrowed from the parent NGO and carried on as usual. In November, Agape's fieldworkers, who meet with the centre's drug user and sex worker clients, began cutting back on trips. These came down from five days a week to two days a week. In the next three months, trips to the field fell further – one day a week.

A chart on the wall facing Zothanpuii explains why. Monthly expenditure, which stood at Rs 3.5 lakh in September fell to Rs 1.3 lakh in October, Rs 25,837 in November. In December, it stood at an incredible Rs 1,569.

That was expenditure, said Zothanpuii, on just phone and internet bills.

At the Agape centre in Aizawl, plummeting numbers for expenses, and worried patients.

It's an easily understood chain of events. As Caravan reported in its April issue, since early 2014, the central government has stopped sending AIDS funds directly to the Mizoram's State Aids Control Society. Instead, it sends this money to the state finance department.

Mizoram has been going through a financial crisis for some years now. Its monthly expenditure exceeds its monthly inflows. The state treasury has been regularly redirecting funds for social sector programmes to salaries and other administrative expenses.

AIDS budgets, once routed to the treasury, met a similar fate. Said a senior official at the Mizoram AIDS control society, “We used to get direct funding from the centre. But, from last year, all CSS [centrally sponsored schemes] started going through the state treasury. That is when the delays started.”

In 2014, the National AIDS Control Organisation released April payments in June. It was August by the time the state released 40% of that amount.

Things worsened further when the National Democratic Alliance government slashed allocations to the National AIDS Control Organisation which funds the state AIDS control societies from Rs 1,785 cr to Rs 1,397 crore.

This was a staggering 21.7% drop. Speaking with Mint's Vidya Krishnan, union health minister JP Nadda justified the move. “AIDS was a concern ten years back,” he said.

In that sense, Mizoram’s AIDS programme has suffered a double whammy. It was affected by the nationwide crisis in India's AIDS programme, and when the depleted funds did reach Mizoram, they got stuck in the treasury.

The funding delays, said the official in the Mizoram AIDS society, have made its partner NGOs apprehensive. Uncertain of when the funds would come, “they did not want to take loans that they cannot repay”, he said. The only loans they took were small ones to pay salaries and attend to the most urgent work. And so, as the chart in Agape showed, outreach to the patients and the vulnerable communities suffered.

Missing syringes

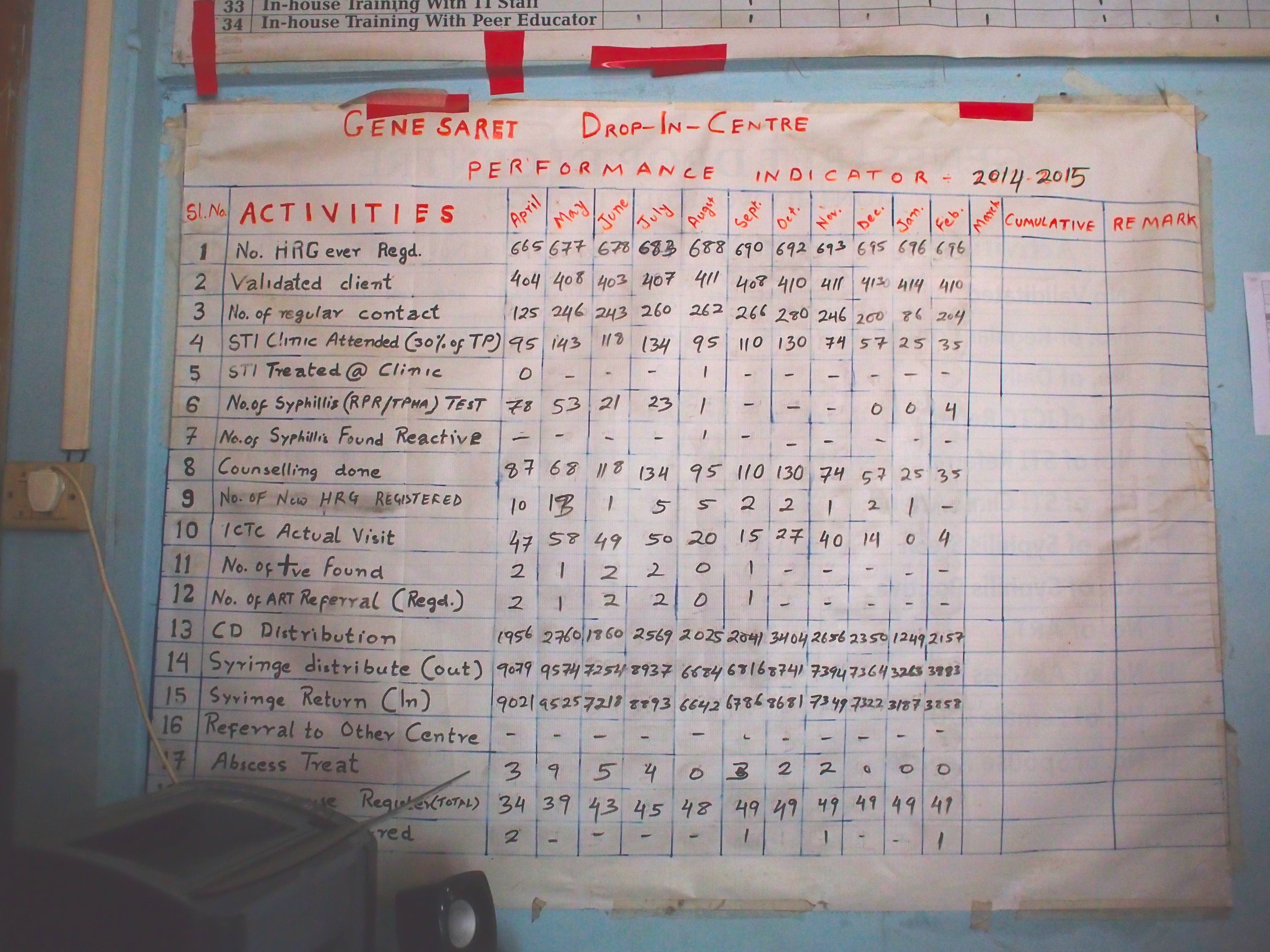

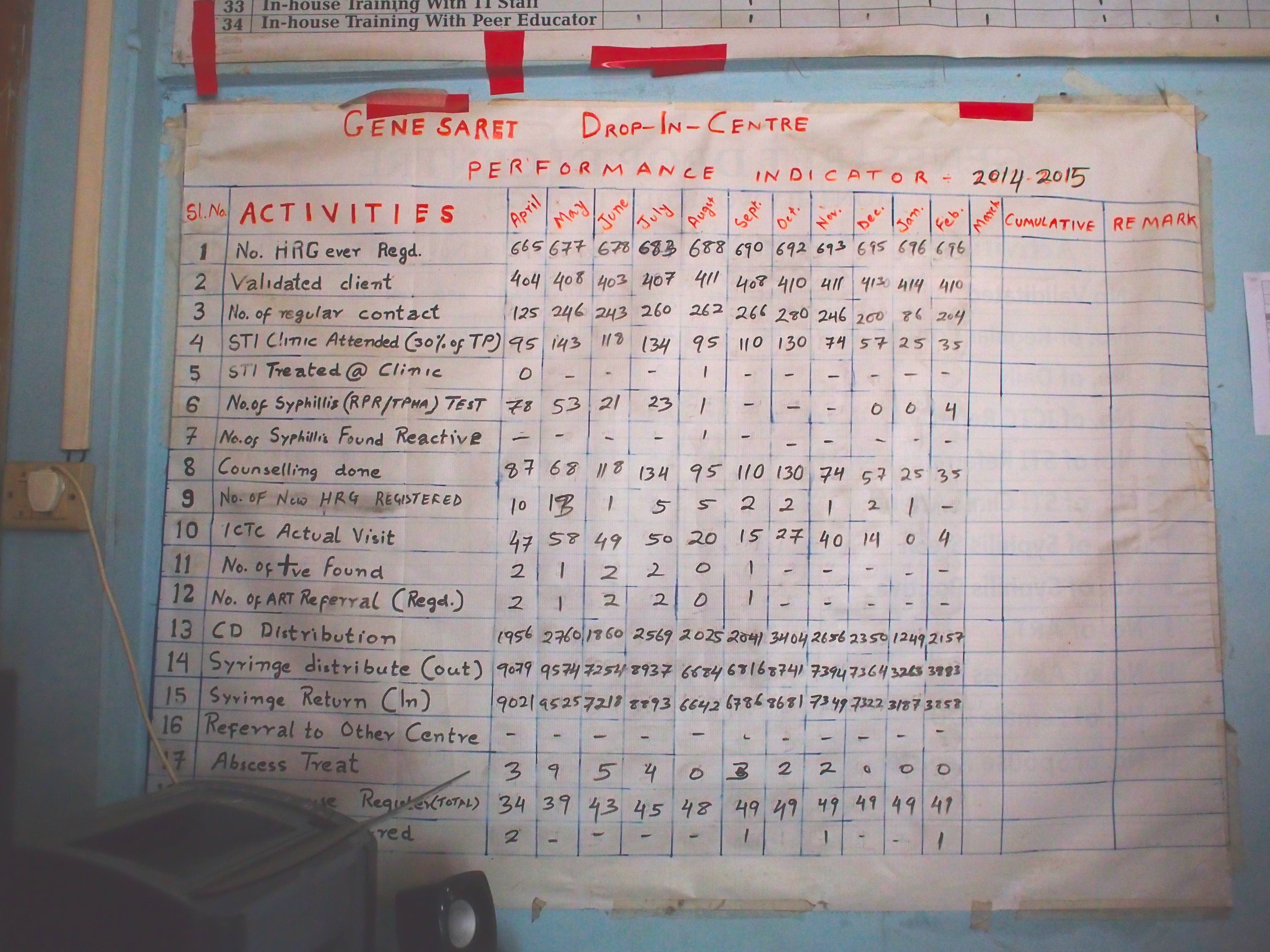

The pattern is repeated across centres. At the office of another “targeted intervention” centre, run by an NGO called Genesaret in Champhai, as Lalnunsanga, its accountant, was being interviewed, an addict came in. He was young, carried a backpack, was dressed in a t-shirt with an untucked, unbuttoned shirt over a pair of jeans that was rolled up over his muscular, veined calves. He wrote his name on a register next to the entrance, dropped in used needles, collected two new ones, fixed one to his syringe, and left.

Of Mizoram's HIV positive people, 27% are drug users. In Champhai, jewel of the drug trade, 60% of the HIV positive people are drug users.

But syringe distribution in Champhai is down from 9,079 last April to 3,883 in March.

Lalnunsanga, the accountant, said no money came between April and September. And then again none till February. The NGO, he said, took a loan to pay salaries but its work has suffered.

Even in the case of Agape, when its field trips went down, clients needed to either travel to its Dawrpui centre in Central Aizawl to get fresh needles or were forced to buy them in the market. Travelling costs money. So do the needles – between Rs 5-Rs 10. “Regular” addicts, said Zothanpuii, inject themselves as many as two-seven times a day. When needles are not available free, everyone doesn't buy new ones.

As Zothanpuii explained this, a young woman, not older than 30, sat nearby, overhearing this conversation. She had abscesses on both feet, a result of shooting heroin into her veins. As she waited for the doctor to clean and rebandage her feet, she confirmed what Zothanpuii had said. “When we do not get needles, we share with our friends,” she said.

In Champhai, many drug users are HIV positive. What makes matters worse is that most women coming to this centre are sex workers. Their clients are migrant workers and locals from rural areas. Through shared needles, and paid sex, HIV is very likely to be spreading to the rest of the population.

The collapse of monitoring

It would be hard to estimate the spread of AIDS in the last few months because the funding delays have also weakened the state's ability to gauge people's HIV status.

In the past, NGOs like Generaset tested clients' HIV status at least twice every year. Simultaneously, the mobile units covered the rest of the population, testing pregnant women and other vulnerable sections like children from broken homes.

Today, both strategies are faltering.

Short on money, the NGOs are focusing only on the most acute cases. In Champhai, a visit to the Integrated Counselling and Testing Centre at the civil hospital means hiring an auto, which costs money. So Generaset now takes only the most important cases to the centre for testing, said Lalramluaha, a peer educator at Generaset at the NGO. “The ones who have been sharing syringes or having sex without condoms,” he said.

The chart on their wall showed visits by drug users to Integrated Counselling and Testing Centres centres were down from 47 in April 2014 to foiur in March. When asked about the number of cases referred for testing by the NGOs, Zonunmawii, the programme manager at the District AIDS Prevention and Control Unit, said the numbers have been falling every year – from 2,507 in 2011-12 to 987 last year. The drop in the visits of drug users is puzzling at a time when, by all accounts, the drug trade has picked up again.

The dropping numbers on the charts of Genesaret.

Even the mobile unit is struggling to keep up its search for new cases. In 2013, Lalbiaki's team covered 50-60 villages. Last year, the number came down to ten. “Depending on how much we raise, we do the outreach,” the counsellor said. “At the most, we manage to get into the middle of the district.”

This means people in the rest of Champhai have to travel to Integrated Counselling and Testing Centres for testing. While pregnant women are willing to travel, Lalbiaki maintained that the drug users are less willing.

What was adding to the problems, said Zonunmawii, the programme manager at the District AIDS Prevention and Control Unit, was the shortage of testing kits. “In January and February, there were no test kits,” he said. The official at the state AIDS Society confirmed the shortage. “Our demand for test kits will be about 40,000-60,000 a year," she said. "While we have enough ARTs [Anti-Retroviral Therapy] medicines for the positive people, the test kits have been a problem."

This is a pan-India problem. As Caravan reported, the supply of diagnostic kits has been affected due to a dispute between Roche Diagnostics and the Indian government over unpaid bills and prices.

In fact, about 45 days ago, Mizoram “borrowed” 9,500 test kits from Tamil Nadu.

The outcome

This all adds up to an increasingly skewed field. Even as it gets easier for AIDS to spread, the state's ability to find HIV positive people is falling. Today, Mizoram has 9,000-10,000 HIV positive people.

The official at the state AIDS society official said it is hard to predict at the moment how these numbers will change. The head of the society, Dr Lalmalsawmi Sailo, did not respond to a request for a meeting.

But at the Agape centre, there are already signs that the disease is taking deeper root. Every month, some of its clients go to the AIDS society's centre for testing. Until last September, said Lalengmawii, a project manager at the centre, there were some months each year when no client would test positive. However, since then, every month has yielded at least one positive case, even though the number of people getting tested has fallen.

None of these processes are unique to Champhai and Aizawl. Said the official, “Champhai is particularly badly off as it is the worst drugs and AIDS affected district in the state. But this will be happening all over the state.”

A view of the rooftops in Champhai, on the border with Myanmar.

To get things back on track, the AIDS Society needs to start getting its funds on time. But that seems unlikely because the state’s finances have worsened since last year, and the centre has not yet informed Mizoram about its allocations for the current financial year. The AIDS Society does not know what how much money it will be allocated for its work this year.

“Last year was very bad,” said the official. “Hopefully, that will not happen this year. If we know how much we will get this year, we can plan.”

The situation has reached such a pass that the state health mission, which is similarly cash strapped, has lent Rs 50 lakh to the AIDS programme. Said a senior official in the health mission, “The ARTs [Anti-Retroviral Therapy medicines] are being maintained at the cost of salaries.”

As a backup, the AIDS society has started to turn to non-governmental bodies like the Church. But that comes with its own costs. Some churches are willing to fund all the activities need in the AIDS programme, as Agape illustrates. Others, however, are unwilling to fund needles or condom distribution, and prefer sticking to sponsoring awareness campaigns, working with pregnant women and helping the HIV-positive people.

Either way, the help is welcome. Individuals, institutions, everyone in Mizoram appears to be pitching in the best they can to contain AIDS. Everyone except the Indian state.

Located along the Myanmar border, the district of Champhai is one of the principal routes through which drugs enter India. The district has high rates of drug addiction. Several of these addicts have HIV infections as well, the condition that almost inevitably leads to AIDS unless treated. The North East has among the highest prevalence rates of HIV in India, and within the region, Mizoram's figures are next only to neighbouring Manipur.

This places Lalbiaki's mobile unit at the vanguard of India's fight against AIDS. Tasked with spreading awareness about HIV in a high-risk region, and conducting blood tests that could help detect HIV positive cases early, it plays a crucial role in ensuring that the virus does not spill over into the rest of the population.

But for the last couple of months, the unit has been struggling to do its job. In addition to the salaries of the three staffers, its expenses come to Rs 11,000 a month. But between April 2014 and March this year, it received funds only three times.

As a result, the unit’s touring schedule is in a shambles. Every so often, when the team gets calls from villagers asking them to come for tests, Lalbiaki, a postgraduate in social work from Mizoram University, borrows money from friends and family to fund the travel.

Between January and March alone, she has borrowed Rs 13,600. Her monthly salary is Rs 13,000.

“We need to keep going to these villages,” she said. “If there is one positive [HIV Positive case] in the village and if there is no test, then he or she can spread the disease easily to others.”

In the late nineties, India put in place a set of elaborate protocols to prevent and contain the spread of AIDS. But delays in funding are now wrecking them. Lalbiaki and her colleagues betray a sense of urgent concern: without funds, they might not be able to stop the disease from exploding across the state, which could have serious repercussions not just for the region, but also for the rest of India.

Funding delays

To understand why funding delays are having such a deleterious impact on Mizoram's AIDS control programme, it's necessary to understand how India's AIDS control infrastructure works.

In the state, as in the rest of the country, every district has multiple “targeted intervention centres”. Run by local NGOs, these work with communities that are particularly susceptible to HIV, such as drug addicts and sex workers. To prevent the virus from spreading, the centres give free needles and condoms to their clients. They also take their clients for regular testing to gauge their HIV status.

For the rest of the population, the state AIDS control society operates mobile units of the sort Lalbiaki works with. It also runs Integrated Counselling and Testing Centres that test people's HIV status and provide medicines to control the condition. Champhai with its 83 villages has eight such standalone centres with their own lab technicians and counsellors. It also has another seven centres that are attached to primary health centres, where the AIDS control society provides test kits, but the work is done by the staff of the health department.

This infrastructure worked well until a year ago. Till 2010, said an official in the state AIDS control society, the number of new HIV cases was rising every month in the state. And then, in 2010-'11, it slowed to about 100-150 new cases a month. Even this slower rate has meant that from 4,000 cases across the state in 2010, Mizoram now has double the number of cases – according to the official, about 9,000-10,000 cases. With this funding delay, this number of new cases might rise faster once more.

To understand why, it helps to visit an NGOs like Agape, which works with the high-risk groups.

Prevention crumbled

Overlooking a busy traffic intersection that next to the biggest mall in Aizawl is a small building. Up the steps, so narrow that two people can pass each other with difficulty, and on the first floor, is a small room with four desks, a refrigerator, cardboard boxes on the floor and charts on the walls that are crammed with numbers.

This is a rehab centre for female intravenous drug users, run by Agape, a church-funded organisation that works with HIV-positive people and drug users through a rehab centre and two “targeted intervention” centres that are funded by Mizoram's AIDS control society.

Agape means “compassion” in Greek, but even this noble sentiment has not escaped the funding cuts.

The centre received funds in September and then again only in February, said Zothanpuii, the programme director. In October, the centre borrowed from the parent NGO and carried on as usual. In November, Agape's fieldworkers, who meet with the centre's drug user and sex worker clients, began cutting back on trips. These came down from five days a week to two days a week. In the next three months, trips to the field fell further – one day a week.

A chart on the wall facing Zothanpuii explains why. Monthly expenditure, which stood at Rs 3.5 lakh in September fell to Rs 1.3 lakh in October, Rs 25,837 in November. In December, it stood at an incredible Rs 1,569.

That was expenditure, said Zothanpuii, on just phone and internet bills.

At the Agape centre in Aizawl, plummeting numbers for expenses, and worried patients.

It's an easily understood chain of events. As Caravan reported in its April issue, since early 2014, the central government has stopped sending AIDS funds directly to the Mizoram's State Aids Control Society. Instead, it sends this money to the state finance department.

Mizoram has been going through a financial crisis for some years now. Its monthly expenditure exceeds its monthly inflows. The state treasury has been regularly redirecting funds for social sector programmes to salaries and other administrative expenses.

AIDS budgets, once routed to the treasury, met a similar fate. Said a senior official at the Mizoram AIDS control society, “We used to get direct funding from the centre. But, from last year, all CSS [centrally sponsored schemes] started going through the state treasury. That is when the delays started.”

In 2014, the National AIDS Control Organisation released April payments in June. It was August by the time the state released 40% of that amount.

Things worsened further when the National Democratic Alliance government slashed allocations to the National AIDS Control Organisation which funds the state AIDS control societies from Rs 1,785 cr to Rs 1,397 crore.

This was a staggering 21.7% drop. Speaking with Mint's Vidya Krishnan, union health minister JP Nadda justified the move. “AIDS was a concern ten years back,” he said.

In that sense, Mizoram’s AIDS programme has suffered a double whammy. It was affected by the nationwide crisis in India's AIDS programme, and when the depleted funds did reach Mizoram, they got stuck in the treasury.

The funding delays, said the official in the Mizoram AIDS society, have made its partner NGOs apprehensive. Uncertain of when the funds would come, “they did not want to take loans that they cannot repay”, he said. The only loans they took were small ones to pay salaries and attend to the most urgent work. And so, as the chart in Agape showed, outreach to the patients and the vulnerable communities suffered.

Missing syringes

The pattern is repeated across centres. At the office of another “targeted intervention” centre, run by an NGO called Genesaret in Champhai, as Lalnunsanga, its accountant, was being interviewed, an addict came in. He was young, carried a backpack, was dressed in a t-shirt with an untucked, unbuttoned shirt over a pair of jeans that was rolled up over his muscular, veined calves. He wrote his name on a register next to the entrance, dropped in used needles, collected two new ones, fixed one to his syringe, and left.

Of Mizoram's HIV positive people, 27% are drug users. In Champhai, jewel of the drug trade, 60% of the HIV positive people are drug users.

But syringe distribution in Champhai is down from 9,079 last April to 3,883 in March.

Lalnunsanga, the accountant, said no money came between April and September. And then again none till February. The NGO, he said, took a loan to pay salaries but its work has suffered.

Even in the case of Agape, when its field trips went down, clients needed to either travel to its Dawrpui centre in Central Aizawl to get fresh needles or were forced to buy them in the market. Travelling costs money. So do the needles – between Rs 5-Rs 10. “Regular” addicts, said Zothanpuii, inject themselves as many as two-seven times a day. When needles are not available free, everyone doesn't buy new ones.

As Zothanpuii explained this, a young woman, not older than 30, sat nearby, overhearing this conversation. She had abscesses on both feet, a result of shooting heroin into her veins. As she waited for the doctor to clean and rebandage her feet, she confirmed what Zothanpuii had said. “When we do not get needles, we share with our friends,” she said.

In Champhai, many drug users are HIV positive. What makes matters worse is that most women coming to this centre are sex workers. Their clients are migrant workers and locals from rural areas. Through shared needles, and paid sex, HIV is very likely to be spreading to the rest of the population.

The collapse of monitoring

It would be hard to estimate the spread of AIDS in the last few months because the funding delays have also weakened the state's ability to gauge people's HIV status.

In the past, NGOs like Generaset tested clients' HIV status at least twice every year. Simultaneously, the mobile units covered the rest of the population, testing pregnant women and other vulnerable sections like children from broken homes.

Today, both strategies are faltering.

Short on money, the NGOs are focusing only on the most acute cases. In Champhai, a visit to the Integrated Counselling and Testing Centre at the civil hospital means hiring an auto, which costs money. So Generaset now takes only the most important cases to the centre for testing, said Lalramluaha, a peer educator at Generaset at the NGO. “The ones who have been sharing syringes or having sex without condoms,” he said.

The chart on their wall showed visits by drug users to Integrated Counselling and Testing Centres centres were down from 47 in April 2014 to foiur in March. When asked about the number of cases referred for testing by the NGOs, Zonunmawii, the programme manager at the District AIDS Prevention and Control Unit, said the numbers have been falling every year – from 2,507 in 2011-12 to 987 last year. The drop in the visits of drug users is puzzling at a time when, by all accounts, the drug trade has picked up again.

The dropping numbers on the charts of Genesaret.

Even the mobile unit is struggling to keep up its search for new cases. In 2013, Lalbiaki's team covered 50-60 villages. Last year, the number came down to ten. “Depending on how much we raise, we do the outreach,” the counsellor said. “At the most, we manage to get into the middle of the district.”

This means people in the rest of Champhai have to travel to Integrated Counselling and Testing Centres for testing. While pregnant women are willing to travel, Lalbiaki maintained that the drug users are less willing.

What was adding to the problems, said Zonunmawii, the programme manager at the District AIDS Prevention and Control Unit, was the shortage of testing kits. “In January and February, there were no test kits,” he said. The official at the state AIDS Society confirmed the shortage. “Our demand for test kits will be about 40,000-60,000 a year," she said. "While we have enough ARTs [Anti-Retroviral Therapy] medicines for the positive people, the test kits have been a problem."

This is a pan-India problem. As Caravan reported, the supply of diagnostic kits has been affected due to a dispute between Roche Diagnostics and the Indian government over unpaid bills and prices.

In fact, about 45 days ago, Mizoram “borrowed” 9,500 test kits from Tamil Nadu.

The outcome

This all adds up to an increasingly skewed field. Even as it gets easier for AIDS to spread, the state's ability to find HIV positive people is falling. Today, Mizoram has 9,000-10,000 HIV positive people.

The official at the state AIDS society official said it is hard to predict at the moment how these numbers will change. The head of the society, Dr Lalmalsawmi Sailo, did not respond to a request for a meeting.

But at the Agape centre, there are already signs that the disease is taking deeper root. Every month, some of its clients go to the AIDS society's centre for testing. Until last September, said Lalengmawii, a project manager at the centre, there were some months each year when no client would test positive. However, since then, every month has yielded at least one positive case, even though the number of people getting tested has fallen.

None of these processes are unique to Champhai and Aizawl. Said the official, “Champhai is particularly badly off as it is the worst drugs and AIDS affected district in the state. But this will be happening all over the state.”

A view of the rooftops in Champhai, on the border with Myanmar.

To get things back on track, the AIDS Society needs to start getting its funds on time. But that seems unlikely because the state’s finances have worsened since last year, and the centre has not yet informed Mizoram about its allocations for the current financial year. The AIDS Society does not know what how much money it will be allocated for its work this year.

“Last year was very bad,” said the official. “Hopefully, that will not happen this year. If we know how much we will get this year, we can plan.”

The situation has reached such a pass that the state health mission, which is similarly cash strapped, has lent Rs 50 lakh to the AIDS programme. Said a senior official in the health mission, “The ARTs [Anti-Retroviral Therapy medicines] are being maintained at the cost of salaries.”

As a backup, the AIDS society has started to turn to non-governmental bodies like the Church. But that comes with its own costs. Some churches are willing to fund all the activities need in the AIDS programme, as Agape illustrates. Others, however, are unwilling to fund needles or condom distribution, and prefer sticking to sponsoring awareness campaigns, working with pregnant women and helping the HIV-positive people.

Either way, the help is welcome. Individuals, institutions, everyone in Mizoram appears to be pitching in the best they can to contain AIDS. Everyone except the Indian state.

Scroll has produced award-winning journalism despite violent threats, falling ad revenues and rising costs. Support our work. Become a member today.

In these volatile times, Scroll remains steadfastly courageous, nuanced and comprehensive. Become a Scroll Member and support our award-winning reportage, commentary and culture writing.