There is a simple reason why most pro-net neutrality activists prefer to insist that the neutrality debate is black and white: give an inch and they will take a mile. This is an understandable position to take considering the players involved on the anti-neutrality side are international giants, like Google and Facebook; domestic giants, like Airtel and Reliance; and, at least going by the consultation paper, even the telecom regulator. In reality, however, there are lots of good arguments against neutrality, which itself is a term that has many different definitions.

First a reminder of the basic concept. Net neutrality is the idea that service providers treat all traffic on the internet the same. That means no preferential treatment for any sort of data. No fast lanes, no free lanes, no special prices for Skype or Viber. Net neutrality activists are specifically asking the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India to make sure that telecom companies are prohibited from offering some portions of the internet, whether it is WhatsApp or Wikipedia, at a different price to others.

Not everyone agrees, and it is not just because of greedy telecom companies. Here are a few reasons to be anti-neutrality, along with the pro-neutrality responses to them.

Individual Liberties 1: Freedom to innovate

Pro-neutrality activists are asking TRAI not to bring in any licensing of apps or websites on the internet, since current law already applies to the web, and a licensing regime would be an obstacle to innovation. At the same time, they are also asking the regulator to bring in rules to prohibit a company from trying out different business models online, such as creating a fast-lane for high-bandwidth services or offering a select number of services for free.

In both scenarios, it is valid to ask not "how" authorities should regulate but "whether" any regulation is necessary. Customers might not like the fact that they have to pay more for certain things and app-makers might not want to be left out of a free zone, but there is an argument to be made about leaving the marketplace free from fetters. Why should the government come in the way? As with apps, current competition laws also apply to internet service providers. Beyond this, shouldn't companies, especially ones that built the infrastructure which gives access to the internet, be free to innovate?

NN counter: Telecom companies already submit to regulation when they enter the business, so it isn't a perfectly free market to begin with. And that regulation aims to serve the purposes of India's telecom policy, i.e. not to ensure a free market for business, but to provide "secure, reliable and high-quality telecom services to all citizens".

One of the objectives of the National Telecom Policy laid out in 2012? "Mandate an ecosystem to ensure setting up of a common platform for interconnection of various networks for providing non-exclusive and non-discriminatory access." It's a reference to phone calls, but of course is easily extendable to all telecom services.

Individual Liberties 2: Regulatory capture

One reasonable argument is that government regulation will end up standing in the way of the National Telecom Policy's universal access objectives, rather than helping it along. State governments, to give an example, have in the past ended up blocking access to electricity transmission lines rather than facilitating it for their own interests, and "regulatory capture", where such regulations are used to benefit preferred incumbents is a familiar problem of fettered markets.

By requiring TRAI to clear any sort of fresh business model or differential pricing agreement, we are giving more discretion to the regulator instead of to customers. Without TRAI's interference, customers would be free to decide what services and pricing model works best for them.

NN counter: TRAI already plays that discretionary role and regulatory capture is more of a likelihood without a framework governing the internet, such as net neutrality, than with. If net neutrality is embraced as a principle that furthers the National Telecom Policy, then every decision of TRAI's, or even another court, would have to flow from that principle.

Spreading the wealth: Free internet

The anger at Airtel Zero and Internet.org has confused lots of people. Those are "zero-rated" programmes, which effectively involve letting services, like Facebook, subsidise internet usage so that the customer doesn't have to pay for data. Anyone using Airtel Zero or Internet.org can use things like Facebook without having to spend anything. Yet net neutrality proponents are dead set against this, because some services will be priced differently to others.

Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg and Airtel have hit back at what has been called "net neutrality absolutism". They argue that this isn't against neutrality, because there are no fast lanes, and also insist some free internet services are more likely to get more people online than no free internet. How could free data be bad? And if Facebook wants to pay for me to use its service, why shouldn't it?

NN counter: Zero rating is still an unsettled issue, with lots of neutrality proponents uncomfortable with rejecting services that seem to expand access to the internet. The arguments against it are more about byproducts than free internet per se.

Zero-rated services would balkanize the internet, creating separate free zones for each service provider. They would also naturally favour incumbent big businesses, since those would have the funds to subsidise free data, potentially stifling innovation. Since there aren't that many ISPs, they also open up the potential for effective extortion, since no service would want to be left out of a free zone. Essentially it creates a "poor internet".

All of that may be defensible as being price innovations, but they could also be anti-competitive and, more importantly, they do not serve the National Telecom Policy's aim of universal connectivity since it is not the "open internet" that users will have access to. Whether the regulator has a legal freedom to prevent this, however, is up for debate.

Fast lanes: More efficient internet

The original neutrality debate involves ISPs charging more for certain kinds of data. Skype calls and YouTube videos need to be uninterrupted and fast, while email access or Twitter can come in slower and still be relatively seamless. ISPs argued that being allowed to charge more for certain services, like Skype, to be on a fast lane, would reduce congestion on their networks and make the internet better for everyone. Without it, they have argued, we are condemned to slow internet for all.

Worse, this prevents telecom operators from making money off of those services that use the internet a lot. Service providers have claimed that without the freedom to do this, and with falling voice and SMS revenues, they won't have the funds to invest in building more infrastructure for the 'net.

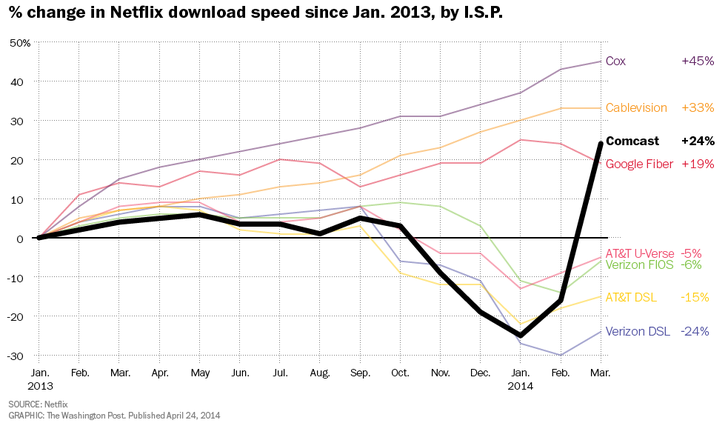

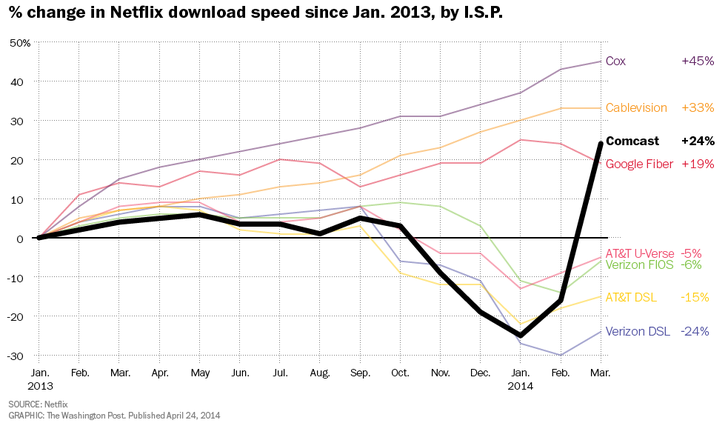

NN counter: See what happened to the speeds of video-streaming website Netflix when it was negotiating with American internet service provider Comcast last year over how much it would have to pay.

Neutrality activists believe that fast lanes will easily become a way for ISPs to extort money from services – who after all would want their service on the "slow lane". This could become similar to the way cable networks operate, a system that is control-accessed and therefore stifles innovation and new entrants.

First a reminder of the basic concept. Net neutrality is the idea that service providers treat all traffic on the internet the same. That means no preferential treatment for any sort of data. No fast lanes, no free lanes, no special prices for Skype or Viber. Net neutrality activists are specifically asking the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India to make sure that telecom companies are prohibited from offering some portions of the internet, whether it is WhatsApp or Wikipedia, at a different price to others.

Not everyone agrees, and it is not just because of greedy telecom companies. Here are a few reasons to be anti-neutrality, along with the pro-neutrality responses to them.

Individual Liberties 1: Freedom to innovate

Pro-neutrality activists are asking TRAI not to bring in any licensing of apps or websites on the internet, since current law already applies to the web, and a licensing regime would be an obstacle to innovation. At the same time, they are also asking the regulator to bring in rules to prohibit a company from trying out different business models online, such as creating a fast-lane for high-bandwidth services or offering a select number of services for free.

In both scenarios, it is valid to ask not "how" authorities should regulate but "whether" any regulation is necessary. Customers might not like the fact that they have to pay more for certain things and app-makers might not want to be left out of a free zone, but there is an argument to be made about leaving the marketplace free from fetters. Why should the government come in the way? As with apps, current competition laws also apply to internet service providers. Beyond this, shouldn't companies, especially ones that built the infrastructure which gives access to the internet, be free to innovate?

NN counter: Telecom companies already submit to regulation when they enter the business, so it isn't a perfectly free market to begin with. And that regulation aims to serve the purposes of India's telecom policy, i.e. not to ensure a free market for business, but to provide "secure, reliable and high-quality telecom services to all citizens".

One of the objectives of the National Telecom Policy laid out in 2012? "Mandate an ecosystem to ensure setting up of a common platform for interconnection of various networks for providing non-exclusive and non-discriminatory access." It's a reference to phone calls, but of course is easily extendable to all telecom services.

Individual Liberties 2: Regulatory capture

One reasonable argument is that government regulation will end up standing in the way of the National Telecom Policy's universal access objectives, rather than helping it along. State governments, to give an example, have in the past ended up blocking access to electricity transmission lines rather than facilitating it for their own interests, and "regulatory capture", where such regulations are used to benefit preferred incumbents is a familiar problem of fettered markets.

By requiring TRAI to clear any sort of fresh business model or differential pricing agreement, we are giving more discretion to the regulator instead of to customers. Without TRAI's interference, customers would be free to decide what services and pricing model works best for them.

NN counter: TRAI already plays that discretionary role and regulatory capture is more of a likelihood without a framework governing the internet, such as net neutrality, than with. If net neutrality is embraced as a principle that furthers the National Telecom Policy, then every decision of TRAI's, or even another court, would have to flow from that principle.

Spreading the wealth: Free internet

The anger at Airtel Zero and Internet.org has confused lots of people. Those are "zero-rated" programmes, which effectively involve letting services, like Facebook, subsidise internet usage so that the customer doesn't have to pay for data. Anyone using Airtel Zero or Internet.org can use things like Facebook without having to spend anything. Yet net neutrality proponents are dead set against this, because some services will be priced differently to others.

Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg and Airtel have hit back at what has been called "net neutrality absolutism". They argue that this isn't against neutrality, because there are no fast lanes, and also insist some free internet services are more likely to get more people online than no free internet. How could free data be bad? And if Facebook wants to pay for me to use its service, why shouldn't it?

NN counter: Zero rating is still an unsettled issue, with lots of neutrality proponents uncomfortable with rejecting services that seem to expand access to the internet. The arguments against it are more about byproducts than free internet per se.

Zero-rated services would balkanize the internet, creating separate free zones for each service provider. They would also naturally favour incumbent big businesses, since those would have the funds to subsidise free data, potentially stifling innovation. Since there aren't that many ISPs, they also open up the potential for effective extortion, since no service would want to be left out of a free zone. Essentially it creates a "poor internet".

All of that may be defensible as being price innovations, but they could also be anti-competitive and, more importantly, they do not serve the National Telecom Policy's aim of universal connectivity since it is not the "open internet" that users will have access to. Whether the regulator has a legal freedom to prevent this, however, is up for debate.

Fast lanes: More efficient internet

The original neutrality debate involves ISPs charging more for certain kinds of data. Skype calls and YouTube videos need to be uninterrupted and fast, while email access or Twitter can come in slower and still be relatively seamless. ISPs argued that being allowed to charge more for certain services, like Skype, to be on a fast lane, would reduce congestion on their networks and make the internet better for everyone. Without it, they have argued, we are condemned to slow internet for all.

Worse, this prevents telecom operators from making money off of those services that use the internet a lot. Service providers have claimed that without the freedom to do this, and with falling voice and SMS revenues, they won't have the funds to invest in building more infrastructure for the 'net.

NN counter: See what happened to the speeds of video-streaming website Netflix when it was negotiating with American internet service provider Comcast last year over how much it would have to pay.

Neutrality activists believe that fast lanes will easily become a way for ISPs to extort money from services – who after all would want their service on the "slow lane". This could become similar to the way cable networks operate, a system that is control-accessed and therefore stifles innovation and new entrants.

Scroll has produced award-winning journalism despite violent threats, falling ad revenues and rising costs. Support our work. Become a member today.

In these volatile times, Scroll remains steadfastly courageous, nuanced and comprehensive. Become a Scroll Member and support our award-winning reportage, commentary and culture writing.