Dalits might form around a quarter of India’s population, but they are almost entirely absent from history books. A new social media initiative is attempting to change that. Dalit History Month has been posting stories and placards daily on iconic Dalit figures through history since April 1 and will end on April 30. This also happens to be the birth month of Bhimrao Ambedkar.

The seven-member collective was formed in response to a Dalit padyatra in November 2014 that gained a lot of online and offline attention in India and abroad. The conversation began there. People began to speak of the need to write their own history but did not have the numbers to do it right away.

“Everyone in our community was talking about the need for [writing Dalit history],” said Vee Karunakaran, a member of the collective. “But this really started with the yatra. All of us who were scattered around with different strengths and backgrounds found each other and that is how we formed the collective.”

The 2011 census pegged the official number of Scheduled Castes in India at 200 million and Scheduled Tribes at 100 million.These numbers do not include the millions who have embraced Buddhism, Christianity, Sikhism or Islam. Yet in the never-ending battle for textbooks between left and right views of history, Dalit history gets entirely sidelined. What enters textbooks instead is a caste Hindu narrative weighted towards north India and Hindu epics, members of the collective say. They ecided to change that.

“One of the most discriminatory things is the treatment that Dr BR Ambedkar gets in our history books,” Karunakaran said. “They don’t have any choice but to mention him as the architect of the Constitution. The treatment he gets though is unfair. I take that very personally.”

Piecing fragments

Gathering information has been difficult.

“There is a body of information out there but it is difficult to access and it took us time to bring it all together,” said Christina Dhanaraj, another member. “Essentially, when we look at how history has been told, it comes from the perspective of a non-Dalit experience. We wanted to unlock our own histories and lay bare how untrue and incorrect its narration has been for a very long time.”

What is different now, she added, is that many Dalits have the intellectual capital to analyse, understand, and put together what had been happening to the community over the years.

While the group does end up relying on non-Dalit sources of written history, one significant hurdle has been to access the oral histories of the community. A lot of the work is about calling and emailing activists and putting people from various communities in touch with each other. There is, for instance, not much communication between Dalit Buddhist and Dalit Christian communities. So the members ask them about their personal histories and what is important to them.

“Some parts of our history exist in an unwritten form, in non-traditional media as well; such as folklore, songs and plays,” said Karunakaran. “We are trying to reduce scholarship from non-Dalit agencies or from agencies that actively put forth Dalit history without Dalit participation.”

A major inspiration for the group is Black History Month, observed in February, which celebrates the history and contribution of African-Americans to the US. Schools in the US devoted the month to exploring African-American themes. The Dalit group thinks that would be an ideal.

“We hope to bring that much legitimacy to our institutions,” Karunakaran said. “We do not want it taught as much alongside mainstream history, but as challenging that narrative.”

The need for Dalit history is reflected in the high traffic on the Facebook page: it had reached 80,000 people as of Thursday. To help it travel even further, volunteers have begun to translate the English posts into Hindi, Tamil, Punjabi, Marathi, Malayalam, Telugu and Gujarati. One volunteer has even offered to translate posts into French.

On April 5, the group held a Wikipedia Hackathon at the Michigan Institute of Technology that added Dalit histories to the community encyclopedia. A parallel timeline built with community contributions already has over 200 entries, running 2,000 years back to the Rig Veda.

Dealing with criticism

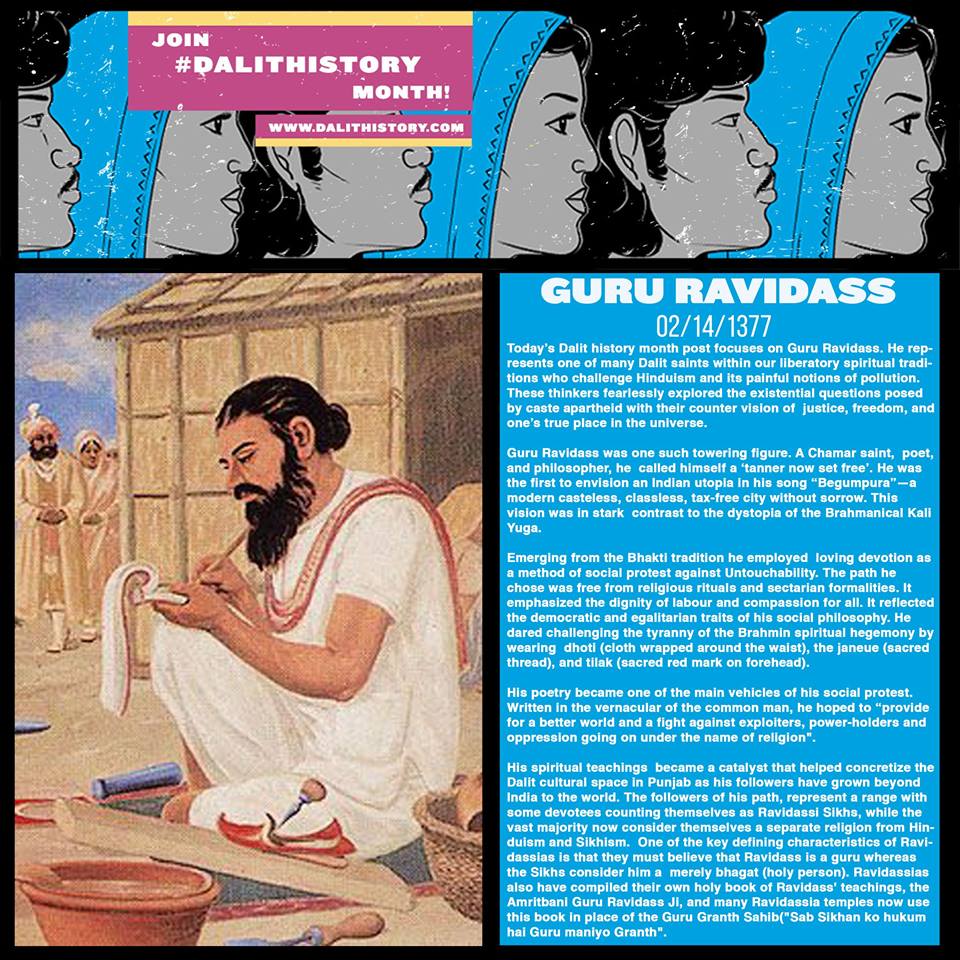

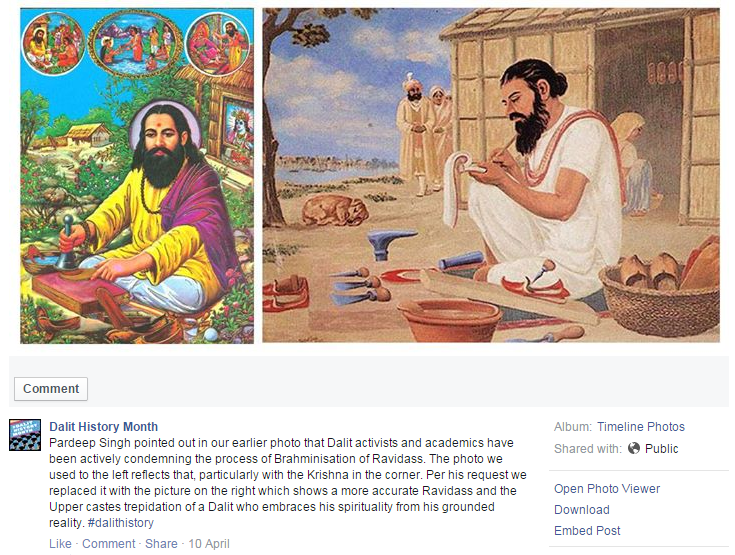

The collective has already demonstrated its openness to criticism from the community. An early post on Guru Ravidas showed a caste-Hindu depiction of him as a saint, complete with a Vishnu in the background. Following complaints, they replaced it with a more representative image and an apology.

Everyone does not get the same treatment. One user seems to have commented on their Facebook page saying that the movement was #breakingindia. That comment is no longer visible, though Dalit History Month’s categorical reply to it about the importance of Dalit history remains.

“We understand that there are some counter-narratives involved,” said Dhanaraj. “The first step is to get the world to recognise that we Dalits have a very rich history that is not just about atrocities but more so about resistance and resilience, and we are very proud of it.”

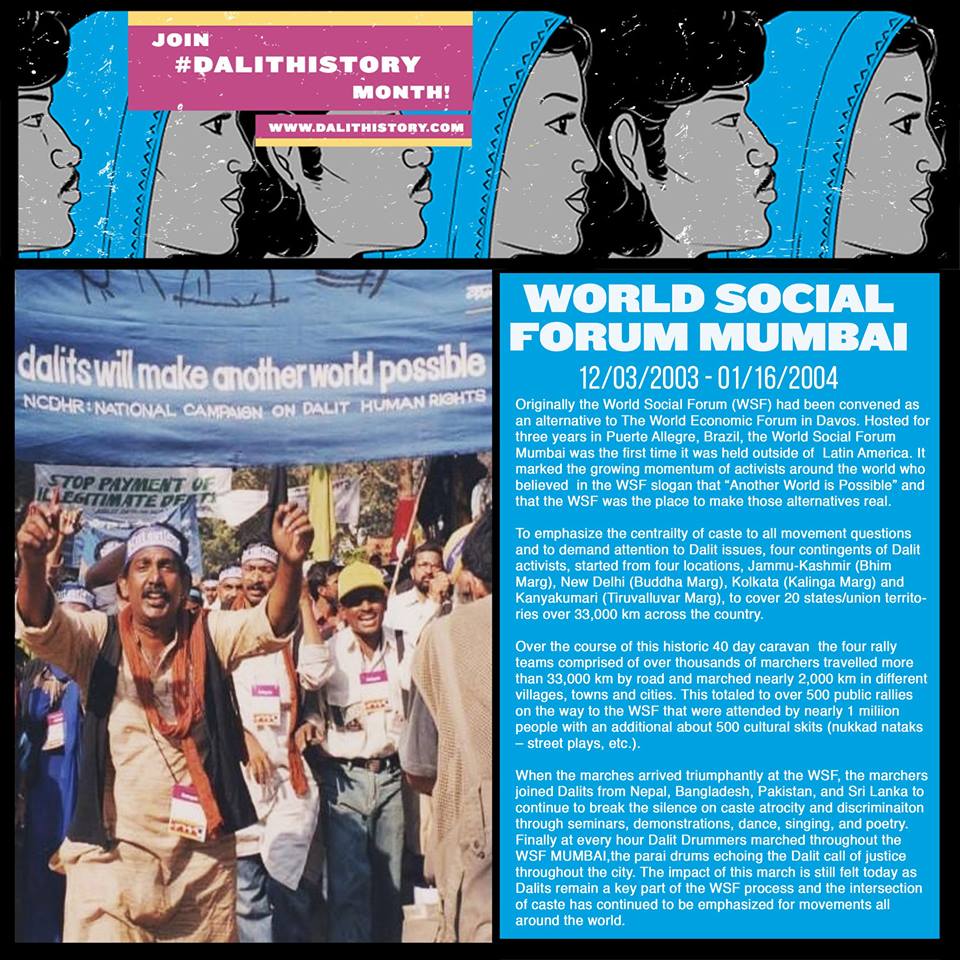

Here are some other posts from Dalit History Month:

The seven-member collective was formed in response to a Dalit padyatra in November 2014 that gained a lot of online and offline attention in India and abroad. The conversation began there. People began to speak of the need to write their own history but did not have the numbers to do it right away.

“Everyone in our community was talking about the need for [writing Dalit history],” said Vee Karunakaran, a member of the collective. “But this really started with the yatra. All of us who were scattered around with different strengths and backgrounds found each other and that is how we formed the collective.”

The 2011 census pegged the official number of Scheduled Castes in India at 200 million and Scheduled Tribes at 100 million.These numbers do not include the millions who have embraced Buddhism, Christianity, Sikhism or Islam. Yet in the never-ending battle for textbooks between left and right views of history, Dalit history gets entirely sidelined. What enters textbooks instead is a caste Hindu narrative weighted towards north India and Hindu epics, members of the collective say. They ecided to change that.

“One of the most discriminatory things is the treatment that Dr BR Ambedkar gets in our history books,” Karunakaran said. “They don’t have any choice but to mention him as the architect of the Constitution. The treatment he gets though is unfair. I take that very personally.”

Piecing fragments

Gathering information has been difficult.

“There is a body of information out there but it is difficult to access and it took us time to bring it all together,” said Christina Dhanaraj, another member. “Essentially, when we look at how history has been told, it comes from the perspective of a non-Dalit experience. We wanted to unlock our own histories and lay bare how untrue and incorrect its narration has been for a very long time.”

What is different now, she added, is that many Dalits have the intellectual capital to analyse, understand, and put together what had been happening to the community over the years.

While the group does end up relying on non-Dalit sources of written history, one significant hurdle has been to access the oral histories of the community. A lot of the work is about calling and emailing activists and putting people from various communities in touch with each other. There is, for instance, not much communication between Dalit Buddhist and Dalit Christian communities. So the members ask them about their personal histories and what is important to them.

“Some parts of our history exist in an unwritten form, in non-traditional media as well; such as folklore, songs and plays,” said Karunakaran. “We are trying to reduce scholarship from non-Dalit agencies or from agencies that actively put forth Dalit history without Dalit participation.”

A major inspiration for the group is Black History Month, observed in February, which celebrates the history and contribution of African-Americans to the US. Schools in the US devoted the month to exploring African-American themes. The Dalit group thinks that would be an ideal.

“We hope to bring that much legitimacy to our institutions,” Karunakaran said. “We do not want it taught as much alongside mainstream history, but as challenging that narrative.”

The need for Dalit history is reflected in the high traffic on the Facebook page: it had reached 80,000 people as of Thursday. To help it travel even further, volunteers have begun to translate the English posts into Hindi, Tamil, Punjabi, Marathi, Malayalam, Telugu and Gujarati. One volunteer has even offered to translate posts into French.

On April 5, the group held a Wikipedia Hackathon at the Michigan Institute of Technology that added Dalit histories to the community encyclopedia. A parallel timeline built with community contributions already has over 200 entries, running 2,000 years back to the Rig Veda.

Dealing with criticism

The collective has already demonstrated its openness to criticism from the community. An early post on Guru Ravidas showed a caste-Hindu depiction of him as a saint, complete with a Vishnu in the background. Following complaints, they replaced it with a more representative image and an apology.

Everyone does not get the same treatment. One user seems to have commented on their Facebook page saying that the movement was #breakingindia. That comment is no longer visible, though Dalit History Month’s categorical reply to it about the importance of Dalit history remains.

“We understand that there are some counter-narratives involved,” said Dhanaraj. “The first step is to get the world to recognise that we Dalits have a very rich history that is not just about atrocities but more so about resistance and resilience, and we are very proud of it.”

Here are some other posts from Dalit History Month:

Buy an annual Scroll Membership to support independent journalism and get special benefits.

Our journalism is for everyone. But you can get special privileges by buying an annual Scroll Membership. Sign up today!