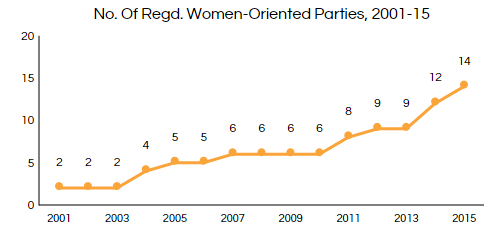

Since 2001, at least 14 political parties with a women-oriented political agenda have emerged across India, according to an analysis of an official list of political parties from April 2001 to January 2015.

Five of these parties have contested either a general election or a state assembly election in the past 15 years, according to statistical reports of elections to the Lok Sabha and state assemblies.

Despite a low success rate (with 100% deposit forfeited in all cases), most of these parties have survived, and the trend of registration of women’s issues-based parties has increased over the years, in a country where women comprise no more than 11.4% of the parliament.

As the graph above reveals, the number of such parties has increased from two in 2001 to 14 in 2015. Lucknow, the capital of Uttar Pradesh – a state with low levels of female development indices and empowerment – is seemingly a hub of such parties. India’s most-populous state accounts for nine parties with a women-oriented agenda.

With scant media coverage of these parties, it is difficult to ascertain what view of women’s rights they take. However, based on the names that they have been registered with, these parties seemingly represent different ideas. While some of them favour women empowerment, self-respect for women and women’s rights, there are also those which believe in a more universalist approach of constituting a women’s democratic front or organisation. A majority of them though have the chief agenda of organising women under one front.

All India Mahila Dal, which was registered on January 4, 1998, falls out of the purview of this study since it remained discontinued by 2001. However, a look at the agenda of this party and that of United Women Front reveals that both had similar aims of becoming national-level women’s parties yet were ready to accommodate men to achieve their ultimate objective of better representation for women’s interests.

Looking at the immediate aims of both the parties as reported, a broad observation can be made that descriptive representation remains their chief agenda whereby “political institutions should reflect the composition of civil society”.

In all, these parties are distributed across six states: West Bengal, Delhi, Uttar Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka and Maharashtra. These parties were registered in Delhi, Kolkata, Hyderabad, Bangalore, Mumbai and Lucknow, among capital cities, and Unnao, Chittor and Dharwad, among other cities.

Jagdeep S. Chhokar from Association of Democratic Reforms (ADR) suggests that since registered parties enjoy 100% tax exemption under section 13 A of the Income Tax Act, many are registered for tax-avoidance purposes, which might explain why between 75% and 80% of registered parties do not contest elections.

“Tax exemption is a primary draw to register a political party,” said Chhokar.

Of those who contest, success is a distant country

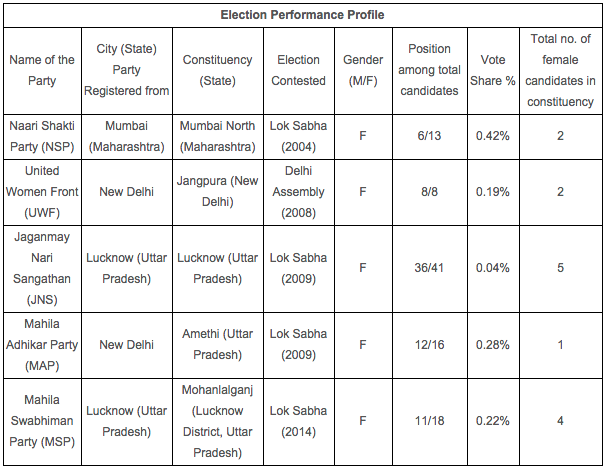

Of the women-oriented parties that have contested elections, one has contested the general elections in 2004, three in 2009 and one in 2014. One party also contested the 2008 Delhi state assembly elections.

A few key observations from the table above:

—None of the parties have been able to cross the 1% threshold of vote share. All deposits have been forfeited.

—All the parties except one have finished below the 50 percentile among all the contesting parties.

—The mean average percentage of female candidates contesting from all the constituencies is 12.5% and median average is 9.8%. All the candidates featured in the table above were women and thus contributed in increasing an otherwise quite low average of female candidates from these constituencies.

—All the parties have fielded solitary candidates in all the constituencies. While all other parties have contested elections from the city where the parties are originally based, Mahila Adhikar Party, based in New Delhi, fielded its candidate from an off-base constituency, UP’s Amethi, an Indian National Congress stronghold.

The United Women Front (UWF), which planned to field candidates for all 72 seats in the Delhi Assembly elections 2008, eventually fielded only one. Except UWF, none of these parties contested any election again. Since Mahila Swabhiman Party (MSP) was formed in 2014 and contested the Lok Sabha election the same year, its continued participation will be clear only in the next election.

One women-oriented party’s lonely struggle

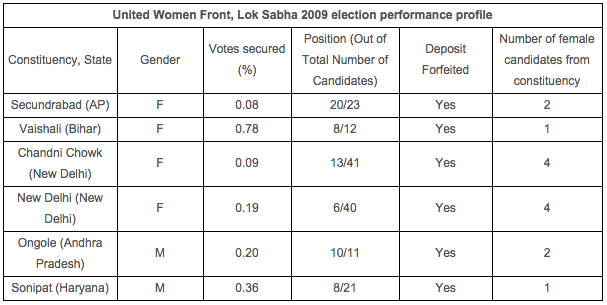

Since UWF fielded six candidates in the 2009 general elections, it provides fodder for more expansive analysis.

In a sense, the party, launched in 2007 in a blaze of publicity (as covered in The Hindu,WeNews.org and The Christian Science Monitor), follows India’s dynastic political proclivities. Its first president was Suman Krishan Kant, the wife of the former vice president, Krishan Kant.

The party’s agenda: remedy the lack of representation of women in parliament.

“We are tired of waiting for the Women’s Reservation Bill,” said Suman Kant. This lack of representation, according to Suman Kant, has been one of the reasons for the problems women face in society.

“Women have simply not been getting the kind of governance they deserve,” she said. “All this is precisely because we do not have enough women in decision-making and in political processes. A few women here and there cannot make much of a difference.”

The table below analyses the party’s performance in the 2009 elections.

The 2009 elections was the second such effort by the UWF and it led to a much-improved performance.

From a single candidate in the Delhi assembly elections in 2008, the party fielded six candidates from five cities in five states, aiming for a national presence. That year, it supposedly had local organisations in 16 states, led by veteran activists.

For instance, Shanti Das, a union activist, headed the Orissa chapter in 2008. She later became the national president of the party in 2011, taking over from Kant, who retired due to health issues.

The party’s participation in these elections was also special because it had fielded two male candidates, beside four female candidates.

“We are not against men,” Kant had said. “We need men to work with us and we need their support.” However, it was predetermined that men will not be part of the national committee and will only be members of state chapters, while only a woman can head the party.”

Despite the party’s electoral failure, it appears evident that voters did not consider UWF an unviable party: Finishing in the top 50 percentile of the total number of parties was a considerable success for a fledgling party.

Delhi and Andhra Pradesh fielded two candidates each, the other two candidates came from Bihar and Haryana respectively, where they did garner higher vote shares (0.78% and 0.36%) than in the first two states. In Vaishali (Bihar) and Sonipat (Haryana), the party candidates were the only women contesting.

The party did not contest either the next Lok Sabha elections or the Delhi state assembly elections. However in an interview with Gulf News in 2010, Kant reflected on the loss in the 2009 elections. “It was our first election and we haven’t lost hope. It will take time to come to power but we are happy that at least people are beginning to recognise the Front,” she said.

“We have formed branches all over the country including Delhi, Haryana, Orissa, Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, Punjab and the eastern states,” Kant added.

For women, every bit of electoral progress counts

For women, India is an electorally dismal landscape.

Of 543 Lok Sabha seats, only 668 female candidates were fielded, which is 8.1% of all candidates.

No more than 62 female candidates won, which means 9.3% of the women who contested were successful: 525 female candidates forfeited their deposits.

The percentage of women in Parliament, as we said earlier, is now 11.4%, much below the international average of 22% and puts India at a lowly 111th rank among 145 nations of the world, as per statistics provided by the Inter-Parliamentary Union and UN Women.

The outlook for women is uniformly bleak across India’s political landscape. The Bhartiya Janata Party, which won 282 of 543 Lok Sabha seats, fielded only 38 women out of 428candidates, or 8.9%.

The Indian National Congress had 60 women of 464 candidates, or 12.9%.

The candidates for the left parties, Communist Party of India and Communist Party of India (Marxist), were 8.9% and 11.8% female, respectively.

Women made up no more than 5.4% and 11.1% of candidates at the other two national parties, the Bahujan Samaj Party and Nationalist Congress Party, respectively.

National parties accounted for only 21.9% of total women contesting the polls. Ironically, a majority of these parties supported the Women’s Reservation Bill 2009 in Rajya Sabha, which guarantees a reservation of 33% seats in legislative bodies for women.

As Zoya Hasan, retired professor at Centre for Political Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, suggested in the introduction to her edited volume, Party and Party Politics in India, political parties may have “played a critical role in the democratic process, especially in drawing historically-disadvantaged sections of society into the political system.”

Yet what Amrita Basu, the Dominic J. Paino 1955 Professor of Political Science and Sexuality, Women’s and Gender Studies at Amherst College, observed in her report Women, Political Parties and Social Movements in South Asia in 2005 still holds true.

“There isn’t much to report on parties’ success in organising women,” wrote Basu, “Most political parties are male dominated and neglect women and women’s interests. Whereas women have played very visible and important roles at the higher echelons of power as heads of state, and at the grassroots level in social movements, they have been under-represented in political parties.”

Yet, the fact that 93.6% of female candidates were unable to save their deposit from being forfeited in the 2014 general elections suggests that neither political parties nor the electorate are prepared to seriously consider women as their representatives.

Yet, the rise, however small, of women-oriented parties is encouraging.

Equal representation, however, is no guarantee for better representation of female agendas in mainstream politics. As Basu observed, citing Shirin M. Rai, Professor of Politics and International Studies at University of Warwick, “Those women who have played leading roles in political parties have rarely addressed women’s interests and questions of gender inequality.”

This article was originally published on IndiaSpend.com, a data-driven and public-interest journalism non-profit.

Five of these parties have contested either a general election or a state assembly election in the past 15 years, according to statistical reports of elections to the Lok Sabha and state assemblies.

Despite a low success rate (with 100% deposit forfeited in all cases), most of these parties have survived, and the trend of registration of women’s issues-based parties has increased over the years, in a country where women comprise no more than 11.4% of the parliament.

Source: Election Commission of India

As the graph above reveals, the number of such parties has increased from two in 2001 to 14 in 2015. Lucknow, the capital of Uttar Pradesh – a state with low levels of female development indices and empowerment – is seemingly a hub of such parties. India’s most-populous state accounts for nine parties with a women-oriented agenda.

With scant media coverage of these parties, it is difficult to ascertain what view of women’s rights they take. However, based on the names that they have been registered with, these parties seemingly represent different ideas. While some of them favour women empowerment, self-respect for women and women’s rights, there are also those which believe in a more universalist approach of constituting a women’s democratic front or organisation. A majority of them though have the chief agenda of organising women under one front.

All India Mahila Dal, which was registered on January 4, 1998, falls out of the purview of this study since it remained discontinued by 2001. However, a look at the agenda of this party and that of United Women Front reveals that both had similar aims of becoming national-level women’s parties yet were ready to accommodate men to achieve their ultimate objective of better representation for women’s interests.

Looking at the immediate aims of both the parties as reported, a broad observation can be made that descriptive representation remains their chief agenda whereby “political institutions should reflect the composition of civil society”.

In all, these parties are distributed across six states: West Bengal, Delhi, Uttar Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka and Maharashtra. These parties were registered in Delhi, Kolkata, Hyderabad, Bangalore, Mumbai and Lucknow, among capital cities, and Unnao, Chittor and Dharwad, among other cities.

Jagdeep S. Chhokar from Association of Democratic Reforms (ADR) suggests that since registered parties enjoy 100% tax exemption under section 13 A of the Income Tax Act, many are registered for tax-avoidance purposes, which might explain why between 75% and 80% of registered parties do not contest elections.

“Tax exemption is a primary draw to register a political party,” said Chhokar.

Of those who contest, success is a distant country

Of the women-oriented parties that have contested elections, one has contested the general elections in 2004, three in 2009 and one in 2014. One party also contested the 2008 Delhi state assembly elections.

Source: Election Commission of India

A few key observations from the table above:

—None of the parties have been able to cross the 1% threshold of vote share. All deposits have been forfeited.

—All the parties except one have finished below the 50 percentile among all the contesting parties.

—The mean average percentage of female candidates contesting from all the constituencies is 12.5% and median average is 9.8%. All the candidates featured in the table above were women and thus contributed in increasing an otherwise quite low average of female candidates from these constituencies.

—All the parties have fielded solitary candidates in all the constituencies. While all other parties have contested elections from the city where the parties are originally based, Mahila Adhikar Party, based in New Delhi, fielded its candidate from an off-base constituency, UP’s Amethi, an Indian National Congress stronghold.

The United Women Front (UWF), which planned to field candidates for all 72 seats in the Delhi Assembly elections 2008, eventually fielded only one. Except UWF, none of these parties contested any election again. Since Mahila Swabhiman Party (MSP) was formed in 2014 and contested the Lok Sabha election the same year, its continued participation will be clear only in the next election.

One women-oriented party’s lonely struggle

Since UWF fielded six candidates in the 2009 general elections, it provides fodder for more expansive analysis.

In a sense, the party, launched in 2007 in a blaze of publicity (as covered in The Hindu,WeNews.org and The Christian Science Monitor), follows India’s dynastic political proclivities. Its first president was Suman Krishan Kant, the wife of the former vice president, Krishan Kant.

The party’s agenda: remedy the lack of representation of women in parliament.

“We are tired of waiting for the Women’s Reservation Bill,” said Suman Kant. This lack of representation, according to Suman Kant, has been one of the reasons for the problems women face in society.

“Women have simply not been getting the kind of governance they deserve,” she said. “All this is precisely because we do not have enough women in decision-making and in political processes. A few women here and there cannot make much of a difference.”

The table below analyses the party’s performance in the 2009 elections.

Source: Statistical Report Lok Sabha Election 2009

The 2009 elections was the second such effort by the UWF and it led to a much-improved performance.

From a single candidate in the Delhi assembly elections in 2008, the party fielded six candidates from five cities in five states, aiming for a national presence. That year, it supposedly had local organisations in 16 states, led by veteran activists.

For instance, Shanti Das, a union activist, headed the Orissa chapter in 2008. She later became the national president of the party in 2011, taking over from Kant, who retired due to health issues.

The party’s participation in these elections was also special because it had fielded two male candidates, beside four female candidates.

“We are not against men,” Kant had said. “We need men to work with us and we need their support.” However, it was predetermined that men will not be part of the national committee and will only be members of state chapters, while only a woman can head the party.”

Despite the party’s electoral failure, it appears evident that voters did not consider UWF an unviable party: Finishing in the top 50 percentile of the total number of parties was a considerable success for a fledgling party.

Delhi and Andhra Pradesh fielded two candidates each, the other two candidates came from Bihar and Haryana respectively, where they did garner higher vote shares (0.78% and 0.36%) than in the first two states. In Vaishali (Bihar) and Sonipat (Haryana), the party candidates were the only women contesting.

The party did not contest either the next Lok Sabha elections or the Delhi state assembly elections. However in an interview with Gulf News in 2010, Kant reflected on the loss in the 2009 elections. “It was our first election and we haven’t lost hope. It will take time to come to power but we are happy that at least people are beginning to recognise the Front,” she said.

“We have formed branches all over the country including Delhi, Haryana, Orissa, Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, Punjab and the eastern states,” Kant added.

For women, every bit of electoral progress counts

For women, India is an electorally dismal landscape.

Of 543 Lok Sabha seats, only 668 female candidates were fielded, which is 8.1% of all candidates.

No more than 62 female candidates won, which means 9.3% of the women who contested were successful: 525 female candidates forfeited their deposits.

The percentage of women in Parliament, as we said earlier, is now 11.4%, much below the international average of 22% and puts India at a lowly 111th rank among 145 nations of the world, as per statistics provided by the Inter-Parliamentary Union and UN Women.

The outlook for women is uniformly bleak across India’s political landscape. The Bhartiya Janata Party, which won 282 of 543 Lok Sabha seats, fielded only 38 women out of 428candidates, or 8.9%.

The Indian National Congress had 60 women of 464 candidates, or 12.9%.

The candidates for the left parties, Communist Party of India and Communist Party of India (Marxist), were 8.9% and 11.8% female, respectively.

Women made up no more than 5.4% and 11.1% of candidates at the other two national parties, the Bahujan Samaj Party and Nationalist Congress Party, respectively.

National parties accounted for only 21.9% of total women contesting the polls. Ironically, a majority of these parties supported the Women’s Reservation Bill 2009 in Rajya Sabha, which guarantees a reservation of 33% seats in legislative bodies for women.

As Zoya Hasan, retired professor at Centre for Political Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, suggested in the introduction to her edited volume, Party and Party Politics in India, political parties may have “played a critical role in the democratic process, especially in drawing historically-disadvantaged sections of society into the political system.”

Yet what Amrita Basu, the Dominic J. Paino 1955 Professor of Political Science and Sexuality, Women’s and Gender Studies at Amherst College, observed in her report Women, Political Parties and Social Movements in South Asia in 2005 still holds true.

“There isn’t much to report on parties’ success in organising women,” wrote Basu, “Most political parties are male dominated and neglect women and women’s interests. Whereas women have played very visible and important roles at the higher echelons of power as heads of state, and at the grassroots level in social movements, they have been under-represented in political parties.”

Yet, the fact that 93.6% of female candidates were unable to save their deposit from being forfeited in the 2014 general elections suggests that neither political parties nor the electorate are prepared to seriously consider women as their representatives.

Yet, the rise, however small, of women-oriented parties is encouraging.

Equal representation, however, is no guarantee for better representation of female agendas in mainstream politics. As Basu observed, citing Shirin M. Rai, Professor of Politics and International Studies at University of Warwick, “Those women who have played leading roles in political parties have rarely addressed women’s interests and questions of gender inequality.”

This article was originally published on IndiaSpend.com, a data-driven and public-interest journalism non-profit.

Limited-time offer: Big stories, small price. Keep independent media alive. Become a Scroll member today!

Our journalism is for everyone. But you can get special privileges by buying an annual Scroll Membership. Sign up today!