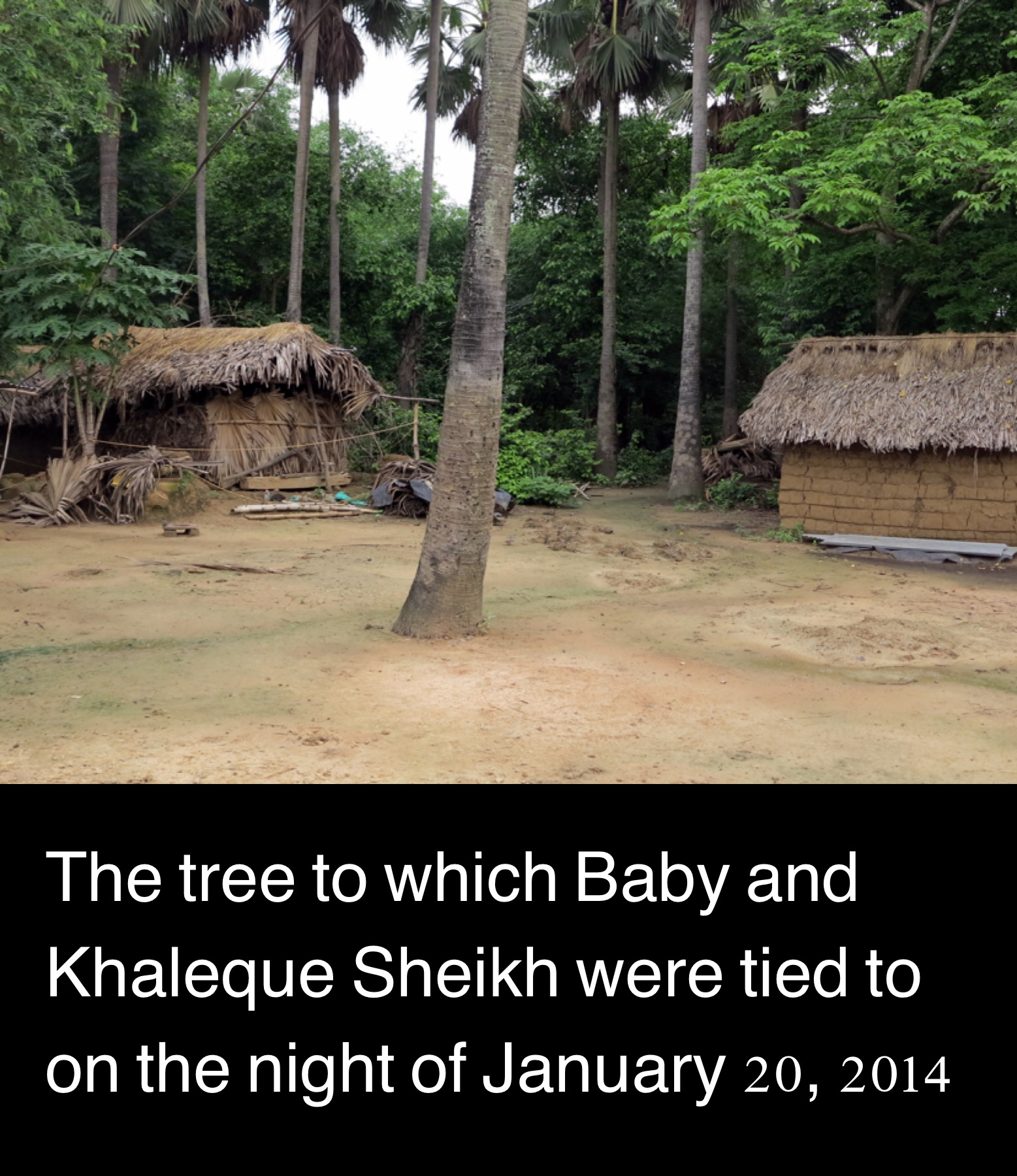

On January 22, 2014, a twenty-year-old woman approached the police in the rural hamlet of Subalpur in West Bengal, home to a community of Santhals, to say that she had been gang-raped by 13 men, under the order of the village council as punishment for her relationship with a non-tribal man. Sonia Faleiro investigated the case, conducting extensive interviews and field visits, to arrive at two versions of what had happened that night. The stories she unearthed have been published in the book 13 Men, the fifth title from Deca Books. Excerpts from an interview with Faleiro on the making of the book:

What made you pick this specific story?

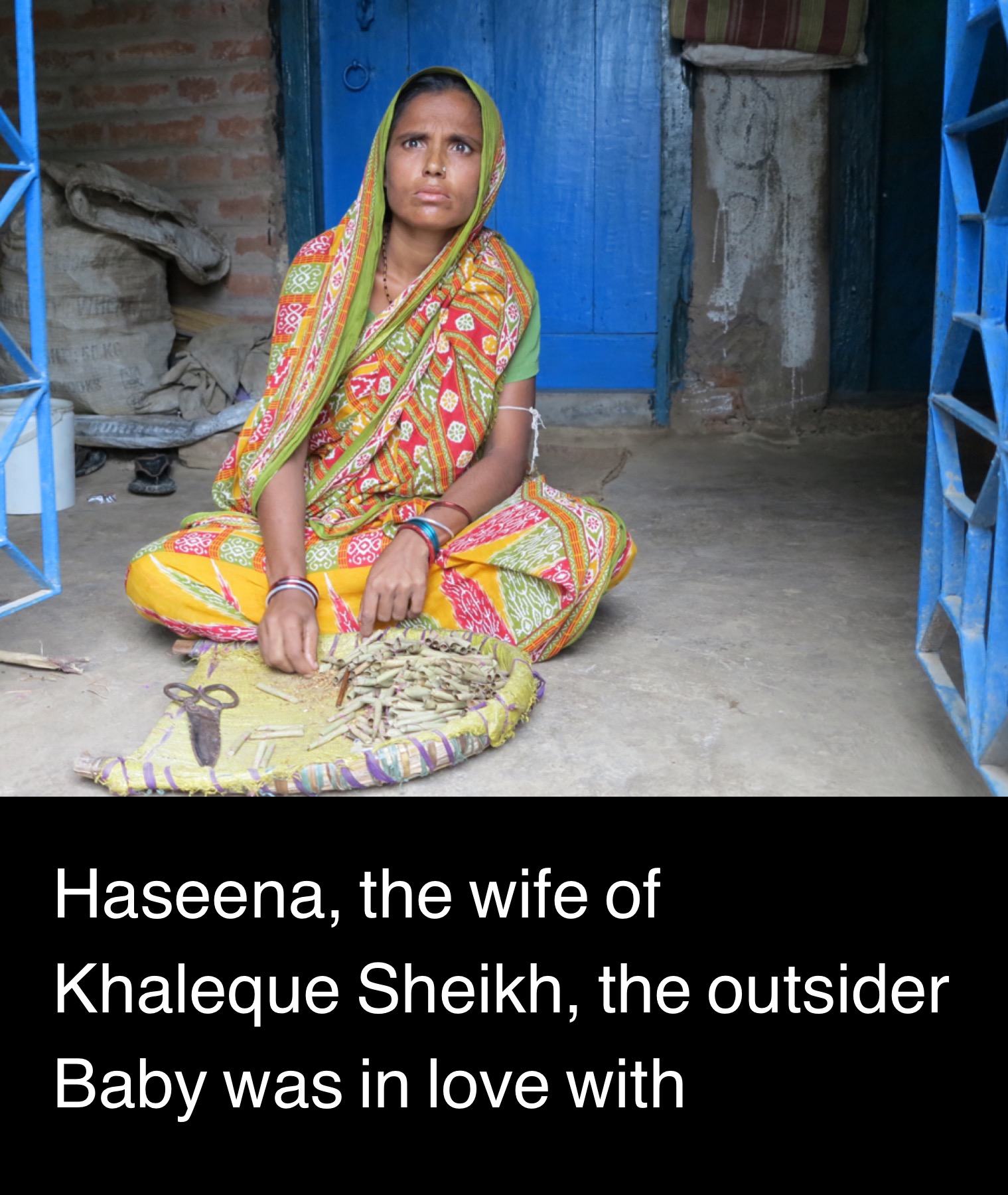

There were reports that the gang rape had been ordered by a village council – allegedly as punishment for the twenty-year-old woman’s relationship with a non-tribal man. The suggestion that rape in some places in India had official sanction made me want to learn more. The crime, not unlike what happened after the December 2012 Delhi bus gang rape, made headlines around the world. But the headlines, as I soon learnt, were inaccurate.

How long did it take you to report this story? How many people did you meet? How did you get them to part with the kind of personal information that appears in your book?

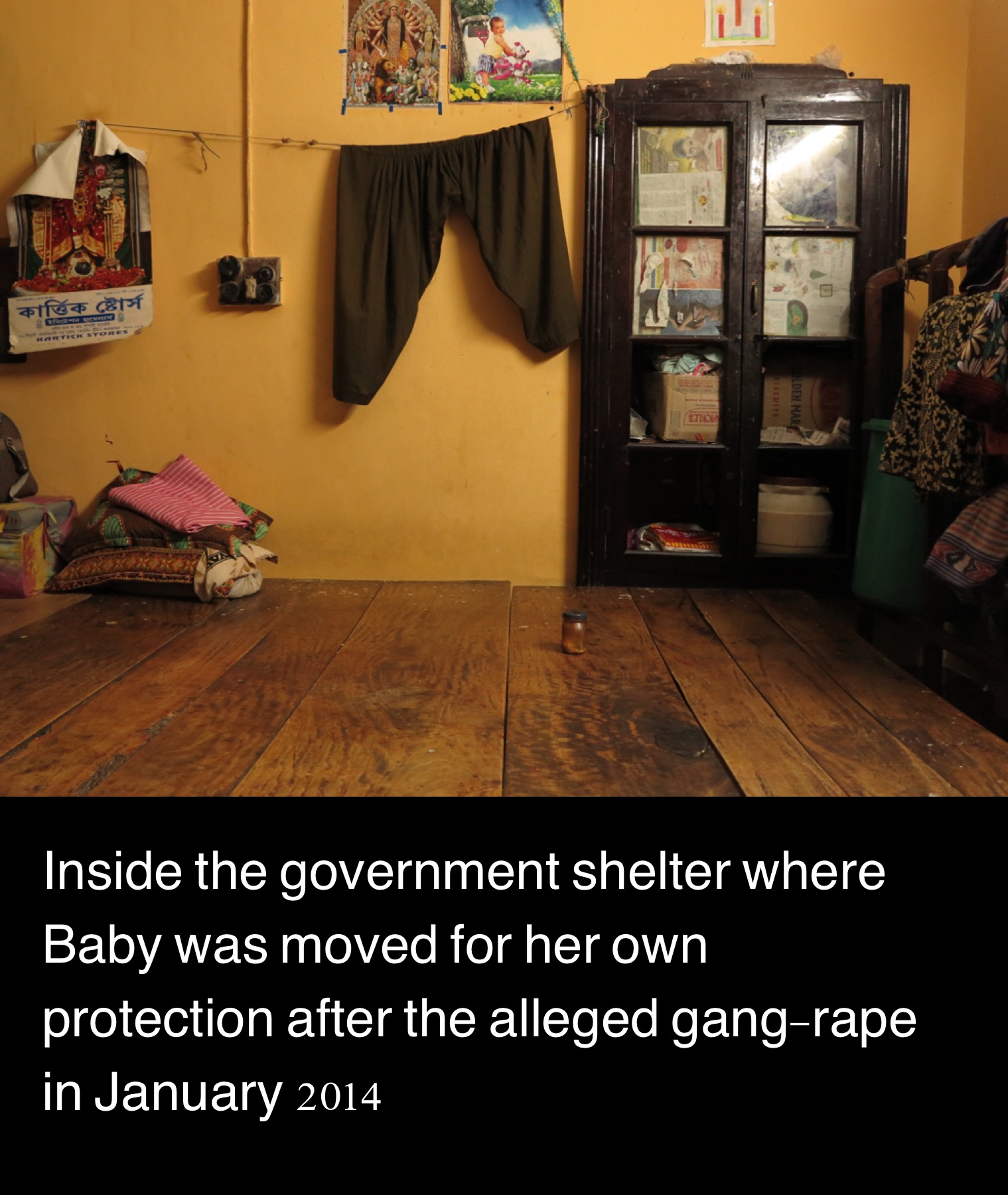

I took eight months to report the story. I met the families of the thirteen men. I met the investigating officers on the case, the politicians accused of concocting the rape complaint as a ploy to rob the Santhals of their mineral-rich land, and of course, inside a high security government home, I was given permission to conduct an exclusive interview with the young woman at the centre of it all – Baby (name changed). I continued my research long after I left Birbhum.

I don’t think there’s a trick to getting people to talk to you. They must want to. It helps if you intend to tell their story fairly. I work hard to be fair. I don’t pick sides when I report, and I hope that 13 Men reflects that.

You have left the key question - was the rape real or was it concocted? - open-ended, succeeding remarkably in maintaining an objective stance. Are you personally in doubt over it, or did you feel you didn’t have enough evidence to back your own surmise?

The court has declared its judgment, but lawyers for the men have filed an appeal. The truth is that nowhere in the world, let alone in India, where we have honed the act of victim-blaming to a fine art, is it advantageous for a woman to claim to have been raped. On the other hand, there is no scientific evidence to show that this rape happened. This vacuum draws necessary attention to the shortcomings of our justice system.

I do have an opinion on the events of the night, but to share it would be to pick a side and I won’t do that.

Your book sticks to the facts as you gleaned them. What are you personal observations about the social structure, power equations, gender relationships that you witnessed? Is anything changing? What are the larger issues you see behind this particular set of incidents?

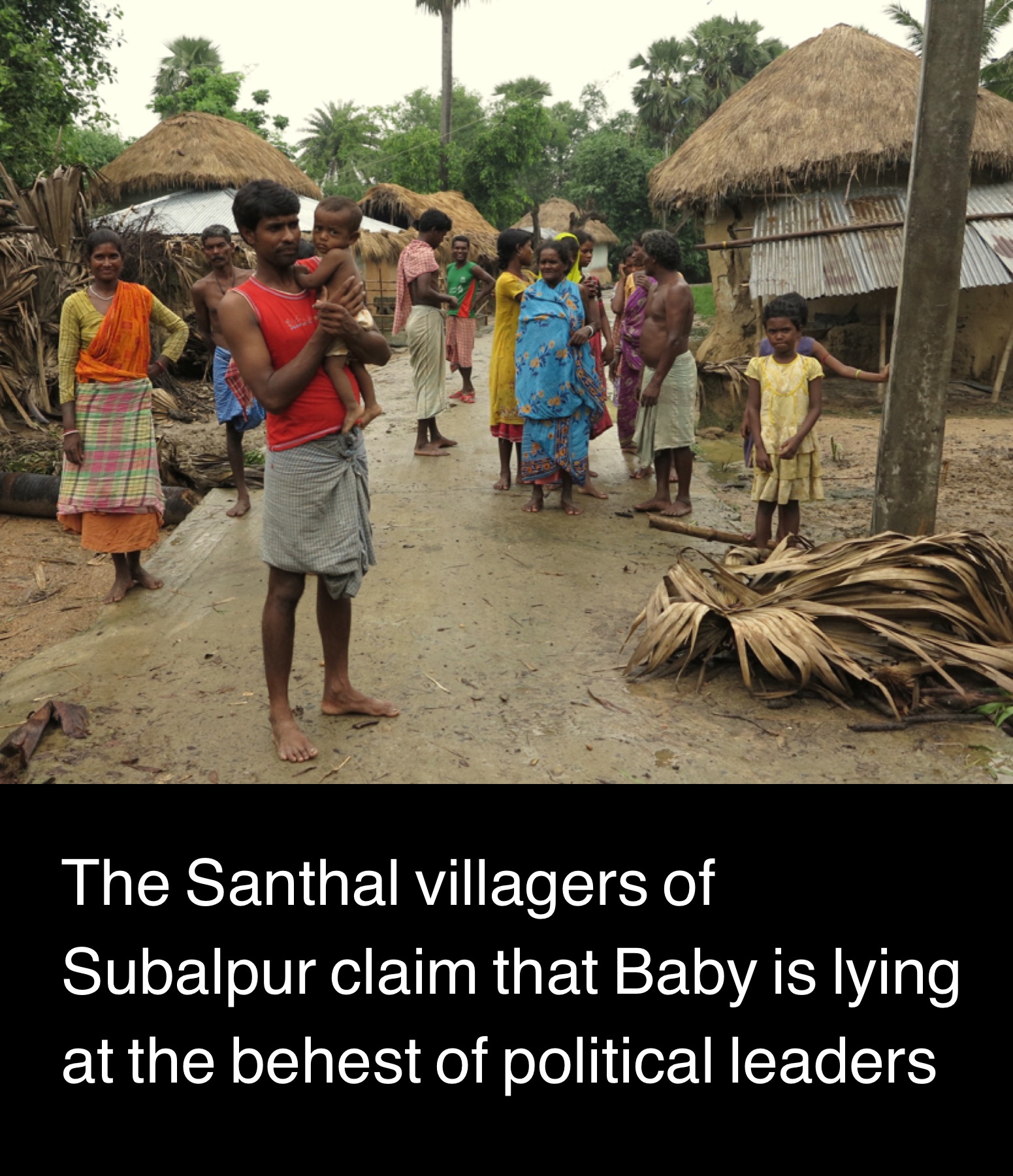

The Santhal villagers I interviewed are desperately poor and the verdict has devastated them. They can’t afford good legal representation, and they aren’t in a position to offer assistance to the families of the thirteen men – who are now without loved ones and breadwinners – because their own economic condition is so precarious. I feel great sympathy for them and I believe that the Indian government must take some responsibility for the deprivations that the Santhals in Subalpur, and elsewhere, continue to suffer. Tribal land must be protected from unscrupulous developers; their livelihood must be secured.

That said, the villagers’ behaviour towards Baby prior to the village council raises questions. Violence against women is a nationwide problem, so it hardly seems fair to single out the Santhals, but it is inaccurate for some to argue that Santhals have never participated in mob violence against women.

Vulnerable communities deserve empathy, protection, and support, but we must also accept that no one is immune from making bad choices and no one is above the law.

One of the things that come through in your book is that judgments in rape cases seem to have been fast-tracked, and that there was a serious attempt at rehabilitation and support for the survivor. Do you see this as a real attempt at change? Are you aware of whether it is being followed all over?

Baby’s case is a fascinating study because it shows exactly what has changed for the better since the December 2012 bus gang rape, but also where the system needs to be finessed. For example, the investigating officer on the case was the highly placed deputy superintendant of police, and he was given enough resources to lead an eight-member team. The trial was concluded within months. Baby received financial aid, land, and a house, and her mother, who was widowed when Baby was a child, received a small sum of money. On the other hand the trial was concluded before DNA and forensic reports were submitted.

Baby’s case isn’t the norm. She was at the centre of a tremendous media storm – reported everywhere from The New York Times to the BBC – and that put pressure on politicians to ensure that her case was fast-tracked.

Unfortunately, we are still a society that often times will only respond to complaints of violence against women if we feel the world is watching.

Do you think the new stringency in the rape laws will open up possibilities of personal and/or political vendetta as may have been the case here?

There will always be people who want to game the system for their own benefit. It’s up to the police to investigate all cases fully and fairly. But while applying the appropriate scrutiny to complaints, we must be sure not to harass and stigmatise survivors of rape.

Coincidentally – or not – the subject of rape is back on the national radar after the controversy over the India’s Daughter documentary. Do you have a position on the documentary and on the problems that several activists in India have associated with it?

The film has proved to be a Rorschach test. We see in it what we want to and that says more about us than it does about the film. As a reporter I found India’s Daughter to be an accurate, moving portrayal of a crime that deserves to be documented, on a subject about which we can simply never say enough.

All photographs: Sonia Faleiro

Sonia Faleiro is the author, most recently, of 13 Men and the cofounder of Deca, a global co-operative of long form journalists.

What made you pick this specific story?

There were reports that the gang rape had been ordered by a village council – allegedly as punishment for the twenty-year-old woman’s relationship with a non-tribal man. The suggestion that rape in some places in India had official sanction made me want to learn more. The crime, not unlike what happened after the December 2012 Delhi bus gang rape, made headlines around the world. But the headlines, as I soon learnt, were inaccurate.

How long did it take you to report this story? How many people did you meet? How did you get them to part with the kind of personal information that appears in your book?

I took eight months to report the story. I met the families of the thirteen men. I met the investigating officers on the case, the politicians accused of concocting the rape complaint as a ploy to rob the Santhals of their mineral-rich land, and of course, inside a high security government home, I was given permission to conduct an exclusive interview with the young woman at the centre of it all – Baby (name changed). I continued my research long after I left Birbhum.

I don’t think there’s a trick to getting people to talk to you. They must want to. It helps if you intend to tell their story fairly. I work hard to be fair. I don’t pick sides when I report, and I hope that 13 Men reflects that.

You have left the key question - was the rape real or was it concocted? - open-ended, succeeding remarkably in maintaining an objective stance. Are you personally in doubt over it, or did you feel you didn’t have enough evidence to back your own surmise?

The court has declared its judgment, but lawyers for the men have filed an appeal. The truth is that nowhere in the world, let alone in India, where we have honed the act of victim-blaming to a fine art, is it advantageous for a woman to claim to have been raped. On the other hand, there is no scientific evidence to show that this rape happened. This vacuum draws necessary attention to the shortcomings of our justice system.

I do have an opinion on the events of the night, but to share it would be to pick a side and I won’t do that.

Your book sticks to the facts as you gleaned them. What are you personal observations about the social structure, power equations, gender relationships that you witnessed? Is anything changing? What are the larger issues you see behind this particular set of incidents?

The Santhal villagers I interviewed are desperately poor and the verdict has devastated them. They can’t afford good legal representation, and they aren’t in a position to offer assistance to the families of the thirteen men – who are now without loved ones and breadwinners – because their own economic condition is so precarious. I feel great sympathy for them and I believe that the Indian government must take some responsibility for the deprivations that the Santhals in Subalpur, and elsewhere, continue to suffer. Tribal land must be protected from unscrupulous developers; their livelihood must be secured.

That said, the villagers’ behaviour towards Baby prior to the village council raises questions. Violence against women is a nationwide problem, so it hardly seems fair to single out the Santhals, but it is inaccurate for some to argue that Santhals have never participated in mob violence against women.

Vulnerable communities deserve empathy, protection, and support, but we must also accept that no one is immune from making bad choices and no one is above the law.

One of the things that come through in your book is that judgments in rape cases seem to have been fast-tracked, and that there was a serious attempt at rehabilitation and support for the survivor. Do you see this as a real attempt at change? Are you aware of whether it is being followed all over?

Baby’s case is a fascinating study because it shows exactly what has changed for the better since the December 2012 bus gang rape, but also where the system needs to be finessed. For example, the investigating officer on the case was the highly placed deputy superintendant of police, and he was given enough resources to lead an eight-member team. The trial was concluded within months. Baby received financial aid, land, and a house, and her mother, who was widowed when Baby was a child, received a small sum of money. On the other hand the trial was concluded before DNA and forensic reports were submitted.

Baby’s case isn’t the norm. She was at the centre of a tremendous media storm – reported everywhere from The New York Times to the BBC – and that put pressure on politicians to ensure that her case was fast-tracked.

Unfortunately, we are still a society that often times will only respond to complaints of violence against women if we feel the world is watching.

Do you think the new stringency in the rape laws will open up possibilities of personal and/or political vendetta as may have been the case here?

There will always be people who want to game the system for their own benefit. It’s up to the police to investigate all cases fully and fairly. But while applying the appropriate scrutiny to complaints, we must be sure not to harass and stigmatise survivors of rape.

Coincidentally – or not – the subject of rape is back on the national radar after the controversy over the India’s Daughter documentary. Do you have a position on the documentary and on the problems that several activists in India have associated with it?

The film has proved to be a Rorschach test. We see in it what we want to and that says more about us than it does about the film. As a reporter I found India’s Daughter to be an accurate, moving portrayal of a crime that deserves to be documented, on a subject about which we can simply never say enough.

All photographs: Sonia Faleiro

Sonia Faleiro is the author, most recently, of 13 Men and the cofounder of Deca, a global co-operative of long form journalists.

Just 0.2% of readers pay for news. The others don’t care if it dies. You can help make a difference. Support independent journalism – join Scroll now.

Our coverage is independent because of readers like you. Pay to be a Scroll member and help us keep going.