In the month since the the Charlie Hebdo tragedy, the significance of visual representation has been a topic of much discussion. Political cartoons have the potential to reinforce problematic stereotypes – and also to challenge them.

Relying on basic materials such as pencil and paper, cartoon and comics artists can readily respond to political and social issues; at their most impressive they draw out worlds that tend to remain unobserved.

At the same time, our easy access to visual images can, at times, encourage a superficial consideration of their impact. While there is an ongoing tradition of photographic works serving to inform their viewers, the repetition of particular images can also stereotype its subjects in problematic ways.

In other words, seeing, by itself, is not enough. How and what we see is also at stake. I’d like to draw attention to two comics that encourage readers to engage with stories of difference: Epileptic (2005) by David B. and The Arrival (2006) by Shaun Tan.

Epileptic

Originally published in six volumes as L’Ascension du Haut-Mal (1996-2003), Epileptic is the English translation of David B.’s memoir of his experiences growing up with an older brother, Jean-Christophe, who suffers from epilepsy.

Rendered in black and white, B.’s lyrical, confronting, and meticulous drawings access the anger and grief that Jean-Christophe’s condition provokes for the narrator, his family, and for Jean-Christophe himself. B. does not excuse any of the characters, including himself, from scrutiny, and indeed this intimate portrait of a family life is what makes the book so compelling. The book also reflects on the privileges and pitfalls that accompany vision.

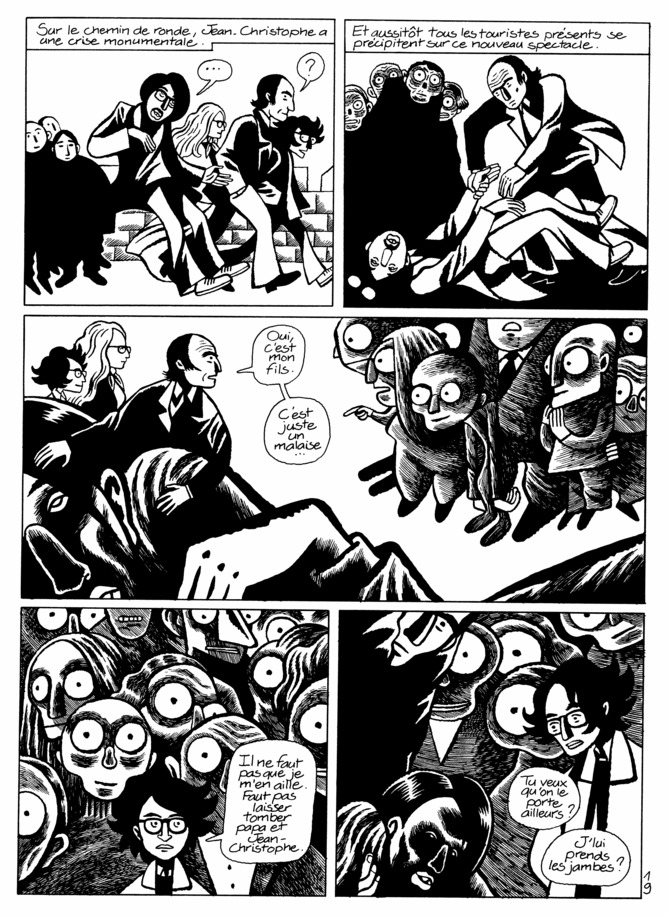

For example, in one passage, we become aware of the transgressive potential of “looking”. While on a family holiday, Jean-Christophe suffers a seizure. The authorial caption recalls: “[a]ll the tourists rush up, eager to enjoy this new diversion”. The narrator, David, grapples with his own desire to disappear from this scene, before deciding to stay.

Engorged with excitement, the onlookers’ distorted eyes and bodies swarm the main action. The tension here is elevated when we notice Jean-Christophe’s body, which now takes up the entire width of the middle panel. By playing with the proportions of these different bodies B. conveys the claustrophobic impact of the crowd’s attention on B. and his family.

In turn, this scene also encourages us, more generally, to consider the ways in which we regard Jean-Christophe throughout the book.

Through the use of panels, comics offer windows into alternate worlds that the reader must digest individually, and as a whole. In doing so, readers possess a high degree of involvement in the story, amplified by the operation of the “gutter” – the space in between the panels – that provokes us to draw connections between the panels (or refuse to do so). Moreover, the physical arrangement of the panels across the page, their composition, and content, creates an interpretive pulse that orients our navigation of the text.

Finding a home

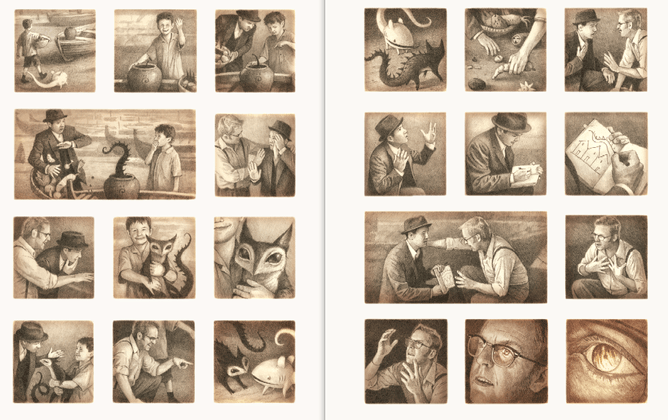

These features are also apparent in Shaun Tan’s remarkable and widely celebrated book The Arrival, which depicts the story of “the migrant”, who flees his homeland for a new place. In this place, he meets other individuals, many of whom also furnish stories of displacement. In one encounter, the migrant recalls a fearful memory from his place of origin with a new acquaintance. In response, the latter gestures to himself as the panels zoom towards his eye.

The last three panels in this sequence emphasise the commencement of the man’s story, positioning us to regard the upcoming narrative through “someone else’s eyes”. The double-page spread overleaf then plunges us into his memories. The size, shading and timing of the panels all contribute to our involvement in the story, and encourage our consideration of the characters we meet alongside the migrant.

In his introduction to Joe Sacco’s Palestine (1996), Edward Said recalled the fervour with which he consumed comics as a young reader, explaining that comics:

Comics encourage their readers to see again, and see differently. In a world that offers, on the one hand, an abundance of things to see and, on the other, frequently limited perspectives on what we see, and how our vision is framed, comics offer a modality that encourage seeing differently. This is particularly important when it comes to depicting marginalised individuals and cultural groups.

In cultures where appearances often count for more than they should, comics create new ways of seeing the world.

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

Relying on basic materials such as pencil and paper, cartoon and comics artists can readily respond to political and social issues; at their most impressive they draw out worlds that tend to remain unobserved.

At the same time, our easy access to visual images can, at times, encourage a superficial consideration of their impact. While there is an ongoing tradition of photographic works serving to inform their viewers, the repetition of particular images can also stereotype its subjects in problematic ways.

In other words, seeing, by itself, is not enough. How and what we see is also at stake. I’d like to draw attention to two comics that encourage readers to engage with stories of difference: Epileptic (2005) by David B. and The Arrival (2006) by Shaun Tan.

Epileptic

Originally published in six volumes as L’Ascension du Haut-Mal (1996-2003), Epileptic is the English translation of David B.’s memoir of his experiences growing up with an older brother, Jean-Christophe, who suffers from epilepsy.

© 2011, David B. & L'Association L'Association

Rendered in black and white, B.’s lyrical, confronting, and meticulous drawings access the anger and grief that Jean-Christophe’s condition provokes for the narrator, his family, and for Jean-Christophe himself. B. does not excuse any of the characters, including himself, from scrutiny, and indeed this intimate portrait of a family life is what makes the book so compelling. The book also reflects on the privileges and pitfalls that accompany vision.

For example, in one passage, we become aware of the transgressive potential of “looking”. While on a family holiday, Jean-Christophe suffers a seizure. The authorial caption recalls: “[a]ll the tourists rush up, eager to enjoy this new diversion”. The narrator, David, grapples with his own desire to disappear from this scene, before deciding to stay.

© 2011, David B. & L'Association. L'Association

Engorged with excitement, the onlookers’ distorted eyes and bodies swarm the main action. The tension here is elevated when we notice Jean-Christophe’s body, which now takes up the entire width of the middle panel. By playing with the proportions of these different bodies B. conveys the claustrophobic impact of the crowd’s attention on B. and his family.

In turn, this scene also encourages us, more generally, to consider the ways in which we regard Jean-Christophe throughout the book.

Through the use of panels, comics offer windows into alternate worlds that the reader must digest individually, and as a whole. In doing so, readers possess a high degree of involvement in the story, amplified by the operation of the “gutter” – the space in between the panels – that provokes us to draw connections between the panels (or refuse to do so). Moreover, the physical arrangement of the panels across the page, their composition, and content, creates an interpretive pulse that orients our navigation of the text.

Finding a home

Shaun Tan – The Arrival.

These features are also apparent in Shaun Tan’s remarkable and widely celebrated book The Arrival, which depicts the story of “the migrant”, who flees his homeland for a new place. In this place, he meets other individuals, many of whom also furnish stories of displacement. In one encounter, the migrant recalls a fearful memory from his place of origin with a new acquaintance. In response, the latter gestures to himself as the panels zoom towards his eye.

The last three panels in this sequence emphasise the commencement of the man’s story, positioning us to regard the upcoming narrative through “someone else’s eyes”. The double-page spread overleaf then plunges us into his memories. The size, shading and timing of the panels all contribute to our involvement in the story, and encourage our consideration of the characters we meet alongside the migrant.

The Arrival by Shaun Tan, Lothian Children’s Books, an imprint of Hachette Australia, 2006.Hachette

In his introduction to Joe Sacco’s Palestine (1996), Edward Said recalled the fervour with which he consumed comics as a young reader, explaining that comics:

seemed to say what couldn’t otherwise be said, perhaps what wasn’t permitted to be said or imagined, defying the ordinary processes of thought, which are policed, shaped and re-shaped by all sorts of pedagogical as well as ideological pressures.

Comics encourage their readers to see again, and see differently. In a world that offers, on the one hand, an abundance of things to see and, on the other, frequently limited perspectives on what we see, and how our vision is framed, comics offer a modality that encourage seeing differently. This is particularly important when it comes to depicting marginalised individuals and cultural groups.

In cultures where appearances often count for more than they should, comics create new ways of seeing the world.

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

Limited-time offer: Big stories, small price. Keep independent media alive. Become a Scroll member today!

Our journalism is for everyone. But you can get special privileges by buying an annual Scroll Membership. Sign up today!