Will you still have your high school diploma at age 72?

That’s been the question raging in Nigeria for the last few weeks as supporters of incumbent president Goodluck Jonathan demand his opponent produce proof he indeed did graduate. Retired general Muhammadu Buhari took to Twitter ‒ 20 times ‒ to defend himself.

The whole affair underscores this much: Nigerians place a premium on educational qualifications in all areas of life from employment prospects to marriage partner choices … and, yes, to presidents. In global cities, like London, Washington, and Atlanta, it’s not unheard of to bump into a degree-laden cab driver from Nigeria ‒ working on his PhD thesis at night. Of course, that pedigree comes up within minutes of conversation.

Tiger Mom writer Amy Chua included Nigerians in her controversial book, The Triple Package, as one of eight ethnic groups with a “superiority complex,” while also being fairly insecure and feeling the need to prove themselves.

“Nigerians earn doctorates at stunningly high rates … [these] groups have a cultural edge, which enables them to take advantage of opportunity far more than others.” Or as the New York Times noted in an article about Chua’s book:

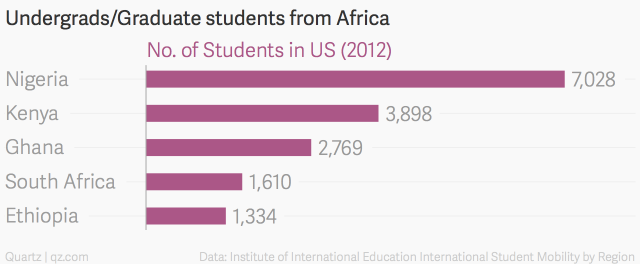

In the US, Nigeria has the largest number of students from any African nation ‒ just under 8,000 last year. They spent $241 million on getting undergraduate and post-graduate degrees in 2013 to 2014, according to Institute of International Education. The official figures have near tripled since 1996 to ’97 as more Nigerians seek quality higher education at a relatively exorbitant cost to studying at home; meanwhile, the number of universities in Nigeria has rocketed from just over 30 in the early 1990s to around 130 today. A degree is the best way to get a good middle-class job in a very competitive market.

For Nigerians it’s not only about high academic achievement and bragging rights. It’s also about being prepared to navigate a very bureaucratic society exacerbated in recent decades by rampant identity fraud. Most government bodies and businesses demand reams of paper evidence for everyday citizen roles.

As for Buhari, his degree came more than a half-century ago. He just doesn’t know where he put it. (Nigerian law requires that presidential candidates have passed their school certificate exams, which in the ’60s was administered by Cambridge University.) Buhari has other qualifications, though. He ran the country for nearly two years between 1984 and 1985. And he was a senior army officer for many years and has a post-graduate qualification in strategic studies from the U.S. War College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

Jonathan’s tactic has worked very well as a distraction from real issues. Buhari’s tweetstorm suggests the country best focus on those:

He eventually did find it, but not before his rivals claimed it was fake. Even Buhari’s young daughter Zahra came to her father’s defense on Twitter.

Jonathan, a former college professor, has a PhD in zoology ‒ an important part of his rags-to-the- presidential-palace riches tale when he ran four years ago. Some of Buhari’s supporters recently asked to see evidence of his doctorate thesis in an easily predictable tit-for-tat move.

Will a school certificate from 50 years ago even matter today? Amid entrenched poverty, rampant corruption, economic mismanagement, and an increasingly dangerous Islamic terrorist insurgency from Boko Haram, one thing is for sure: that piece of paper can hardly be the winning candidate’s sole qualification.

This article was originally published on qz.com.

That’s been the question raging in Nigeria for the last few weeks as supporters of incumbent president Goodluck Jonathan demand his opponent produce proof he indeed did graduate. Retired general Muhammadu Buhari took to Twitter ‒ 20 times ‒ to defend himself.

The whole affair underscores this much: Nigerians place a premium on educational qualifications in all areas of life from employment prospects to marriage partner choices … and, yes, to presidents. In global cities, like London, Washington, and Atlanta, it’s not unheard of to bump into a degree-laden cab driver from Nigeria ‒ working on his PhD thesis at night. Of course, that pedigree comes up within minutes of conversation.

Tiger Mom writer Amy Chua included Nigerians in her controversial book, The Triple Package, as one of eight ethnic groups with a “superiority complex,” while also being fairly insecure and feeling the need to prove themselves.

“Nigerians earn doctorates at stunningly high rates … [these] groups have a cultural edge, which enables them to take advantage of opportunity far more than others.” Or as the New York Times noted in an article about Chua’s book:

Nigerians make up less than 1 percent of the black population in the United States, yet in 2013 nearly one-quarter of the black students at Harvard Business School were of Nigerian ancestry; over a fourth of Nigerian-Americans have a graduate or professional degree, as compared with only about 11 percent of whites.

In the US, Nigeria has the largest number of students from any African nation ‒ just under 8,000 last year. They spent $241 million on getting undergraduate and post-graduate degrees in 2013 to 2014, according to Institute of International Education. The official figures have near tripled since 1996 to ’97 as more Nigerians seek quality higher education at a relatively exorbitant cost to studying at home; meanwhile, the number of universities in Nigeria has rocketed from just over 30 in the early 1990s to around 130 today. A degree is the best way to get a good middle-class job in a very competitive market.

For Nigerians it’s not only about high academic achievement and bragging rights. It’s also about being prepared to navigate a very bureaucratic society exacerbated in recent decades by rampant identity fraud. Most government bodies and businesses demand reams of paper evidence for everyday citizen roles.

As for Buhari, his degree came more than a half-century ago. He just doesn’t know where he put it. (Nigerian law requires that presidential candidates have passed their school certificate exams, which in the ’60s was administered by Cambridge University.) Buhari has other qualifications, though. He ran the country for nearly two years between 1984 and 1985. And he was a senior army officer for many years and has a post-graduate qualification in strategic studies from the U.S. War College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

Jonathan’s tactic has worked very well as a distraction from real issues. Buhari’s tweetstorm suggests the country best focus on those:

15/ And although the ruling party may want to wish this away, the issue in this campaign cannot be my certificate which I obtained 53...

— GMB Campaign Office (@GMBOffice) January 21, 201516/ ...years ago. The issues are the scandalous level of unemployment of millions of our young people, the state of insecurity, the...

— GMB Campaign Office (@GMBOffice) January 21, 2015He eventually did find it, but not before his rivals claimed it was fake. Even Buhari’s young daughter Zahra came to her father’s defense on Twitter.

If school certificate defines a good president, don't you think GEJ's PhD certificate ought to have fought insecurity & corruption.

— Miss Zahra (APC) (@Zahra_Buhari) January 28, 2015Jonathan, a former college professor, has a PhD in zoology ‒ an important part of his rags-to-the- presidential-palace riches tale when he ran four years ago. Some of Buhari’s supporters recently asked to see evidence of his doctorate thesis in an easily predictable tit-for-tat move.

Will a school certificate from 50 years ago even matter today? Amid entrenched poverty, rampant corruption, economic mismanagement, and an increasingly dangerous Islamic terrorist insurgency from Boko Haram, one thing is for sure: that piece of paper can hardly be the winning candidate’s sole qualification.

This article was originally published on qz.com.

Buy an annual Scroll Membership to support independent journalism and get special benefits.

Our journalism is for everyone. But you can get special privileges by buying an annual Scroll Membership. Sign up today!