After a prolonged delay, Delhi has introduced free Wi-Fi at its premier shopping hubs of Connaught Place and Khan Market. But this access, while in consonance with Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s vision of a Digital India, has raised concerns about privacy.

The Wi-Fi, accessible on mobile phones and laptops, is free for the first 20 minutes, after which a user can purchase a recharge from the various outlets in the areas. The facility, though new, has been a hit, particularly with students. But it comes ridden with risks. Using public Wi-Fi is like having a conversation in a public place. Would you broadcast a private talk for everyone to hear?

Even the government has been far from confident about public Wi-Fi in the past. “Insecure Wi-Fi networks are capable of being misused without any trail of user at later date,” wrote the Department of Telecom in a letter to internet service providers in 2009.

Prone to hackers

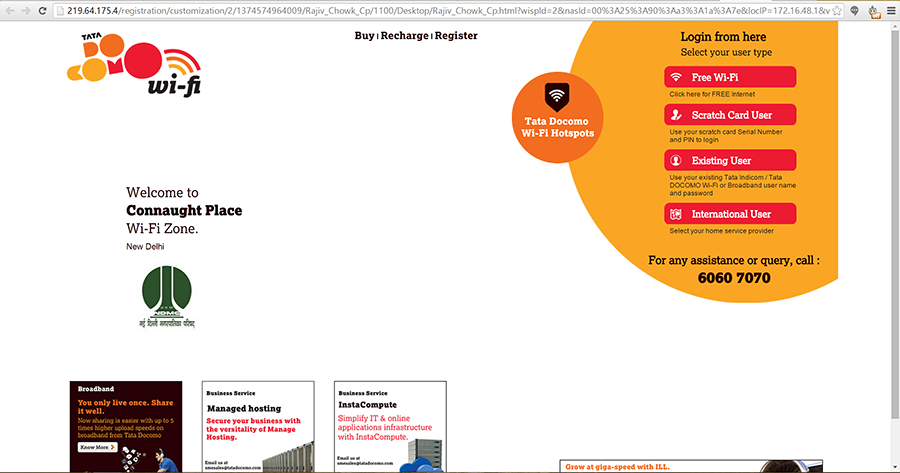

To provide the new service, the New Delhi Municipal Council has partnered with Tata Docomo in Connaught Place and with Vodafone in Khan Market. In Connaught Place at least, niggles surface the moment the Wi-Fi facility is logged into. Its terms and conditions cannot be accessed, the frequently asked questions are visible only after log in, and the contact us page does not load. A call to the Tata Docomo customer care can return the response that the fault is with the device.

Tata Teleservices also runs Wi-Fi services in other places like the Delhi international airport.

Still, the issue with the network is not reliability, but privacy. Large amounts of data on a public network are prime for theft by hackers. Also, the authorities have easier access to people’s browsing details and habits – which they have been known to abuse under the guise of hunting for terrorists. To get on to the Wi-Fi network in Delhi, a user has to give an email ID and a mobile phone number to get a onetime password. Beyond that, to recharge online, credit or debit information has to be provided.

Mohammad Chowdhury of PwC, while writing in Forbes India about public Wi-Fi systems, had said that a Wi-Fi provider can make money indirectly through “collection of the user’s demographic and location information which will be sold later for direct marketing”.

Worldwide concerns

Fears about public Wi-Fi are not new. Hyderabad planned to become a Wi-Fi enabled city by the year’s end, but experts raised fears about data theft and data collection by the government and service providers. The same concerns arose when Bangalore launched public Wi-Fi in January.

New York City’s recent plan to convert payphones into Wi-Fi hotspots also ran into problems. There were fears amongst privacy advocates that the network would become a tool to track citizens’ movements around the city. London, Paris and others have also come under scrutiny whenever plans were floated to deploy Wi-Fi networks for the public.

The Wi-Fi, accessible on mobile phones and laptops, is free for the first 20 minutes, after which a user can purchase a recharge from the various outlets in the areas. The facility, though new, has been a hit, particularly with students. But it comes ridden with risks. Using public Wi-Fi is like having a conversation in a public place. Would you broadcast a private talk for everyone to hear?

Even the government has been far from confident about public Wi-Fi in the past. “Insecure Wi-Fi networks are capable of being misused without any trail of user at later date,” wrote the Department of Telecom in a letter to internet service providers in 2009.

Prone to hackers

To provide the new service, the New Delhi Municipal Council has partnered with Tata Docomo in Connaught Place and with Vodafone in Khan Market. In Connaught Place at least, niggles surface the moment the Wi-Fi facility is logged into. Its terms and conditions cannot be accessed, the frequently asked questions are visible only after log in, and the contact us page does not load. A call to the Tata Docomo customer care can return the response that the fault is with the device.

Tata Teleservices also runs Wi-Fi services in other places like the Delhi international airport.

Still, the issue with the network is not reliability, but privacy. Large amounts of data on a public network are prime for theft by hackers. Also, the authorities have easier access to people’s browsing details and habits – which they have been known to abuse under the guise of hunting for terrorists. To get on to the Wi-Fi network in Delhi, a user has to give an email ID and a mobile phone number to get a onetime password. Beyond that, to recharge online, credit or debit information has to be provided.

Mohammad Chowdhury of PwC, while writing in Forbes India about public Wi-Fi systems, had said that a Wi-Fi provider can make money indirectly through “collection of the user’s demographic and location information which will be sold later for direct marketing”.

Worldwide concerns

Fears about public Wi-Fi are not new. Hyderabad planned to become a Wi-Fi enabled city by the year’s end, but experts raised fears about data theft and data collection by the government and service providers. The same concerns arose when Bangalore launched public Wi-Fi in January.

New York City’s recent plan to convert payphones into Wi-Fi hotspots also ran into problems. There were fears amongst privacy advocates that the network would become a tool to track citizens’ movements around the city. London, Paris and others have also come under scrutiny whenever plans were floated to deploy Wi-Fi networks for the public.

Buy an annual Scroll Membership to support independent journalism and get special benefits.

Our journalism is for everyone. But you can get special privileges by buying an annual Scroll Membership. Sign up today!