Prime Minister Narendra Modi might have swept almost everything before him during May's general election, but India’s electoral system left one stumbling block: the Rajya Sabha. Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party might have a commanding lead in the Lok Sabha, but it remains the minority in the Upper House, making it hard for legislation to be passed if there is solid opposition.

But that could change, starting with Maharashtra and Haryana. Over the course of Modi’s five-year tenure, 20 states are set to go to elections. Since most Rajya Sabha Members of Parliament, other than the few nominated ones, are elected by those in the legislatures of the states and the union territories, BJP victories in those assemblies could go a long way towards fixing the BJP’s poor position in the Upper House.

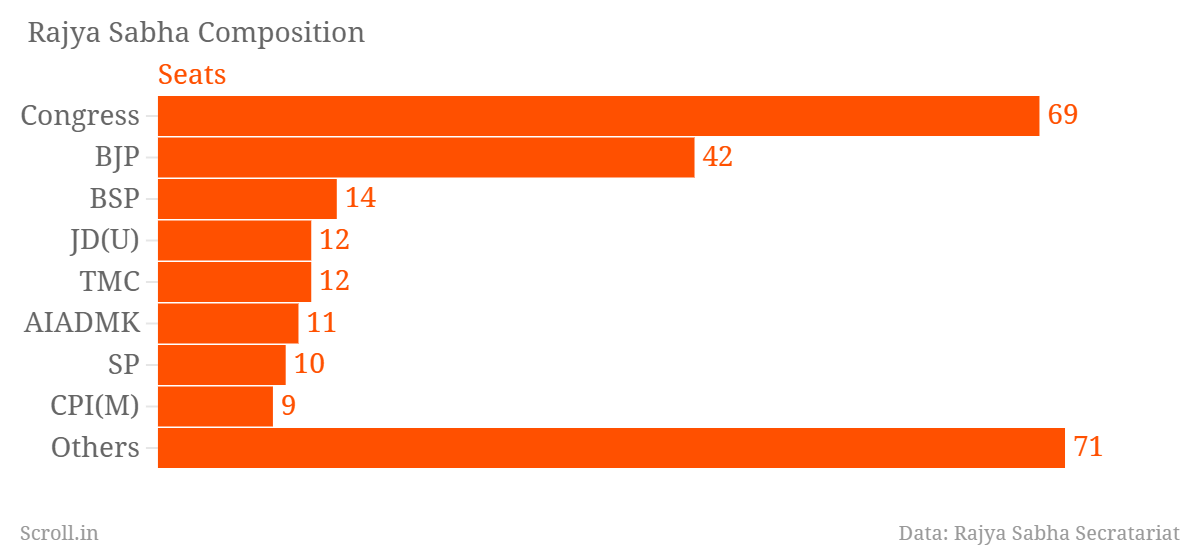

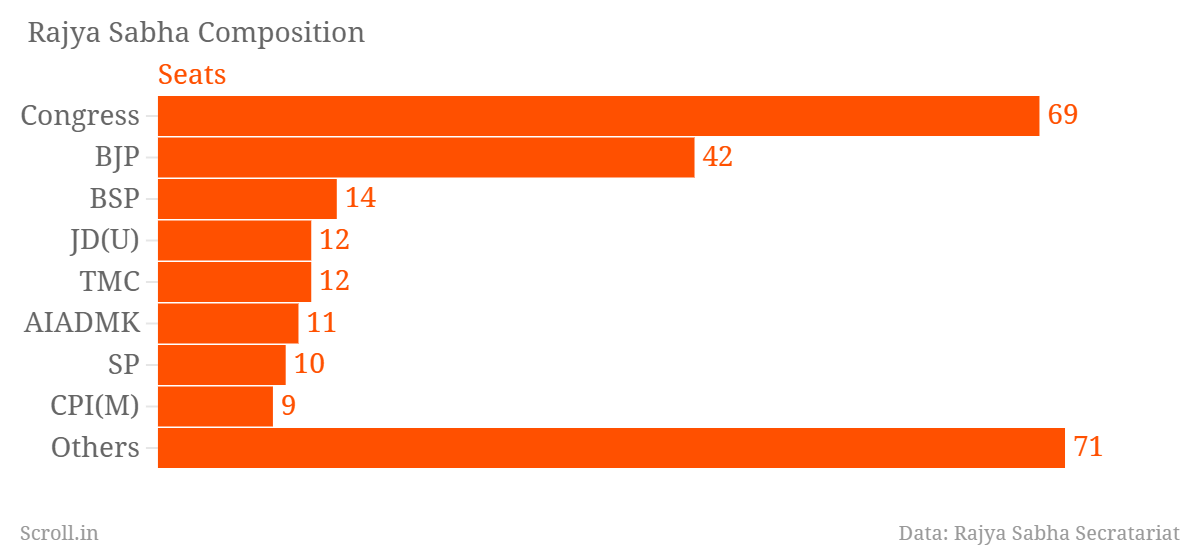

At the moment, the BJP has only 42 seats in the upper house. That might be a substantial amount in a 250-strong assembly, but the number is much smaller than the Congress’ 69 seats. In addition, the BJP is hemmed in by the presence of nearly 100 other members of other parties, whether part of the United Progressive Alliance or unaffiliated.

This means that it cannot push legislation through the Parliament, despite it’s massive position in the Lok Sabha, unless it wants to insist on joint sessions. Instead, it would much prefer to win seats in state assemblies over the next few years. If one includes the Rajya Sabha seats from all the states that are going to polls until Modi’s last year of his current term, the BJP could be in as commanding of a position in the upper house as they are in the Lok Sabha. A third of the Rajya Sabha’s seats will be up for grabs when elections are held next in 2016, followed by another round a couple of years later in 2018.

First off are Haryana and Maharashtra, where the BJP holds just two out of a total of 24 available Rajya Sabha seats. Maharashtra alone sends 19 MPs to the upper house, the second-largest number of MPs after Uttar Pradesh.

At the moment, 12 of the setas from the state are being held by the Congress and the Nationalist Congress Party, both of which are expected to be significantly hurt by anti-incumbency in Wednesday’s elections. Another three are held by the Shiv Sena, which might have left the BJP-led alliance in Maharashtra but has stayed in the National Democratic Alliance in the Centre, with the inclusion of one minister in the Union Cabinet.

Not all of the Maharashtra seats are up for grabs in 2016 or 2018, and much could happen with the BJP’s alliances as well as floor management between now and then. Yet the party under Amit Shah has made it clear, through its decisions to go it alone in without allies in both Maharashtra and Haryana – in one case jettisoning a 25-year-old partnership – that it wants to be able to stand on its own feet.

Modi said from the very beginning that, though he is only asking the people of India for 60 months to get something done, he is actually looking at a timeline of at least two prime ministerial terms: 10 years. His debut Independence Day speech in fact, featured an agenda for the next decade rather than just the next five years. If he is hoping to achieve that, it will be crucial for the party to take over states and gain the numbers it needs in the upper house to set its own legislative agenda.

But that could change, starting with Maharashtra and Haryana. Over the course of Modi’s five-year tenure, 20 states are set to go to elections. Since most Rajya Sabha Members of Parliament, other than the few nominated ones, are elected by those in the legislatures of the states and the union territories, BJP victories in those assemblies could go a long way towards fixing the BJP’s poor position in the Upper House.

At the moment, the BJP has only 42 seats in the upper house. That might be a substantial amount in a 250-strong assembly, but the number is much smaller than the Congress’ 69 seats. In addition, the BJP is hemmed in by the presence of nearly 100 other members of other parties, whether part of the United Progressive Alliance or unaffiliated.

This means that it cannot push legislation through the Parliament, despite it’s massive position in the Lok Sabha, unless it wants to insist on joint sessions. Instead, it would much prefer to win seats in state assemblies over the next few years. If one includes the Rajya Sabha seats from all the states that are going to polls until Modi’s last year of his current term, the BJP could be in as commanding of a position in the upper house as they are in the Lok Sabha. A third of the Rajya Sabha’s seats will be up for grabs when elections are held next in 2016, followed by another round a couple of years later in 2018.

First off are Haryana and Maharashtra, where the BJP holds just two out of a total of 24 available Rajya Sabha seats. Maharashtra alone sends 19 MPs to the upper house, the second-largest number of MPs after Uttar Pradesh.

At the moment, 12 of the setas from the state are being held by the Congress and the Nationalist Congress Party, both of which are expected to be significantly hurt by anti-incumbency in Wednesday’s elections. Another three are held by the Shiv Sena, which might have left the BJP-led alliance in Maharashtra but has stayed in the National Democratic Alliance in the Centre, with the inclusion of one minister in the Union Cabinet.

Not all of the Maharashtra seats are up for grabs in 2016 or 2018, and much could happen with the BJP’s alliances as well as floor management between now and then. Yet the party under Amit Shah has made it clear, through its decisions to go it alone in without allies in both Maharashtra and Haryana – in one case jettisoning a 25-year-old partnership – that it wants to be able to stand on its own feet.

Modi said from the very beginning that, though he is only asking the people of India for 60 months to get something done, he is actually looking at a timeline of at least two prime ministerial terms: 10 years. His debut Independence Day speech in fact, featured an agenda for the next decade rather than just the next five years. If he is hoping to achieve that, it will be crucial for the party to take over states and gain the numbers it needs in the upper house to set its own legislative agenda.

Limited-time offer: Big stories, small price. Keep independent media alive. Become a Scroll member today!

Our journalism is for everyone. But you can get special privileges by buying an annual Scroll Membership. Sign up today!