British India had for decades been a reservoir of cheap military labour available to be used by the imperial authorities, an ‘English barrack in the Oriental seas’. Unsurprisingly, when the war broke out in August 1914, the only overseas troops immediately available for deployment were those of the Indian Army. For India, the First World War came at a strange time. The nation was caught at a moment of growing nationalism, as evidenced by the swadeshi movement, that had nevertheless not yet reached such proportions as to snap the country’s loyalty to the Raj. As a result, when the King sent his message asking the ‘Princes and People of My Indian Empire’ to support the war effort the response was extremely enthusiastic – not just from the Indian princely states, but also the political bourgeoisie.

The British War Council agreed upon the Indian involvement in the war as early as 5 August 1914. Fighting imperial campaigns was not new for the Indian Army. It had previously fought not just on the Northwest frontiers of India, but also in places like China, Abyssinia, Perak, Egypt and Sudan. However, this was an important moment in the army’s history because it opened up the possibility of service in Europe. The deployment of Indian troops in Europe had thus far been avoided because the British were concerned about upholding ‘white prestige’. It was for this reason that the British had avoided using the Indian Army when in conflict with white enemies such as in the Boer War of 1899-1902. Having Indians kill white men in the battlefield could, after all, potentially upset the strict racial hierarchies and threaten the colonial machinery. Having had the experience of killing white men in the battlefield what would stop the Indian soldiers from thinking that they could turn on their masters? Still, necessity triumphed over ideology. Hardinge was keen to satisfy what he perceived as ‘advanced’ (that is, more politically demanding) Indian opinion that wanted greater involvement in the war, and urged an end to the colour bar that prevented Indian troops from serving in Europe. It was a position the King also came out in support of.

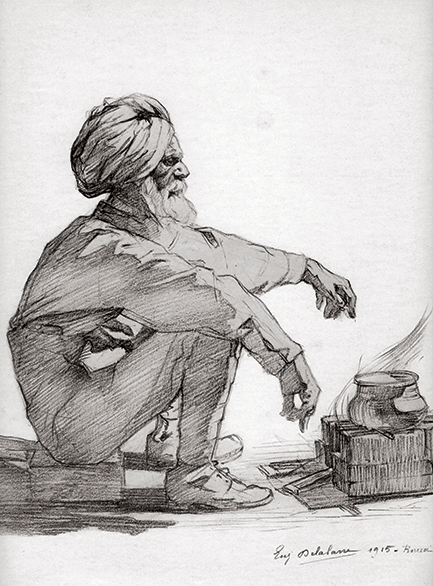

Once war had been declared, the mobilisation of troops began. By the end of the month, with the British troops on the Western Front suffering heavy setbacks, the war council decided that four Indian divisions, which formed Indian Expeditionary Force A, would be sent to the battlefields of Europe as reinforcement. At the same time smaller Expeditionary Forces B, C, and D were also being assembled for deployment in East Africa and Mesopotamia. In September 1914, the first Indian troops began reaching the scene of battle; they landed in Marseilles still in their tropical uniforms. The deployment of Indian soldiers to the war was met by a wave of celebratory remarks in newspapers in Britain. Perhaps the early months of the war were ripe to create a moment of sentimentality at the Empire coming together to fight the enemy. In a speech at the Indian Empire Club, the former Viceroy Lord Curzon described the arrival of the Indians as a ‘dramatic moment in the history of the Indian Empire’ and as a ‘landmark in our connection with India’.

In India too, a similar sentiment held sway as princely rulers and political leaders attempted to make the most of the opportunity offered by the war. For the various princely states (who still ruled about one-third of India in partnership with the Raj), the War was an opportunity to ingratiate themselves with the British. The Imperial Service Troops, forces raised by the princely states of the British Empire, were quickly placed at the disposal of the Viceroy. The 700-odd native princes also started to compete with each other with their offers of troops, money, and war goods. Sir Pertab Singh, the Regent of Jodhpur and other prominent leaders from states like Bikaner and Patiala volunteered to go to the front. The Maharaja of Mysore made a contribution of Rs.50 lakhs, the Maharaja of Baroda, Rs.5 lakhs. Gwalior offered an interest-free loan of Rs.50 lakhs in addition to troops, labourers, hospital ships, ambulances, motorcars, flotillas, horses, materials, food and clothes. The Begum of Bhopal sent 500 copies of the Koran and 1,487 copies of other religious tracts for Muslim soldiers. The Maharaja of Patiala sent romals to spread on the Adi Granth and chanani to Sikh soldiers in Germany. The Nizam of Hyderabad made a particularly munificent offer of six million rupees for the maintenance of two cavalry units in France. Even the smaller landlords and chieftains were not to be left behind – the Thakur of Bagli, for example, donated socks, shirts, mufflers, tobacco, cigarettes and chocolates for the Indian troops in East Africa, Mesopotamia and Egypt.

Leaders such as the Nizam of Hyderabad, the Nawab of Palanpur, the Begum of Bhopal, and Aga Khan also spoke publicly about the need for continuing loyalty from their subjects towards the British. This loyal support for the British cause became especially significant with the Ottoman Empire joining the War on the side of the Germans on 28 October 1914. The Ottoman Sultan was also considered the khalifaor religious leader by most South Asian Muslims and the presence of a large number of Muslim soldiers in the Indian Army raised British fears of desertion or worse, jihad, if these troops were made to fight against their Turkish religious brethren. An example of this continuing loyalty can be seen in the Begum of Bhopal’s speech at the Delhi War Conference in April 1918, where she stressed that, ‘Now that the war has entered upon a more intense phase we assure you that it will never be said that in this supreme crisis India when weighed in balance was found wanting.’ The British did recognize this outpouring of loyalty by the princely states – for example, the Nizam of Hyderabad was bestowed with the title ‘His Exalted Highness’. The famous Teen Murti statue that gave the Teen Murti Bhavan, (famous as the residence of the Commander-in-Chief of the Indian Army and later the Prime Minister of India, Jawaharlal Nehru) its name was built in 1922 in memory of the Indian soldiers from the princely states of Jodhpur, Hyderabad and Mysore who served in Palestine during the War.

Like the princely states, the nationalists of the time also had a vested interest in supporting the war effort, even if their motives were significantly different. The Indian National Congress pledged its support to the Allied cause and a number of other parties, including the All India Muslim League, agreed. Some of the leading political figures of the time campaigned extensively for the war effort and to boost recruitment. Such a response was partly built on the calculation that India’s strong role in the war would lead to political pay-offs. Indeed, as Annie Beasant, who had founded the India Home Rule League in 1916 wrote: ‘When the war is over… we cannot doubt that the King-Emperor will, as reward for her glorious defence of the Empire, pin upon her breast the jewelled medal of Self-Government within the Empire.’ It is important to note this emphasis on self-government within the confines of Empire, which made supporting Britain’s war aims doubly important. As the Tamil nationalist poet Subramania Bharthi wrote, ‘We want Home Rule. We advocate no violence. We shall always adopt peaceful and legal methods… In peace time we shall be uncompromising critics of England’s mistakes. But when trouble comes we shall unhesitatingly stand by her, and if necessary, defend her against her enemies.’ Even Mahatma Gandhi who was at the time in London, en route to India after his South African sojourn, noted at the beginning of the war that he thought that ‘England’s need should not be turned into our opportunity and that it was more becoming and far-sighted not to press our demands while the war lasted.’

But there was also another factor at play. Service in the war was seen by many Indians as a way to establish racial equality by proving that Indians were not lacking in courage or loyalty. The British recruited largely according to the so-called ‘Martial Races Theory’, which had at its core the belief that some Indians were inherently more warlike, bringing together indigenous notions of caste and the ideas of Social Darwinism. Few troops were recruited from eastern and southern India or urban areas because of the detrimental effects of ‘racial degeneracy’. The Western-educated were also excluded for their possibly politically subversive potential. The period of the war was marked by vociferous lobbying for the inclusion of a wider spectrum of Indians into the army. In particular, there was a constant demand to open up the officer ranks of the army to Indians by allowing them to become King’s Commissioned Officers (KCOs), which would enable them to take on official duties equivalent to a white officer. More broadly it was hoped that the need for men during the war would provide the opportunity to recapture martiality and martial traditions among non-martial Indians. While KCOs were not granted to Indians, the need for men as the war progressed led to recruitment out of necessity from not just non-martial communities but also marginalized and outcast communities such as tribals and untouchables.

For Bal Gangadhar Tilak, this broadening of recruitment offered many Indians the opportunity for military training that had so far been denied to them and was seen as a valuable instruction for the defence of India. Mahatma Gandhi, too, eventually came around to unconditional advocacy of enlistment (a position the historian Judith Brown had described as ‘a strange phenomenon for one who preached non-violence’). Writing an ‘Appeal for Enlistment’ leaflet, Gandhi wrote: ‘To bring about such a state of things we should have the ability to defend ourselves, that is, the ability to bear arms and to use them... If we want to learn the use of arms with the greatest possible dispatch, it is our duty to enlist ourselves in the army.’ For Gandhi, ‘Home Rule without military power was useless, and this was the best opportunity to get it’. An India ‘trained for fighting will be able to wrest freedom in a moment’, and with the strength gained on the battlefield ‘even fight the Empire, should it play foul with us’. This idea of the military service somehow bettering the Indian people was also taken up by the Congresswoman Sarojini Naidu, who wrote ‘Let young Indians, who are ready to die for India and to wipe from her bow the brand of slavery, rush to join the standing army, or to be more correct, India’s citizen army composed of cultured young men, of young men of tradition and ideals, men who burn with the shame of slavery in the hearts.’

Understanding this political milieu in India during the war can perhaps help one understand how easy it might have been for individual sepoys to get caught up in the fervour of war and how this might have been just as important a motivation in fighting as any economic benefit that would be accrued. Like most initial volunteers across the world, the war might have initially seemed a great adventure. They would get the chance to see vilayat, to meet people from other cultures, to fight alongside European soldiers. Some of the journeys the soldiers made would seem fantastic to people in India even today and one can only imagine just what a life-changing (and in some tragic instances, life-ending) journey this must have been for the more than a million Indians who experienced the war.

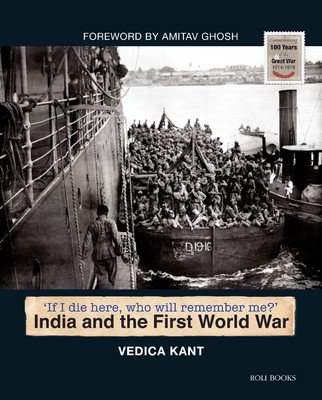

Excerpted with permission from If I Die Here, Who Will Remember Me: India and the First World War, published by Roli Books.

Limited-time offer: Big stories, small price. Keep independent media alive. Become a Scroll member today!

Our journalism is for everyone. But you can get special privileges by buying an annual Scroll Membership. Sign up today!