“Lantern Days Back in India? Power Plants Left with 2 Days of Coal Stock,” said the headline of a report published on the International Business Times website last week. It epitomised the panic over the decline in coal stocks that could soon plunge India into darkness. Even the sober Financial Times gravely wrote, “Asia’s third-largest economy faces a deepening fuel and power crisis.”

But government data shows that a greater threat to thermal power stations in India comes not from a lack of fuel supply but from technical failures.

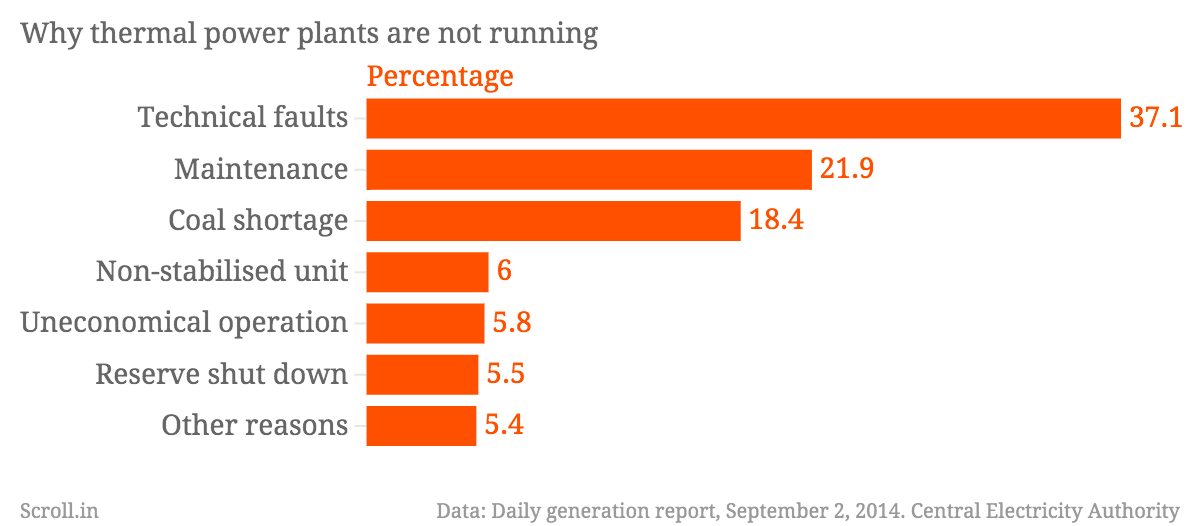

The Central Electricity Authority publishes daily reports on the output of power stations in India. The report for September 2 showed that 191 thermal power units were shut down on that day, which led to a loss of 51,006 MW of power.

Coal shortages accounted for less than one-fifth of the closed capacity. More than twice that capacity was lost because of technical snags. Other reasons – maintenance, reserve shut down, uneconomical operations – were responsible for the rest of the power generation losses.

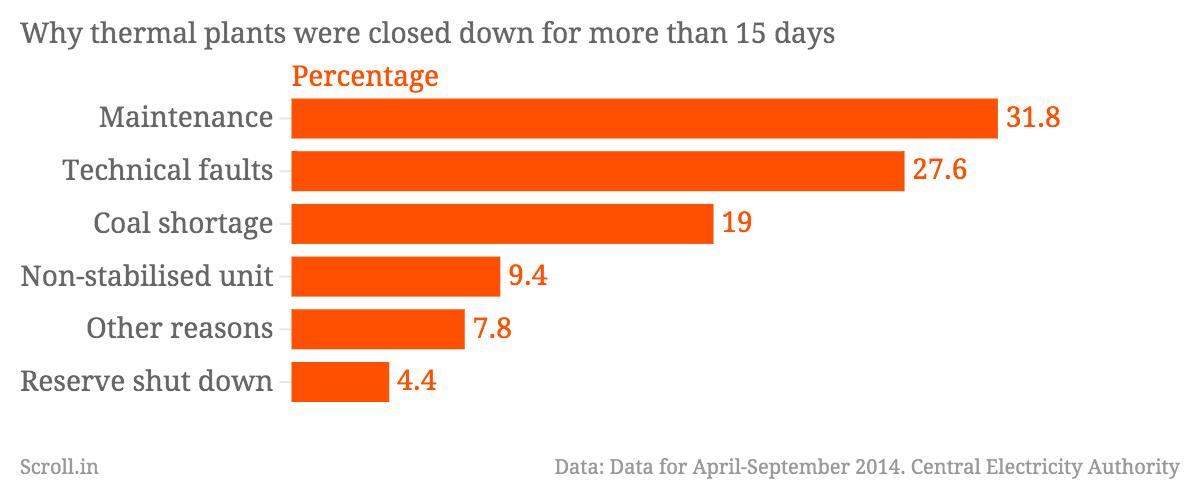

While this data gives a day’s snapshot, data for the last five months shows a similar pattern.

A report of the Central Electricity Authority shows that since April, 74 thermal power units closed down for more than 15 days. Again, coal shortage was responsible for less than 20% of the lost capacity.

Why is there such panic over coal supplies?

"Technical failure is unpredictable and unavoidable. But coal supply is something that you have planned for," said Ashok Khurana, director general of the Association of Power Producers, an industry body representing private power companies. "No power plant should close down for want of coal."

The recent panic over coal supplies has been set off by data for September 1 that showed that more than half of India’s thermal power plants had less than a week’s supply of coal.

This sounds more alarming than it actually might be.

Coal is not a one-time supply. It is a rolling stock. Power stations have agreements with coal companies which supply coal to them on a regular basis. Depending on their distance from coalmines, power stations maintain buffer stocks lasting 15 days to a month. When stocks dip to less than a week’s supply, it means the buffer stands depleted, but the plant will not come to grinding halt until the stocks fully run out.

A closer look at the data for thermal power stations shows that several large stations continue to run even though coal stocks are down to less than four days.

In other places, however, large coal stocks have piled up in stations that are shut for technical or economic reasons. Barauni power station in Bihar holds 55 days of coal stocks even though both of its units are closed. One shut down in 2006 and the other in 2012.

This indicates that part of the fuel shortage in power stations is caused by poor management of available coal supplies.

Most intriguingly, some plants have cited coal shortage as their reason for shutting down, though the data shows that they still have coal stocks for several days.

This leaves the data itself open to question. “The daily generation report is prepared by collating data that is entered directly into our system by the power stations,” said an official of the central electricity authority. “If they do not update the data correctly, we would not know.”

The lack of independent data often leads to disputes. In July, the chief of National Thermal Power Corporation, the leading power producing company, wrote to the coal minister saying coal stocks at six NTPC plants had reached "critical levels". At three plants, the stock would not last more than a day, he said. But Coal India, the company that supplies coal to NTPC, told NDTV that its had dispatched more than 100% of the agreed coal supplies to these plants. The channel reported that the electricity generation at the plants had risen by less than 2% while the coal dispatched by Coal India had gone up by 10%. So why had coal stocks hit critical levels? Either NTPC was lying or Coal India was – or the coal dispatched had simply been lost in transit.

The larger picture

Apart from poor management, the other reason why coal has come under pressure this year is the addition in thermal power generating capacity.

Between April 2013 and August 2014, India has added nearly 20,000 MW of thermal power capacity. The added capacity has enabled a 15% increase in power production between April and August this year compared to the same period last year.

Did coal production keep step with the rise in electricity generation? Last year, between April and August, Coal India Limited produced 167.32 million tonnes. This year, during the same period, it has produced 175.88 million tonnes. This is an increase of 8.56 million tonnes, which amounts to 5.1%.

While it is not possible to strictly compare the coal data and the electricity data because coal is also used in other industries like steel and cement, this does indicate that there is a shortfall of coal available for power generation.

But the extent of coal shortfall might not be as large as the newspaper headlines suggest. “There is a great deal of fear-mongering taking place,” said Sudiep Shrivastava, one of the lawyers in the coal case in the Supreme Court. He believes that commercial lobbies stand to gain from the perception of a massive coal shortfall in India. “They want to save coal mines that have been declared illegal from getting cancelled and they want to get new areas opened to coal mining.”

Whether or not that’s true, the data clearly shows that to ensure steady power generation, India needs to fix technical snags more than simply kicking up a dust over coal.

But government data shows that a greater threat to thermal power stations in India comes not from a lack of fuel supply but from technical failures.

The Central Electricity Authority publishes daily reports on the output of power stations in India. The report for September 2 showed that 191 thermal power units were shut down on that day, which led to a loss of 51,006 MW of power.

Coal shortages accounted for less than one-fifth of the closed capacity. More than twice that capacity was lost because of technical snags. Other reasons – maintenance, reserve shut down, uneconomical operations – were responsible for the rest of the power generation losses.

While this data gives a day’s snapshot, data for the last five months shows a similar pattern.

A report of the Central Electricity Authority shows that since April, 74 thermal power units closed down for more than 15 days. Again, coal shortage was responsible for less than 20% of the lost capacity.

Why is there such panic over coal supplies?

"Technical failure is unpredictable and unavoidable. But coal supply is something that you have planned for," said Ashok Khurana, director general of the Association of Power Producers, an industry body representing private power companies. "No power plant should close down for want of coal."

The recent panic over coal supplies has been set off by data for September 1 that showed that more than half of India’s thermal power plants had less than a week’s supply of coal.

This sounds more alarming than it actually might be.

Coal is not a one-time supply. It is a rolling stock. Power stations have agreements with coal companies which supply coal to them on a regular basis. Depending on their distance from coalmines, power stations maintain buffer stocks lasting 15 days to a month. When stocks dip to less than a week’s supply, it means the buffer stands depleted, but the plant will not come to grinding halt until the stocks fully run out.

A closer look at the data for thermal power stations shows that several large stations continue to run even though coal stocks are down to less than four days.

In other places, however, large coal stocks have piled up in stations that are shut for technical or economic reasons. Barauni power station in Bihar holds 55 days of coal stocks even though both of its units are closed. One shut down in 2006 and the other in 2012.

This indicates that part of the fuel shortage in power stations is caused by poor management of available coal supplies.

Most intriguingly, some plants have cited coal shortage as their reason for shutting down, though the data shows that they still have coal stocks for several days.

This leaves the data itself open to question. “The daily generation report is prepared by collating data that is entered directly into our system by the power stations,” said an official of the central electricity authority. “If they do not update the data correctly, we would not know.”

The lack of independent data often leads to disputes. In July, the chief of National Thermal Power Corporation, the leading power producing company, wrote to the coal minister saying coal stocks at six NTPC plants had reached "critical levels". At three plants, the stock would not last more than a day, he said. But Coal India, the company that supplies coal to NTPC, told NDTV that its had dispatched more than 100% of the agreed coal supplies to these plants. The channel reported that the electricity generation at the plants had risen by less than 2% while the coal dispatched by Coal India had gone up by 10%. So why had coal stocks hit critical levels? Either NTPC was lying or Coal India was – or the coal dispatched had simply been lost in transit.

The larger picture

Apart from poor management, the other reason why coal has come under pressure this year is the addition in thermal power generating capacity.

Between April 2013 and August 2014, India has added nearly 20,000 MW of thermal power capacity. The added capacity has enabled a 15% increase in power production between April and August this year compared to the same period last year.

Did coal production keep step with the rise in electricity generation? Last year, between April and August, Coal India Limited produced 167.32 million tonnes. This year, during the same period, it has produced 175.88 million tonnes. This is an increase of 8.56 million tonnes, which amounts to 5.1%.

While it is not possible to strictly compare the coal data and the electricity data because coal is also used in other industries like steel and cement, this does indicate that there is a shortfall of coal available for power generation.

But the extent of coal shortfall might not be as large as the newspaper headlines suggest. “There is a great deal of fear-mongering taking place,” said Sudiep Shrivastava, one of the lawyers in the coal case in the Supreme Court. He believes that commercial lobbies stand to gain from the perception of a massive coal shortfall in India. “They want to save coal mines that have been declared illegal from getting cancelled and they want to get new areas opened to coal mining.”

Whether or not that’s true, the data clearly shows that to ensure steady power generation, India needs to fix technical snags more than simply kicking up a dust over coal.

Limited-time offer: Big stories, small price. Keep independent media alive. Become a Scroll member today!

Our journalism is for everyone. But you can get special privileges by buying an annual Scroll Membership. Sign up today!