The hilly region of Kodagu, Karnataka's only district still without a rail connection, will finally get one, but not all residents are thrilled at the prospect.

The state's industrialists welcome the plan, but some locals fear a railway line could attract migrants and development projects to the detriment of the picturesque district, which is part of Coorg, a region with a history, culture and language distinct from the rest of the state. Natives call themselves Kodavas.

"We are not against development for the good of society," said Pratik Ponnanna, president of Yuva Codava, a youth group that is running an online petition against the railway line. "All we are saying is that instead of spending crores of rupees on the railway line, the government can build multi-speciality hospitals or better roads."

"We are not a right-wing group against migrants," he continued. "But we do not want to become like Assam. You can see how over the past few months, the Assamese people have clashed with Nagas and Bengalis. We have migrants in Kodagu too, but we live peacefully with them. Once the railway line comes, we might see more regionalism."

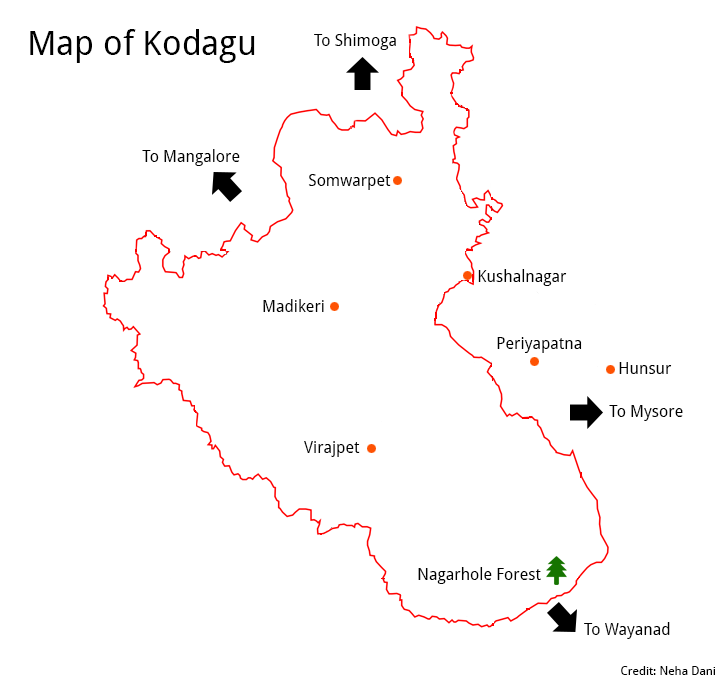

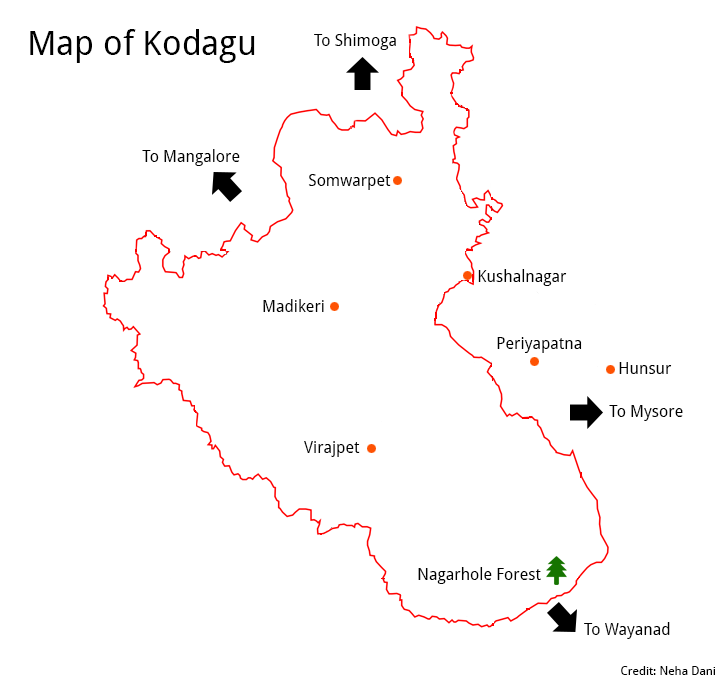

The line will go from Mysore to Kushalnagar, the last point in the plains, and onwards to Madikeri, Kodagu's headquarters. The railways have almost finished surveying the first segment and work will begin soon, Indian railway minister DV Sadananda Gowda said in his railway budget in June.

"We do not oppose a railway line in Kushalnagar because that is still in the plains, but we do not want Mysore to be linked to Madikeri," said Ponnanna.

Of 18 possible new lines being considered, Gowda named just three to survey, including Kodagu. This is not surprising because Gowda, a former chief minister of Karnataka, has close ties with Kodagu: his wife is from Guddehosur, near Kushalnagar.

In 2011, the Congress-led United Progressive Alliance-II government undertook a preliminary survey of the first part of the Kodagu line, from Mysore to Kushalnagar, but concluded that the route would be unprofitable and shelved the plan.

The UPA's railway ministry reconsidered its decision after Karnataka's chief minister, the BJP's BS Yeddyurappa, said his government would provide land to the railways for free and bear half the expenses. The ministry accepted this proposal, and the BJP-led National Democratic Front government launched the plan after taking over in May.

Distinct identity

The first attempt to lay a railway line to Kodagu goes back several decades. The Mysore Gazetteer noted as early as 1929 that a survey had been undertaken to verify the feasibility of a line between Mysore and Coorg. Then, as during the UPA-II's rule, the railways concluded that it would not be profitable because of Coorg’s hilly terrain.

Coorg was an independent kingdom until the British deposed its ruler in 1834. It remained a separately administered province until Independence, after which it became a province of the Indian Union. In 1956, while redefining states along linguistic lines, Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru decided to merge Coorg with the state of Mysore, although the Kodavas who live in Coorg do not speak Kannada.

Kodagu has since attempted to remain aloof from the rest of the state, keen on preserving what remains of the Kodava identity. This has caused some heartburn among people in the rest of the state.

"Despite Karnataka being a hub of education and technology in India, we were not connected to Madikeri,” said MC Dinesh, vice president of the Federation of Karnataka Chambers of Commerce and Industry. “Tourism will get a huge impetus [from the rail link]. They can run trains during the day so that people can see the fantastic landscape of Coorg.”

The influx of tourists is precisely what locals such as Ponnanna fear.

Business lobby

But the FKCCI, which is on the board of the South Western Railways, has been pitching for this railway connection since a Kodagu Investment Meet was held in December 2012.

"Large industries can’t come to Madikeri because it is hilly," said Dinesh, responding to fears that development will despoil the area's landscape. "Instead, we thought of making Coorg a hub for residential schools, like Ooty is. With a railway line, this will be possible.”

Pratap Simha, a Bharatiya Janata Party member of parliament from Mysore-Kodagu and former journalist, said the railway line would bring much-needed connectivity to the isolated region.

"The reason we are hell-bent on this project is that train fares are a third of bus fares," he said. "Bus connectivity is not good and it is too expensive for the common man. The people of Kodagu are demanding connectivity.”

The railway line would pass through Hulsur and Periyapatna outside Kodagu, both of which currently have no connections, he said.

Threat to elephants?

Almost the entire district of Kodagu lies in the highly bio-diverse Western Ghats. It is also home to a large roaming population of elephants. Over the past two years, as the plains to the east of Kodagu have become increasingly industrialised, elephants from places like Bandipur and Mudumalai have begun migrating towards the slopes, leading to a rise in elephant-human conflicts.

Environmentalists working in Kodagu contend that having a railway line will exacerbate this problem.

"The main concern for us is that the railway line will fragment an already fragmented landscape," said Tarun Cariappa, secretary of the Coorg Wildlife Society. "Herds of 16 to 17 elephants are already roaming around two kilometres from towns. At the moment, people are tolerating it, but at some point it will become an issue of their livelihoods."

Just last year, his group led agitations against a high-tension power line proposed to transport electricity from the Kudankulam nuclear power plant in Tamil Nadu to Kerala via a protected reserve area of Kodagu.

"They were planning to cut down 55,000 trees for that line, which could have gone through another route," said Cariappa. "Imagine how many they will cut for a railway line that will be so much broader."

But Dinesh said these concerns were misplaced. "Even if a few trees are cut down here and there, it is not as if they will not be planted elsewhere," he said. “Kodagu has always been a cry-baby district, saying that they are neglected. With the railway, more regional balancing will happen.”

The state's industrialists welcome the plan, but some locals fear a railway line could attract migrants and development projects to the detriment of the picturesque district, which is part of Coorg, a region with a history, culture and language distinct from the rest of the state. Natives call themselves Kodavas.

"We are not against development for the good of society," said Pratik Ponnanna, president of Yuva Codava, a youth group that is running an online petition against the railway line. "All we are saying is that instead of spending crores of rupees on the railway line, the government can build multi-speciality hospitals or better roads."

"We are not a right-wing group against migrants," he continued. "But we do not want to become like Assam. You can see how over the past few months, the Assamese people have clashed with Nagas and Bengalis. We have migrants in Kodagu too, but we live peacefully with them. Once the railway line comes, we might see more regionalism."

The line will go from Mysore to Kushalnagar, the last point in the plains, and onwards to Madikeri, Kodagu's headquarters. The railways have almost finished surveying the first segment and work will begin soon, Indian railway minister DV Sadananda Gowda said in his railway budget in June.

"We do not oppose a railway line in Kushalnagar because that is still in the plains, but we do not want Mysore to be linked to Madikeri," said Ponnanna.

Of 18 possible new lines being considered, Gowda named just three to survey, including Kodagu. This is not surprising because Gowda, a former chief minister of Karnataka, has close ties with Kodagu: his wife is from Guddehosur, near Kushalnagar.

In 2011, the Congress-led United Progressive Alliance-II government undertook a preliminary survey of the first part of the Kodagu line, from Mysore to Kushalnagar, but concluded that the route would be unprofitable and shelved the plan.

The UPA's railway ministry reconsidered its decision after Karnataka's chief minister, the BJP's BS Yeddyurappa, said his government would provide land to the railways for free and bear half the expenses. The ministry accepted this proposal, and the BJP-led National Democratic Front government launched the plan after taking over in May.

Distinct identity

The first attempt to lay a railway line to Kodagu goes back several decades. The Mysore Gazetteer noted as early as 1929 that a survey had been undertaken to verify the feasibility of a line between Mysore and Coorg. Then, as during the UPA-II's rule, the railways concluded that it would not be profitable because of Coorg’s hilly terrain.

Coorg was an independent kingdom until the British deposed its ruler in 1834. It remained a separately administered province until Independence, after which it became a province of the Indian Union. In 1956, while redefining states along linguistic lines, Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru decided to merge Coorg with the state of Mysore, although the Kodavas who live in Coorg do not speak Kannada.

Kodagu has since attempted to remain aloof from the rest of the state, keen on preserving what remains of the Kodava identity. This has caused some heartburn among people in the rest of the state.

"Despite Karnataka being a hub of education and technology in India, we were not connected to Madikeri,” said MC Dinesh, vice president of the Federation of Karnataka Chambers of Commerce and Industry. “Tourism will get a huge impetus [from the rail link]. They can run trains during the day so that people can see the fantastic landscape of Coorg.”

The influx of tourists is precisely what locals such as Ponnanna fear.

Business lobby

But the FKCCI, which is on the board of the South Western Railways, has been pitching for this railway connection since a Kodagu Investment Meet was held in December 2012.

"Large industries can’t come to Madikeri because it is hilly," said Dinesh, responding to fears that development will despoil the area's landscape. "Instead, we thought of making Coorg a hub for residential schools, like Ooty is. With a railway line, this will be possible.”

Pratap Simha, a Bharatiya Janata Party member of parliament from Mysore-Kodagu and former journalist, said the railway line would bring much-needed connectivity to the isolated region.

"The reason we are hell-bent on this project is that train fares are a third of bus fares," he said. "Bus connectivity is not good and it is too expensive for the common man. The people of Kodagu are demanding connectivity.”

The railway line would pass through Hulsur and Periyapatna outside Kodagu, both of which currently have no connections, he said.

Threat to elephants?

Almost the entire district of Kodagu lies in the highly bio-diverse Western Ghats. It is also home to a large roaming population of elephants. Over the past two years, as the plains to the east of Kodagu have become increasingly industrialised, elephants from places like Bandipur and Mudumalai have begun migrating towards the slopes, leading to a rise in elephant-human conflicts.

Environmentalists working in Kodagu contend that having a railway line will exacerbate this problem.

"The main concern for us is that the railway line will fragment an already fragmented landscape," said Tarun Cariappa, secretary of the Coorg Wildlife Society. "Herds of 16 to 17 elephants are already roaming around two kilometres from towns. At the moment, people are tolerating it, but at some point it will become an issue of their livelihoods."

Just last year, his group led agitations against a high-tension power line proposed to transport electricity from the Kudankulam nuclear power plant in Tamil Nadu to Kerala via a protected reserve area of Kodagu.

"They were planning to cut down 55,000 trees for that line, which could have gone through another route," said Cariappa. "Imagine how many they will cut for a railway line that will be so much broader."

But Dinesh said these concerns were misplaced. "Even if a few trees are cut down here and there, it is not as if they will not be planted elsewhere," he said. “Kodagu has always been a cry-baby district, saying that they are neglected. With the railway, more regional balancing will happen.”

Scroll has produced award-winning journalism despite violent threats, falling ad revenues and rising costs. Support our work. Become a member today.

In these volatile times, Scroll remains steadfastly courageous, nuanced and comprehensive. Become a Scroll Member and support our award-winning reportage, commentary and culture writing.