The Hindi crisis is in the news again. Many civil-service aspirants are protesting that the Union Public Service Commission examination puts those who take the test in Hindi at a disadvantage. But this controversy reveals a larger crisis facing Hindi, one much older and much more serious: a crisis of credibility.

A few days ago, a young Hindi literature critic posted Jawaharlal Nehru’s views about Hindi writers and journalists on his Facebook page. The provocation for the post was the Hindi versus English debate currently occupying the national mind and media space.

His post quoted passages from Nehru's Meri Kahani (An Autobiography) which suggested that Hindi literature has been in a crisis ever since India's first prime minister called Hindi writers a bunch of shallow short-tempered hacks marred by a debilitating inferiority complex. Hindi writers, Nehru said, behaved like courtiers aloof from the reality of the masses. They wrote only for a very small circle.

Nehru made these remarks at a time when some of the greatest writers in Hindi – Jai Shankar Prasad, Acharya Ramachandra Shukl, Mahadevi Verma, Prem Chand, Suryakant Tripathi Nirala – were all active. But Nehru did not trust them. Hindi critics and writers, he wrote, indulged in the worst form of abusive mud-slinging, wasting the literary possibilities offered by the land and people of India.

It won't be surprising if Nehru's words seem to ring true for a large section of readers exposed mostly to English literature and criticism. But there is, on the contrary, a lot of hope for Hindi. As long as there are writers obstinate enough to bare their souls, Hindi will not be overshadowed. Its young writers are writing not just for deeply personal reasons, they are also pushing the limits of what can be said and by whom.

A new voice

Anil Yadav is one such writer, one of the finest voices to have exploded on the scene in the past few years.

His first book was a collection of short stories, titled Nagar Vadhuyen Akhbar Nahi Padti (City Brides Don't Read the Newspapers). It was published in 2011.

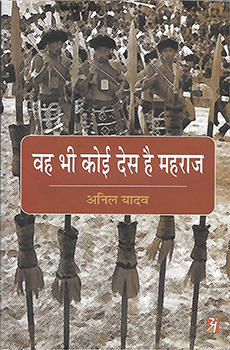

His second and most recent work, which came out last year, Wah Bhi Koi Desh Hai Maharaj (Is That Even a Country, My Lord!), an account of his travels in the North East in the early 2000s, has taken the Hindi literary scene by storm. Largely ignored by a Bollywood-obsessed media, the book is all the rage among the depleting mass of Hindi readers and is on its way to attaining cult status.

The 158-page book is the story of India’s most neglected region told by the narrative voice of a poor, petulant reporter. Anyone who doubts the power of Hindi must read it.

Books on the North East are usually written for a largely Western audience by fellowship-holders, retired newspaper editors or sincere foreign correspondents. The writers, almost as a rule, are member of the upper classes who have been born in the the North East or who have been led there by an academic interest. All of them write in English. Stripped of the exotic, the North East in Wah Bhi Koi Desh Hai Maharaj appears bare, burnt and betrayed.

The book opens with a striking image: dried urine and vomit peeling off the window frames of the stagnant Brahmaputra Express, bandicoots, some of them bigger than cats, roaming its innards. Yadav stands at the platform looking at the train, enduring the bites of vicious mosquitoes, contemplating the journey ahead of him.

He doesn't have a plan, which in hindsight, Yadav agrees, is often better than actually having one, no matter how meticulous. A book wasn’t even on the cards when he embarked on his trip to the North East in November 2000.

“All I wanted was to make a name for myself as a journalist by writing stories from the North East that no one was prepared to write,” he wrote in the book. It turned out that the stories no one wanted to write were exactly the kind of stories no one wanted to publish. “It was as if the place was off the map,” he wrote.

He knew next to nothing about the place he was going to write about although did have a connection. His father, an air force employee, had once been posted in Dibrugarh, Assam, although Yadav had never lived there.

His partner in crime and the financier of the trip, and a much-mentioned character in the book, is his friend Shashwat, who remains unaffected by what he sees around him till the shock of what it is like living in the North East finally hits him. He first undergoes a serious bout of silent depression followed by grave panic attacks. Finally, one day he ups and leaves. Yadav is now all alone and stone-broke. He has to hitchhike to complete the rest of his journey.

The doer

Yadav's voice is sincere to the point of being tragic. This sincerity, reminiscent of David Foster Wallace, sets him apart from his contemporaries. Over the phone, Yadav speaks softly, pausing every now and then.

Writing is more than a way of life, he says. His voice reveals a deep yet desperate desire to closely examine one's life all the time to see if it stands up to one’s principles. If it does, he can write, otherwise he can't.

Yadav’s image in literary circles is that of a maverick, a man of principles, a doer more than a talker. As a student leader at Banaras Hindu University in the late 1980s, he was a card-carrying member of the Communist Party of India (M). He turned to journalism after he graduated in 1991 and moved on to full-time writing at the end of the decade.

Last year, he courted a lot of controversy when he interviewed the famous writer Rajendra Yadav about women writers and sex. What came out of the interview was explosive: Rajendra Yadav confessed to having sexual feelings for a female writer whom everyone thought he loved like his daughter.

NGO activists threatened to take Anil Yadav to court for the interview, which Yadav published on Kabadkhaana, a Hindi literary blog. “I hate the silence on sexuality, especially among writers," he said. "Why can’t people be open about what they feel?”

Weh Bhi Koi Desh Hai Maharaj is as much a book about the North East as it is a discourse on fundamental elements like land and language that constitute our identity. His voice is fresh, his style hardcore, his language mellifluous. In one stunning passage, eschewing any explanation, the narrative meditatively lingers on Nagaland, juxtaposing its fight for independence with the bloody wars between its numerous tribes.

The uses of anger

At 45, Yadav is angry in a healthy sort of way. Sequestered in a Himachal village, he is working on his first novel, which he hopes will be out in the middle of next year. He has a mobile phone, but no internet connectivity. “I don’t have to worry about anything here," he said. "All I do is write.”

Yadav had planned on cooking for himself but as soon as he moved into the village, a family took him in. “They have looked after me like a son,” he said. To augment the silence, he meditates. To relax, he plays volleyball with boys from the village.

Before dinner he has a drink. For the rest of the time, he writes, and reads. He comes across like a character from a Roberto Bolaño book, a reclusive writer with an untrained mind, someone like Hans Reiter from 2666. His soft voice, firm but not intimidating, betrayed no trace of the anger that sometimes burns on the pages of his writing.

Yadav has a bone to pick with most of his contemporaries. Some of them happen to be well-known names in Hindi literature, such as Uday Prakash and Vinod Kumar Shukl.

“I don’t like Uday Prakash’s work," Yadav said bluntly. "It is tough for me to like any writer who doesn’t live the life he writes. He claims to be a Dalit writer but behaves like a Brahminised one. He’s a hypocrite whom I have no patience for.”

This candid attitude bodes well for Hindi at a time when every writer secretly wishes for some form of government patronage. Immersed in this book, readers feel like Insiders and outsiders at the same time as they become familiar with a land and a language that are supposedly theirs.

As long as Anil Yadav writes, there is hope for Hindi, no matter how loud the noise against it gets.

A few days ago, a young Hindi literature critic posted Jawaharlal Nehru’s views about Hindi writers and journalists on his Facebook page. The provocation for the post was the Hindi versus English debate currently occupying the national mind and media space.

His post quoted passages from Nehru's Meri Kahani (An Autobiography) which suggested that Hindi literature has been in a crisis ever since India's first prime minister called Hindi writers a bunch of shallow short-tempered hacks marred by a debilitating inferiority complex. Hindi writers, Nehru said, behaved like courtiers aloof from the reality of the masses. They wrote only for a very small circle.

Nehru made these remarks at a time when some of the greatest writers in Hindi – Jai Shankar Prasad, Acharya Ramachandra Shukl, Mahadevi Verma, Prem Chand, Suryakant Tripathi Nirala – were all active. But Nehru did not trust them. Hindi critics and writers, he wrote, indulged in the worst form of abusive mud-slinging, wasting the literary possibilities offered by the land and people of India.

It won't be surprising if Nehru's words seem to ring true for a large section of readers exposed mostly to English literature and criticism. But there is, on the contrary, a lot of hope for Hindi. As long as there are writers obstinate enough to bare their souls, Hindi will not be overshadowed. Its young writers are writing not just for deeply personal reasons, they are also pushing the limits of what can be said and by whom.

A new voice

Anil Yadav is one such writer, one of the finest voices to have exploded on the scene in the past few years.

His first book was a collection of short stories, titled Nagar Vadhuyen Akhbar Nahi Padti (City Brides Don't Read the Newspapers). It was published in 2011.

His second and most recent work, which came out last year, Wah Bhi Koi Desh Hai Maharaj (Is That Even a Country, My Lord!), an account of his travels in the North East in the early 2000s, has taken the Hindi literary scene by storm. Largely ignored by a Bollywood-obsessed media, the book is all the rage among the depleting mass of Hindi readers and is on its way to attaining cult status.

The 158-page book is the story of India’s most neglected region told by the narrative voice of a poor, petulant reporter. Anyone who doubts the power of Hindi must read it.

Books on the North East are usually written for a largely Western audience by fellowship-holders, retired newspaper editors or sincere foreign correspondents. The writers, almost as a rule, are member of the upper classes who have been born in the the North East or who have been led there by an academic interest. All of them write in English. Stripped of the exotic, the North East in Wah Bhi Koi Desh Hai Maharaj appears bare, burnt and betrayed.

The book opens with a striking image: dried urine and vomit peeling off the window frames of the stagnant Brahmaputra Express, bandicoots, some of them bigger than cats, roaming its innards. Yadav stands at the platform looking at the train, enduring the bites of vicious mosquitoes, contemplating the journey ahead of him.

He doesn't have a plan, which in hindsight, Yadav agrees, is often better than actually having one, no matter how meticulous. A book wasn’t even on the cards when he embarked on his trip to the North East in November 2000.

“All I wanted was to make a name for myself as a journalist by writing stories from the North East that no one was prepared to write,” he wrote in the book. It turned out that the stories no one wanted to write were exactly the kind of stories no one wanted to publish. “It was as if the place was off the map,” he wrote.

He knew next to nothing about the place he was going to write about although did have a connection. His father, an air force employee, had once been posted in Dibrugarh, Assam, although Yadav had never lived there.

His partner in crime and the financier of the trip, and a much-mentioned character in the book, is his friend Shashwat, who remains unaffected by what he sees around him till the shock of what it is like living in the North East finally hits him. He first undergoes a serious bout of silent depression followed by grave panic attacks. Finally, one day he ups and leaves. Yadav is now all alone and stone-broke. He has to hitchhike to complete the rest of his journey.

The doer

Yadav's voice is sincere to the point of being tragic. This sincerity, reminiscent of David Foster Wallace, sets him apart from his contemporaries. Over the phone, Yadav speaks softly, pausing every now and then.

Writing is more than a way of life, he says. His voice reveals a deep yet desperate desire to closely examine one's life all the time to see if it stands up to one’s principles. If it does, he can write, otherwise he can't.

Yadav’s image in literary circles is that of a maverick, a man of principles, a doer more than a talker. As a student leader at Banaras Hindu University in the late 1980s, he was a card-carrying member of the Communist Party of India (M). He turned to journalism after he graduated in 1991 and moved on to full-time writing at the end of the decade.

Last year, he courted a lot of controversy when he interviewed the famous writer Rajendra Yadav about women writers and sex. What came out of the interview was explosive: Rajendra Yadav confessed to having sexual feelings for a female writer whom everyone thought he loved like his daughter.

NGO activists threatened to take Anil Yadav to court for the interview, which Yadav published on Kabadkhaana, a Hindi literary blog. “I hate the silence on sexuality, especially among writers," he said. "Why can’t people be open about what they feel?”

Weh Bhi Koi Desh Hai Maharaj is as much a book about the North East as it is a discourse on fundamental elements like land and language that constitute our identity. His voice is fresh, his style hardcore, his language mellifluous. In one stunning passage, eschewing any explanation, the narrative meditatively lingers on Nagaland, juxtaposing its fight for independence with the bloody wars between its numerous tribes.

The uses of anger

At 45, Yadav is angry in a healthy sort of way. Sequestered in a Himachal village, he is working on his first novel, which he hopes will be out in the middle of next year. He has a mobile phone, but no internet connectivity. “I don’t have to worry about anything here," he said. "All I do is write.”

Yadav had planned on cooking for himself but as soon as he moved into the village, a family took him in. “They have looked after me like a son,” he said. To augment the silence, he meditates. To relax, he plays volleyball with boys from the village.

Before dinner he has a drink. For the rest of the time, he writes, and reads. He comes across like a character from a Roberto Bolaño book, a reclusive writer with an untrained mind, someone like Hans Reiter from 2666. His soft voice, firm but not intimidating, betrayed no trace of the anger that sometimes burns on the pages of his writing.

Yadav has a bone to pick with most of his contemporaries. Some of them happen to be well-known names in Hindi literature, such as Uday Prakash and Vinod Kumar Shukl.

“I don’t like Uday Prakash’s work," Yadav said bluntly. "It is tough for me to like any writer who doesn’t live the life he writes. He claims to be a Dalit writer but behaves like a Brahminised one. He’s a hypocrite whom I have no patience for.”

This candid attitude bodes well for Hindi at a time when every writer secretly wishes for some form of government patronage. Immersed in this book, readers feel like Insiders and outsiders at the same time as they become familiar with a land and a language that are supposedly theirs.

As long as Anil Yadav writes, there is hope for Hindi, no matter how loud the noise against it gets.

Limited-time offer: Big stories, small price. Keep independent media alive. Become a Scroll member today!

Our journalism is for everyone. But you can get special privileges by buying an annual Scroll Membership. Sign up today!