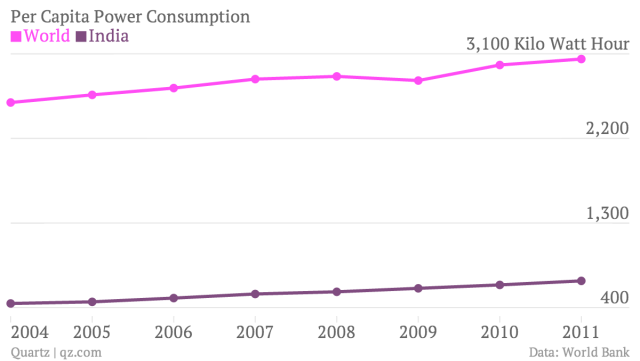

India’s per capita power consumption is among the lowest in the world and the country needs sweeping reforms if it wants to provide electricity to all by 2019, says the World Bank. Currently, a quarter of the population, some 300 million people, live without access to electricity.

A new World Bank report, conducted at the request of the Government of India, has identified electricity distribution to the end consumer as the sector’s debilitating point. According to the Bank, some of the reforms that can fix India’s power mess are: freeing utilities and regulators from government interference, increasing accountability and enhancing competition in the sector.

India ranks poorly on the ease of getting a power connection. For a typical commercial establishment to get a power connection, it requires seven different procedures and 67 days in India. In comparison, this takes 28 days in China, 35 in Thailand, 36 in Singapore, and 41 in Hong Kong. India ranks 99th in the world on this scale.

More than 28 million Indians have annually gained access to electricity in the first decade of this century. Annual per capita power sector consumption is around 800 kWh.

The sector is in delicate financial state and the total accumulated losses stood at Rs 1.14 trillion ($25 billion) in 2011. These losses are concentrated among distribution companies and bundled utilities – state electricity boards and the state power departments.

The losses have led to heavy borrowing and right now the power sector’s debt is as much as 5% of India’s GDP. Over the last twenty years, it has been bailed out in 2001 and in 2011 by the central government. In 2001, the bailout package was more than the size of the GDP of Nepal. In 2011, the money it cost the exchequer to write off power sector losses would have paid for 15,000 hospitals and 123,000 schools, the Bank estimated.

“The crux of the matter is that distribution utilities are not run on commercial lines. Despite corporatisation, their boards remain state-dominated and are rarely evaluated on performance,” said Sheoli Pargal, economic advisor at World Bank and author of the report. “And a history of state rescues has meant that lenders do not pressure distributors to improve their operational and financial performance, expecting to be paid back by the state.”

This post originally appeared on Qz.com. It has been edited.

A new World Bank report, conducted at the request of the Government of India, has identified electricity distribution to the end consumer as the sector’s debilitating point. According to the Bank, some of the reforms that can fix India’s power mess are: freeing utilities and regulators from government interference, increasing accountability and enhancing competition in the sector.

India ranks poorly on the ease of getting a power connection. For a typical commercial establishment to get a power connection, it requires seven different procedures and 67 days in India. In comparison, this takes 28 days in China, 35 in Thailand, 36 in Singapore, and 41 in Hong Kong. India ranks 99th in the world on this scale.

More than 28 million Indians have annually gained access to electricity in the first decade of this century. Annual per capita power sector consumption is around 800 kWh.

The sector is in delicate financial state and the total accumulated losses stood at Rs 1.14 trillion ($25 billion) in 2011. These losses are concentrated among distribution companies and bundled utilities – state electricity boards and the state power departments.

The losses have led to heavy borrowing and right now the power sector’s debt is as much as 5% of India’s GDP. Over the last twenty years, it has been bailed out in 2001 and in 2011 by the central government. In 2001, the bailout package was more than the size of the GDP of Nepal. In 2011, the money it cost the exchequer to write off power sector losses would have paid for 15,000 hospitals and 123,000 schools, the Bank estimated.

“The crux of the matter is that distribution utilities are not run on commercial lines. Despite corporatisation, their boards remain state-dominated and are rarely evaluated on performance,” said Sheoli Pargal, economic advisor at World Bank and author of the report. “And a history of state rescues has meant that lenders do not pressure distributors to improve their operational and financial performance, expecting to be paid back by the state.”

This post originally appeared on Qz.com. It has been edited.

Limited-time offer: Big stories, small price. Keep independent media alive. Become a Scroll member today!

Our journalism is for everyone. But you can get special privileges by buying an annual Scroll Membership. Sign up today!