On Thursday, Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam Chief M. Karunanidhi criticised an order by the Home Ministry advising government officials to accord priority to Hindi when writing letters and on social media.

Karunanidhi said that the order was an attempt to "impose Hindi against one's wish". He said it should "be seen as an attempt to treat non-Hindi speakers as second class citizens".

However, home minister Rajnath Singh clarified in a tweet, "The Home Ministry is of the view that all Indian languages are important. The Ministry is committed to promote all languages of the country."

On the social media, the directive found several supporters. Some claimed that the order was justified because Hindi is, after all, India's national language. It isn't: it's one of India's two official language, along with English.

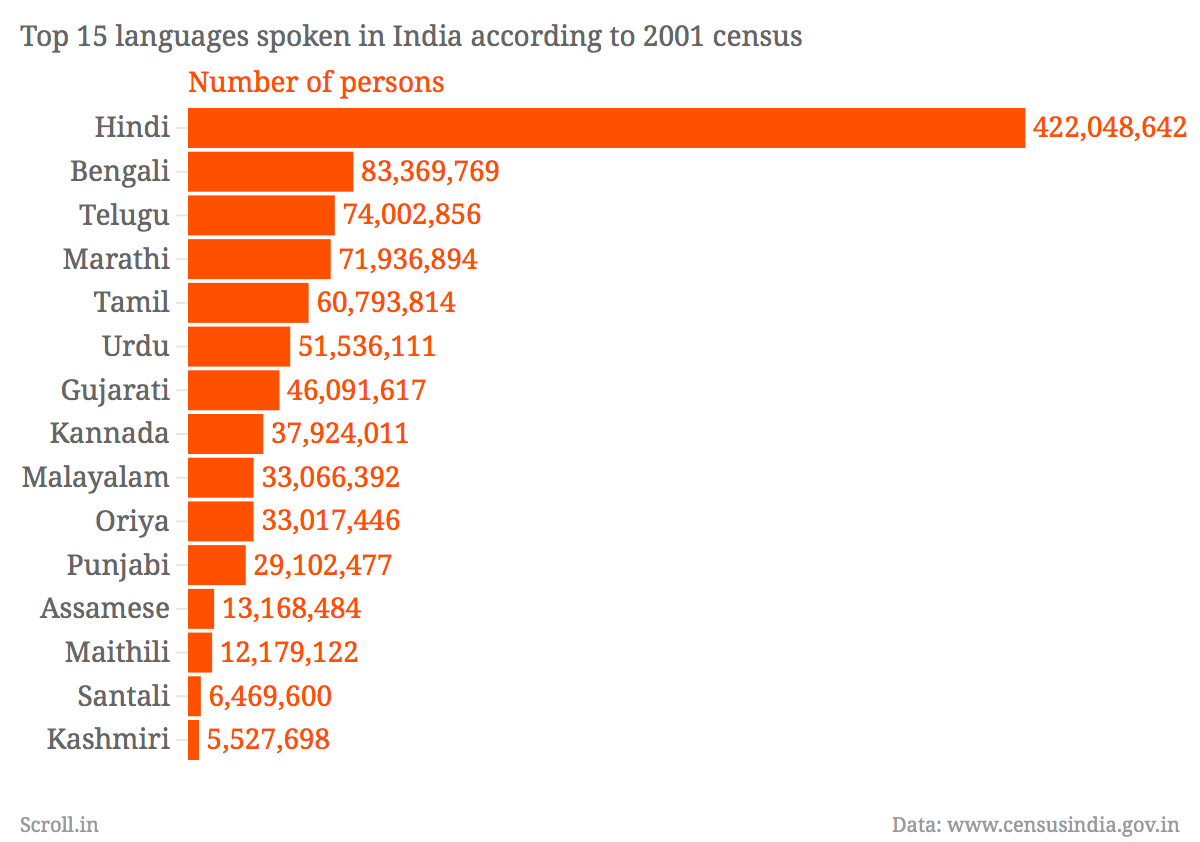

Others made a majoritarian argument, suggesting that Hindi should be made the national language because it is the mother tongue of about 45% of all Indians.

That, after all, is what the Census of India says.

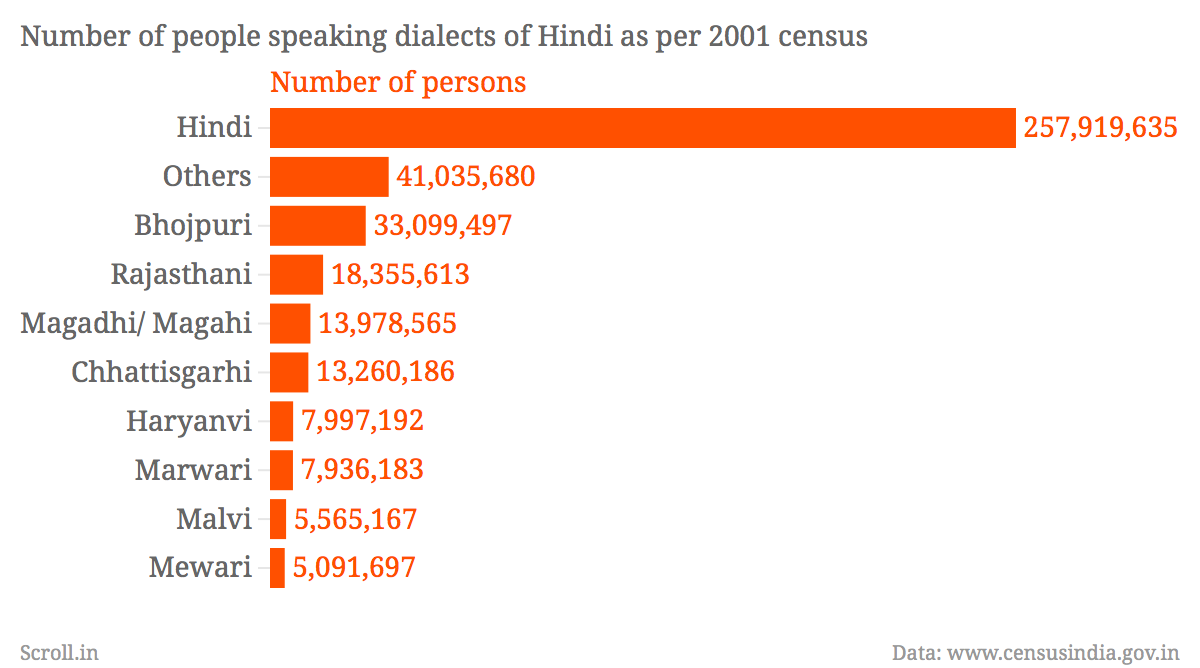

However, the devil is in the details. In reality, only about 26% of Indians in the 2001 census reported that Hindi was their mother tongue. But the census also counts speakers of more than 49 other related linguistic traditions and dialects as Hindi speakers. As a result, people who listed their mother tongues as Bhojpuri, Harayanvi, Maghadi, Marwari, Garhwali and scores of others were also categorised as Hindi speakers.

This has long been a vexed issue. "The question of the status of Hindi in the Indian Census has been debated since the earliest census exercises," said GN Devy, the chairperson of the People's Linguistic Survey of India, which was started in 2010 to create a linguistic portrait of India that is "rooted in people’s perception of language".

Devy said that the problem arose with the official Linguistic Survey of India conducted between 1894 and 1928 under the supervision of British civil servant George Grierson. That survey used the word "dialect" to categorise several languages spoken by smaller groups. Many languages of present-day Uttarakhand, Bihar, Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and Himachal Pradesh were described as dialects, Devy said.

"So long as that misconception is not removed, the exact status of Hindi as a language shall not be known," Devy said.

However, he cautioned against singling out Hindi "as an instance of over-enthusiasm of language imperialism". At one time, Konkani was seen as a dialect of Marathi as well as that of Kannada; Oriya was understood as a sub-set of Bangla, while Kuchhi in Gujarat is perceived as a sister of Gujarati.

Said Devy, "The question of 'language and dialect' has not been properly sorted out in part of the world so far."

Karunanidhi said that the order was an attempt to "impose Hindi against one's wish". He said it should "be seen as an attempt to treat non-Hindi speakers as second class citizens".

However, home minister Rajnath Singh clarified in a tweet, "The Home Ministry is of the view that all Indian languages are important. The Ministry is committed to promote all languages of the country."

On the social media, the directive found several supporters. Some claimed that the order was justified because Hindi is, after all, India's national language. It isn't: it's one of India's two official language, along with English.

Others made a majoritarian argument, suggesting that Hindi should be made the national language because it is the mother tongue of about 45% of all Indians.

That, after all, is what the Census of India says.

However, the devil is in the details. In reality, only about 26% of Indians in the 2001 census reported that Hindi was their mother tongue. But the census also counts speakers of more than 49 other related linguistic traditions and dialects as Hindi speakers. As a result, people who listed their mother tongues as Bhojpuri, Harayanvi, Maghadi, Marwari, Garhwali and scores of others were also categorised as Hindi speakers.

This has long been a vexed issue. "The question of the status of Hindi in the Indian Census has been debated since the earliest census exercises," said GN Devy, the chairperson of the People's Linguistic Survey of India, which was started in 2010 to create a linguistic portrait of India that is "rooted in people’s perception of language".

Devy said that the problem arose with the official Linguistic Survey of India conducted between 1894 and 1928 under the supervision of British civil servant George Grierson. That survey used the word "dialect" to categorise several languages spoken by smaller groups. Many languages of present-day Uttarakhand, Bihar, Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and Himachal Pradesh were described as dialects, Devy said.

"So long as that misconception is not removed, the exact status of Hindi as a language shall not be known," Devy said.

However, he cautioned against singling out Hindi "as an instance of over-enthusiasm of language imperialism". At one time, Konkani was seen as a dialect of Marathi as well as that of Kannada; Oriya was understood as a sub-set of Bangla, while Kuchhi in Gujarat is perceived as a sister of Gujarati.

Said Devy, "The question of 'language and dialect' has not been properly sorted out in part of the world so far."

Limited-time offer: Big stories, small price. Keep independent media alive. Become a Scroll member today!

Our journalism is for everyone. But you can get special privileges by buying an annual Scroll Membership. Sign up today!