"Kejriwal is a bhagauda. He was given a chance to run the government but he ran away."

On trains, in buses, at streets corners and in village gatherings, this was the most commonly heard sentiment about the Aam Aadmi Party and its leader – until the train crossed into the fields of Punjab. The landscape shifted and so did political sentiment.

"Koi chaprasi bhi apna daftar nahi chadhta inhaane CM di kursi chadd di. Even a peon does not give up his job, he gave up the position of the chief minister." Charanjit Singh, an old man in a village near Patiala, who identified himself as a supporter of the Akali Dal, spoke with admiration for Arvind Kejriwal's “sacrifice”.

Sacrifice appeals to the Punjabi psyche, said Satwant Singh, a Left activist, as does Kejriwal’s image as an underdog. "If a small man shows courage and takes on someone tagada, people root for him."

But you don't have to look deep in the Punjabi psyche to understand why AAP is doing well in Punjab.

The state has traditionally swung between the Congress and the Akali Dal-Bharatiya Janata Party combine. In the last assembly elections in 2012, the Akalis sprung a surprise and made history when they bucked anti-incumbency and won a second term. As the joke goes, even the Akalis were surprised that they won.

This time, even if they flooded the villages with terror, alcohol and money, said an old man in Sangrur, there would be no escaping the wrath of voters. But the principal opposition party, the Congress, faces anti-incumbency at the centre too.

This has opened up a foothold for the AAP in Punjab, which, unlike other states, does not have multiple competing parties and has space for a third political formation.

What also seems to be helping AAP is the choice of its candidates. Most of them are people with reputations for being independent and engaged with public life, as Scroll.in found in the Malwa region.

Patiala is the stronghold of the Indian National Congress. Its tallest leader in the state and former chief minister Amarinder Singh belongs to the family that ruled the erstwhile princely state of Patiala. With Singh taking on the BJP’s Arun Jaitley in Amritsar, his wife, Preneet Kaur, a minister in the United Progressive Alliance government, is once again contesting the Lok Sabha elections from Patiala.

Not far from the palatial home of the Maharani, as Kaur is known, is the poor man’s clinic of Dr Dharamvir Gandhi, the AAP’s first time candidate. At Gandhi’s clinic, dalits, brick kiln workers, landless labourers are treated for free. There is a tiered fee structure for the rest: Rs 50 for skilled workers, Rs 100 for professionals, Rs 150 for on-resident Indians.

One morning last week, as his colleagues sat attending patients who had come from afar, 62-year-old Gandhi rushed in and out of his home that serves as his clinic, with just enough time for his wife to thrust an egg sandwich into his hands. From a quiet life as a doctor, what had prompted him to enter the chaotic electoral arena, I asked him, as he jumped into his car, headed for an election meet.

“I have been in politics all along,” said Gandhi, a short, bespectacled man with a thin crop of graying hair. “I courted arrest as a student leader during the Emergency. I spent two-and-a-half years in the slums of Ludhiana among migrant workers. I took part in the farmer’s movement. I have been with people’s struggles all this while. And I run a clean practice as a doctor. There is so much inequality in society you cannot charge people at one level. These days, my fellow doctors get a smart lady to sit at the reception. She charges people Rs 300 and only then are they allowed to enter. By doing this, you are denying science to poor people. Science belongs as much to slums as to South Delhi and South Bombay. It is the heritage of all mankind.”

What were the issues on which he was seeking a mandate, I asked.

“Punjab is witnessing tyranny. Sukhbir Badal is out to grab Punjab through his gangmen. They have turned the state into mafia raj. There is drug mafia, transport mafia, sand mafia, cable TV mafia…"

The charges against the Badals are indeed serious, as various media investigations have shown.

“Whether it is coal and oil in the country, or buses, sand, gravel, cable TV in Punjab…inha Badala ne, maharajiya ne, ambaniya ne kabza kar littaa hai. These Badals, Maharajas and Ambanis have captured it all,” Gandhi thundered into a microphone at a roadside gathering ten km outside Patiala.

Before I took his leave, I had one last question.

Gandhi was a name more commonly found in Gujarat. What was a Gandhi doing in Punjab?

“I got the name Gandhi for my work as a student activist. My father was an adarshwadi teacher. He did not believe in religion and caste. He did not want his sons to associate with any narrow identity. He named my brothers Harvir Kabir and Yashvir Nanak. And he named me Dharamvir Bulla…Bulla, as in Bulleh Shah, the revolutionary rebel poet. Have you heard of him?”

With this, he broke into a couplet by Bulleh Shah:

Bulleh nalu chulha changa/Jispe ann pakayeeda

Thakur nalu theekar changa/Pulpul dana khayeeda

Pauthi nalu khuthi changi/Jiske rizak kamaeeda

Bulleh Shah nu murshid milaya/Darshan ho gaya sai da

The stove is better than Bulla/You can cook on it

The earthen pot is better than God/You can serve in it

The donkey is better than the scripture/You can earn a living with it

Bulleh Shah has found a teacher and glimpsed God

***

“Mann Sahab, I love you,” said a young boy, coming up to the window of the SUV in which Bhagwant Mann drove across Sangrur. A stand-up comedian famous for political satire, Mann is a celebrity in Punjab. He is contesting on an AAP ticket from Sangrur.

So strong are his chances of winning that his political opponents have taken the trouble of finding an unknown farmer named Bhagwant Singh in the constituency and getting him to file a nomination as an independent with the symbol of a kite. As The Tribune reported, “Some voters intending to vote for Bhagwant Mann may end up voting for Bhagwant Singh (by mistake) as 'kite' was his election symbol in the 2012 Assembly elections.”

In 2012, Mann had contested his first election, finishing third in Lehragaga constituency with a vote share of 21.8%. He had contested on the kite symbol as a candidate of the Punjab People’s Party. The PPP was created in 2011 by Manpreet Badal, the cousin of Sukhbir Badal, who had rebelled against the Akali Dal. The party did not win any seats and Manpreet is now contesting the Lok Sabha elections on a Congress ticket.

“Bhagat Singh did not get along with the Congress. How can his followers join it now?” says Mann, explaining why he ended his association with Manpreet Badal, choosing to join AAP instead.

Mann’s friendship with Arvind Kejriwal dates back to the Anna Hazare agitation in 2011, which he had attended at Delhi’s Ramlila Grounds along with 400 men dressed in Bhagat Singh-style basanti pagadis, yellow coloured turbans. “We had gone to mark Bhagat Singh’s attendance,” he said.

Dressed in jeans and a white short kurta, styled as a modern-day protégé of Bhagat Singh, Mann has a strong appeal among young people, evident from the number of young men riding motorcycles and racing ahead of his car from village to village.

“Politicians might get happy at a sight like this but mere liye dukh ki baat hai. Why are these young men here on a working day? Why are they not at work? What would they gain by joining my election campaign? Kya inhone mere se MLA ki ticket leni hai? Clearly not. They are joining because they hope for a day when the youth of Punjab will not have to queue up outside embassies for visas because there would be enough jobs in the state itself.”

At a village gathering, Mann spends much time addressing the women, who laugh at all his jokes.

“Badal sahab loves to get his pictures clicked,” he told them. “Paani di tanki te badal ki photo. Cycle ki tokeri pe badal di photo. From water tanks to bicycle baskets, BPL cards to ambulances, you’ll find Badal’s picture on them. Now, we have come to know the government plans to distribute utensils among the poor. Pitalla te bhi bebe badal ki photo hai. Even the utensils, let me tell you sisters, have Badal’s photo…”

The women laughed. And then, Mann delivered the punchline. “What Badal does not know is that this time the women of Punjab would wipe his party clean.”

The jokes aside, Mann’s political astuteness is evident from the way he gets a Sikh farmer from Gujarat to brief villagers about how Sikh settlers in Kutch had to fight eviction notices by Narendra Modi’s government. “These are the kind of anti-Punjabi people the Badals are in alliance with,” Mann told the gathering. The party has nominated Himmat Singh Gill, the lawyer fighting the case of Sikh farmers in Gujarat, as its candidate from Anandpur Sahib constituency.

Isn’t politics more difficult than comedy, I asked him.

“Comedy is a very serious business. It is easier to make people weep than laugh. They are anyway on the brink of tears thanks to inflation, unemployment, cancer…”

He is a consummate entertainer but what had he done at the grassroots to be taken seriously as a politician, I asked.

“I was born in a village. I grew up in a village. Mere se zyada ground kaun janta hai,” he said. “Baaki inhone tamasha banaya hai mulk ka. It is the politicians who have made a tamasha of the country. They go around attacking each other with pepper spray in Parliament. As for Sukhbir Badal, he is the real comedy king of Punjab. Do you know what he said? Punjab ki sadak aisi bana donga ek haath mein peg pakado ek mein steering aur peg girega nahi. I would make the roads of Punjab so smooth that you can hold the steering wheel in one hand and your drink in the other and it won’t spill.”

Did Badal indeed say this or was this AAP hyperbole?

Last October, the Hindustan Times reported that while distributing bicycles among school girls, Badal “went overboard with claims about road development in Punjab. He said the highways and traffic would be so good that 'je daaru pee ke vi drive karoge tan accidents nahi honge (even if you drink and drive, there will be no accident).' Punjab is number two in the country in road-accident deaths, and drunk driving is one of the main reasons.”

***

Dilli takhat te daler nu bhejji, Hakka de layi sher no bheji. Send a brave man to the seat in Delhi. Send the lion who can fight for your rights.

The soft-spoken Harvinder Singh Phoolka makes for an unlikely sher.

The man on the street in Ludhiana calls the senior lawyer who practices at the Supreme Court Phoolka Sahab and tells you that he fought for the victims of the 1984 anti-Sikh riots for free.

If you ask whether, as the candidate of AAP, Phoolka Sahab stands a chance to win the election, you would be told, “Tagada muqabala hai. It is a close contest.”

Phoolka is pitted against the Congress’s Ravneet Singh Bittu, the grandson of Beant Singh, the former Congress chief minister slain by militants, Akali Dal’s Manpreet Singh Ayali and independent candidate Simarjit Singh Bains.

If the Akalis and Congress have organisational strength, Bains is seen as the tough guy jo gareeba de kam karaunda hai (who gets poor people’s work done). “He runs a service centre where you can go and seek help for anything, from licences to police cases,” a tea-shop vendor told me.

“We are trying to educate voters that this is not an election of a councillor who will get your ration cards made,” Phoolka said when I met him in the AAP’s office. “You need to send a person who can represent you in the Parliament and work towards changing the system so that you do not need not go to politician to get your work done…Leaders have paralysed the administrative system. They have captured all power. We need to restore the administrative system. We need to implement the laws and get people the rights that laws give them.”

But this legalistic view of politics might not win votes among an electorate accustomed to a politics of patronage. A woman showed at AAP’s office to request Phoolka to get her son admitted to high school without fees. Phoolka explained that he could not help her until the elections were over. “Come back later and we will evaluate your case,” he told her. “I am associated with several educational institutions that give scholarships to needy students,” he told me.

What appeals much more to voters in Ludhiana is Phoolka’s record of fighting the 1984 cases. This goes well with the larger attempt by the AAP to claim credit for demanding that a special investigation team be set up to probe the 1984 cases afresh. Justice, rights, struggle are the words resonated the most in the slogans of the AAP workers as Phoolka’s roadshow wound through the traffic-snarls near Ludhiana railway station, the dense markets, low-income neighbourhoods and dalit colonies, with Rakhi Birla, the AAP leader from Delhi, as the star attraction.

“Sadda haq, Aithe Rakh.”

“Bahar Niklo Dukano se, Jung Lado Baimaano Se.”

“Pehle Sheela Haari hai, ab Badal ki baari hai.”

The best slogan, however, sprung up spontaneously in a dalit colony, where women stood outside their homes, greatly enthused by the presence of Rakhi Birla. “After all, she is from our community,” they told me, before they broke into, “Aam Aadmi Party ki balle balle, baaki saare thalle thalle.”

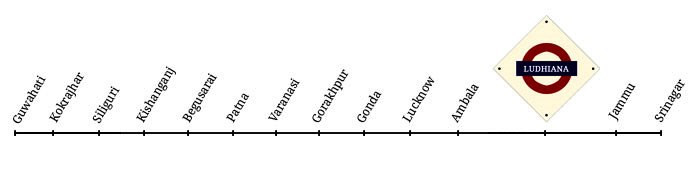

Click here to read all the stories Supriya Sharma has filed about her 2,500-km rail journey from Guwahati to Jammu to listen to India's conversations about the elections – and life.

Limited-time offer: Big stories, small price. Keep independent media alive. Become a Scroll member today!

Our journalism is for everyone. But you can get special privileges by buying an annual Scroll Membership. Sign up today!