The stalls on Dongtai Lu, Shanghai's antique market street, are packed with vintage curios, memorabilia of Chairman Mao and postcards of Old Shanghai. When I visited, the vendors waved Old Shanghai antiques at me, sensing that I was interested in the time when the city was the Far East's hotspot dominated by Westerners, thanks to the unequal Opium war treaties of the mid-1800s.

But I was looking for something rather specific: photographs that would help me piece together the forgotten lives of the Sikhs who lived in Shanghai for over half a century, starting from 1884.

I’ve been fascinated by Sikhs in Shanghai since 2010, when as an expatriate in that city I found a picture in a local guidebook mentioning a Sikh gurudwara as a relic of the Old Shanghai days.

Shanghai has a tumultuous past. The treaty-port was split into foreign enclaves, each with their own judicial, economic and political laws and postal systems. Chinese residents lived in the walled portions of the city in grimy conditions. The International Settlement, a British zone with American leavening, was governed by Shanghai Municipal Council, an administrative body consisting of officials elected by taxpayers. The SMC also supervised the security of the International Settlement through the Shanghai Municipal Police.

Since 1884, the Shanghai Municipal Police began recruiting Sikh men from British India to man the chaotic traffic intersections. Attired in khakis in summers and heavy, dark coats in winter, the Sikhs never failed to attract attention. Their imposing frame, bushy beards and red turbans added the picturesque element to the very international port city of Shanghai.

In addition to finding employment as policemen, Sikhs worked as watchmen, earning money on the side as moneylenders. Indian Sikhs were also recruited for the British police force in Tientsin (Tianjin), Amoy (Xiamen) and Hankow (Hankou, Wuhan).

In the stalls of the Dongtai Lu vendors, I had to sift through stacks of photo postcards to find ones with Sikh policemen. In the eyes of Chinese, the Sikh policeman represents the humiliating British imperialism and thus earned the very derogatory sobriquet of Hong-Tou-A-san – turbaned number three, referring to their lowly placement in the social hierarchy of that era.

Unfortunately, for the very smartly bedecked Sikh policeman in Shanghai and elsewhere in China, their narratives are extremely blurred. The Sikh policeman who was a symbolic prop for the pompous British Empire in several of their colonies has remained very much in the periphery of historical chronicles and records. The dilapidated gurudwara, more than a century old, is the only testimony to their presence here.

During that time, Shanghai’s Sikhs were enthusiastic supporters of the Ghadr Party’s fight of Indian freedom, as also for Subhas Chandra Bose’s Indian National Army.

Sikhs weren’t the only Indians in Old Shanghai. Parsi opium traders also made lucrative profits there. However, the stories of Dr Cavas Lalkaka, who was shot accidentally in 1909 in London by freedom fighter Madan Lal Dingra, and the journeys of photojournalist Sam Tata aren’t as well known as the exploits of Jamshetji Jejeebhoy, the Readymoneys and the Wadias, who used the profits of their opium trading in China to fund infrastructure in Mumbai. In fact, Shanghai once had a Parsi agiary. Shanghai was also home to Punjabi Muslims, Ismaili Merchants, Gurkhas and Sindhis, who were also frequently misclassified as Sikhs.

Yet, a few incidents catapulted Shanghai Indians to fame, providing us with a tantalising peek of what lay beneath the dull and sketchy official accounts. After all, it was Old Shanghai, the Paris of the East and city of sin.

One Shanghai Sikh who attained notoriety was Atma Singh, a policeman who brutally murdered another Sikh in 1936 for insulting his wife. He was sentenced to death. Most versions of Atma Singh’s story recall that the rope being used to hang him broke as he was on the gallows. He made headlines around the world for surviving the bungled hanging and was revered as a holy man by his compatriots, who considered it a miracle. Eventually, his sentence was commuted to life imprisonment.

In early 1940s, the Shanghai scene was enlivened by the presence of Princess Sumaire of Patiala, a cousin of painter Amrita Sher-gill and scam artist to boot. A bigamist with a flair for losing money, she hopped around in various (and at times) dubious social circles flaunting her wealth and fashion sense. She was also labelled a nymphomaniac and lesbian by a British police official investigating her antecedents. A collaborationist under Japanese occupied Shanghai, she married a Japanese-American without divorcing her first husband in India.

By 1949, most Indians left Communist China, heading either homeward, Hong Kong or to greener shores in the West. With their departure, only the pale footprints of their China sojourn remains. It is my hope that I can excavate the archives for the very interesting, still unexplored tales of Old Shanghai Indians.

Meena Vathyam displays her latest discoveries on her Sikhs in Shanghai blog. Follow her work on Facebook here.

But I was looking for something rather specific: photographs that would help me piece together the forgotten lives of the Sikhs who lived in Shanghai for over half a century, starting from 1884.

I’ve been fascinated by Sikhs in Shanghai since 2010, when as an expatriate in that city I found a picture in a local guidebook mentioning a Sikh gurudwara as a relic of the Old Shanghai days.

Shanghai has a tumultuous past. The treaty-port was split into foreign enclaves, each with their own judicial, economic and political laws and postal systems. Chinese residents lived in the walled portions of the city in grimy conditions. The International Settlement, a British zone with American leavening, was governed by Shanghai Municipal Council, an administrative body consisting of officials elected by taxpayers. The SMC also supervised the security of the International Settlement through the Shanghai Municipal Police.

Since 1884, the Shanghai Municipal Police began recruiting Sikh men from British India to man the chaotic traffic intersections. Attired in khakis in summers and heavy, dark coats in winter, the Sikhs never failed to attract attention. Their imposing frame, bushy beards and red turbans added the picturesque element to the very international port city of Shanghai.

In addition to finding employment as policemen, Sikhs worked as watchmen, earning money on the side as moneylenders. Indian Sikhs were also recruited for the British police force in Tientsin (Tianjin), Amoy (Xiamen) and Hankow (Hankou, Wuhan).

In the stalls of the Dongtai Lu vendors, I had to sift through stacks of photo postcards to find ones with Sikh policemen. In the eyes of Chinese, the Sikh policeman represents the humiliating British imperialism and thus earned the very derogatory sobriquet of Hong-Tou-A-san – turbaned number three, referring to their lowly placement in the social hierarchy of that era.

Unfortunately, for the very smartly bedecked Sikh policeman in Shanghai and elsewhere in China, their narratives are extremely blurred. The Sikh policeman who was a symbolic prop for the pompous British Empire in several of their colonies has remained very much in the periphery of historical chronicles and records. The dilapidated gurudwara, more than a century old, is the only testimony to their presence here.

Shanghai gurudwara, 1908, Denniston & Sullivan.

During that time, Shanghai’s Sikhs were enthusiastic supporters of the Ghadr Party’s fight of Indian freedom, as also for Subhas Chandra Bose’s Indian National Army.

Sikhs weren’t the only Indians in Old Shanghai. Parsi opium traders also made lucrative profits there. However, the stories of Dr Cavas Lalkaka, who was shot accidentally in 1909 in London by freedom fighter Madan Lal Dingra, and the journeys of photojournalist Sam Tata aren’t as well known as the exploits of Jamshetji Jejeebhoy, the Readymoneys and the Wadias, who used the profits of their opium trading in China to fund infrastructure in Mumbai. In fact, Shanghai once had a Parsi agiary. Shanghai was also home to Punjabi Muslims, Ismaili Merchants, Gurkhas and Sindhis, who were also frequently misclassified as Sikhs.

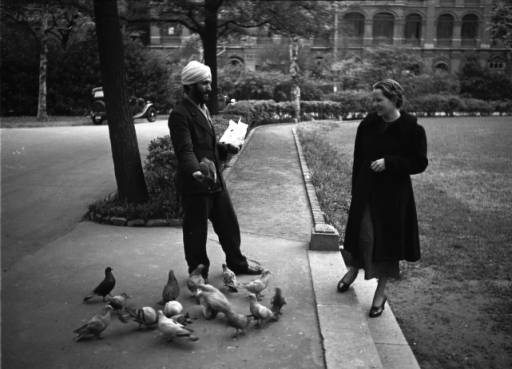

Sikh man and unknown woman, 1937.

Yet, a few incidents catapulted Shanghai Indians to fame, providing us with a tantalising peek of what lay beneath the dull and sketchy official accounts. After all, it was Old Shanghai, the Paris of the East and city of sin.

One Shanghai Sikh who attained notoriety was Atma Singh, a policeman who brutally murdered another Sikh in 1936 for insulting his wife. He was sentenced to death. Most versions of Atma Singh’s story recall that the rope being used to hang him broke as he was on the gallows. He made headlines around the world for surviving the bungled hanging and was revered as a holy man by his compatriots, who considered it a miracle. Eventually, his sentence was commuted to life imprisonment.

In early 1940s, the Shanghai scene was enlivened by the presence of Princess Sumaire of Patiala, a cousin of painter Amrita Sher-gill and scam artist to boot. A bigamist with a flair for losing money, she hopped around in various (and at times) dubious social circles flaunting her wealth and fashion sense. She was also labelled a nymphomaniac and lesbian by a British police official investigating her antecedents. A collaborationist under Japanese occupied Shanghai, she married a Japanese-American without divorcing her first husband in India.

By 1949, most Indians left Communist China, heading either homeward, Hong Kong or to greener shores in the West. With their departure, only the pale footprints of their China sojourn remains. It is my hope that I can excavate the archives for the very interesting, still unexplored tales of Old Shanghai Indians.

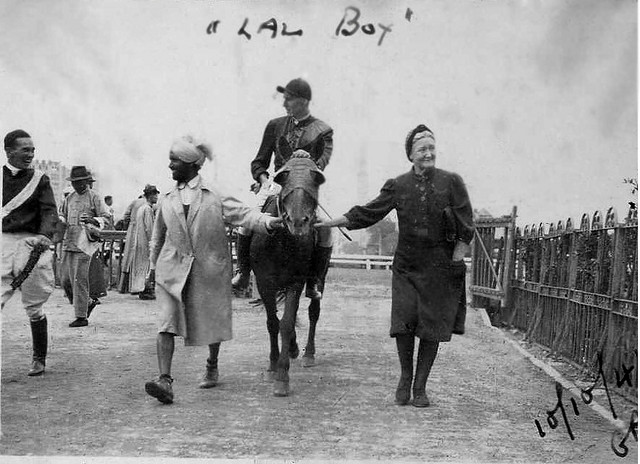

Shanghai Race Course, 1944.

Hockey team.

Traffic policeman.

Meena Vathyam displays her latest discoveries on her Sikhs in Shanghai blog. Follow her work on Facebook here.

Scroll has produced award-winning journalism despite violent threats, falling ad revenues and rising costs. Support our work. Become a member today.

In these volatile times, Scroll remains steadfastly courageous, nuanced and comprehensive. Become a Scroll Member and support our award-winning reportage, commentary and culture writing.