Earlier this week the West Bengal secretariat of the Communist Party of India (Marxist), which leads the Opposition Left Front alliance in the state, expelled Abdur Razzak Molla, an eight-time legislator, for anti-party activities.

Trouble had been brewing for months. Molla, who represents the Canning East assembly constituency in South 24 Parganas district, bordering Kolkata on the south, had openly criticised top party leaders for their style of functioning and their earlier policies relating to land acquisition and industrialisation.

"I have been speaking up internally for a long time," Molla told Scroll.in over the phone. "But no one addressed my concerns, so I became frustrated and had to go public. I welcome the expulsion. I am now ready to float a party of the working class. The current leadership has no knowledge of class struggle, whether rural or urban."

In what was probably the strongest recent expression of his discontent, Molla announced last week that he would launch a new organisation called the Social Justice Forum as an umbrella for several Muslim and Dalit groups. Molla, who was the land reforms minister in the CPI-M-led Left Front government that was voted out of power in 2011, said that his political party would work towards contesting the 2016 assembly election.

Mohammed Salim, a spokesman for the CPI-M, declined to comment when asked whether the party felt there was any merit in the issues Molla was raising. "I would not like to engage in a dialogue over this issue," he said over the phone. "We have other priorities at hand."

Molla has been criticising the leadership since the party's stunning defeat in the 2011 assembly election, in which he was one of the few ministers to have won a seat. He has, in particular, said that the top leaders, including the former chief minister Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee, who lost his seat from Jadavpur, ought to have taken responsibility for the debacle.

The loss, he said, was a direct consequence of the Left Front government's anti-poor industrialisation and land acquisition policies, such as in Singur. The party needs to be more sensitive to caste issues, and usher in greater representation for Muslims and Dalits, he said.

Molla isn't the only one who is disillusioned. "Razzak Molla may not pose a serious electoral threat but the issues that he has been raising can't be brushed aside," said Prasenjit Bose, the former Delhi-based head of the CPI-M's research unit, who quit the party in 2012 after it supported the Congress's presidential candidate Pranab Mukherjee. "The CPI-M has become disconnected from the poor."

Once considered close to the party's general secretary, Prakash Karat, Bose, like Molla, had been unhappy on several other counts, such as the party's actions in Singur and Nandigram, and its failure to rectify those mistakes with any seriousness.

Molla's departure comes at a time when the CPI-M is at its lowest ebb nationally and in West Bengal, its stronghold. Despite this, the party certainly cannot be written off yet: its annual rally at the Brigade Parade grounds in Kolkata in February attracted an estimated half a million supporters, probably a larger turnout that the one at the ruling Trinamool Congress rally in January. However, that won't change its bleak prospects in the national election later this year, say political commentators

For the general election, its performance in West Bengal will be crucial. The party has a meaningful presence in only two other states: Kerala and Tripura. Of the party's 16 Lok Sabha seats, nine are from West Bengal. Kerala accounts for four, Tripura for two and Tamil Nadu for one.

It is too early to say how much momentum Molla's party can gain over the next few years, but the composition of Bengal's population is certainly in his favour. Muslims, Dalits, scheduled castes and scheduled tribes together constitute 54 percent of the state's population.

Minorities have historically been an important support base for the CPI-M, but many shifted to the Trinamool Congress in the 2009 general election and the 2011 assembly election. "The party could see a further erosion of support from Muslims in this general election," said Jibananda Bose, the publisher and news coordinator of the Kolkata-based Bartaman Patrika, the Bengali newspaper with the second-largest readership.

"Even though Mamata Banerjee's Trinamool Congress government in Bengal has made a mess of administration, she is getting away with it because the Left is so scattered," said Ajoy Bose, a Delhi-based political commentator. Added Prasenjit Bose: "Every government makes errors, but only an effective Opposition can capitalise on them."

Asked what the CPI-M felt about its prospects in the general election, its spokesman, Mohammed Salim, said, "Please consult our updated party programme."

The CPI-M's prospects in the near future are dire because it has faced a string of massive election losses yet has shown no obvious sign of having conducted a thorough postmortem, let alone acting on those findings, say political commentators. Had it done so, its leaders may have dealt with Molla and other dissidents more productively.

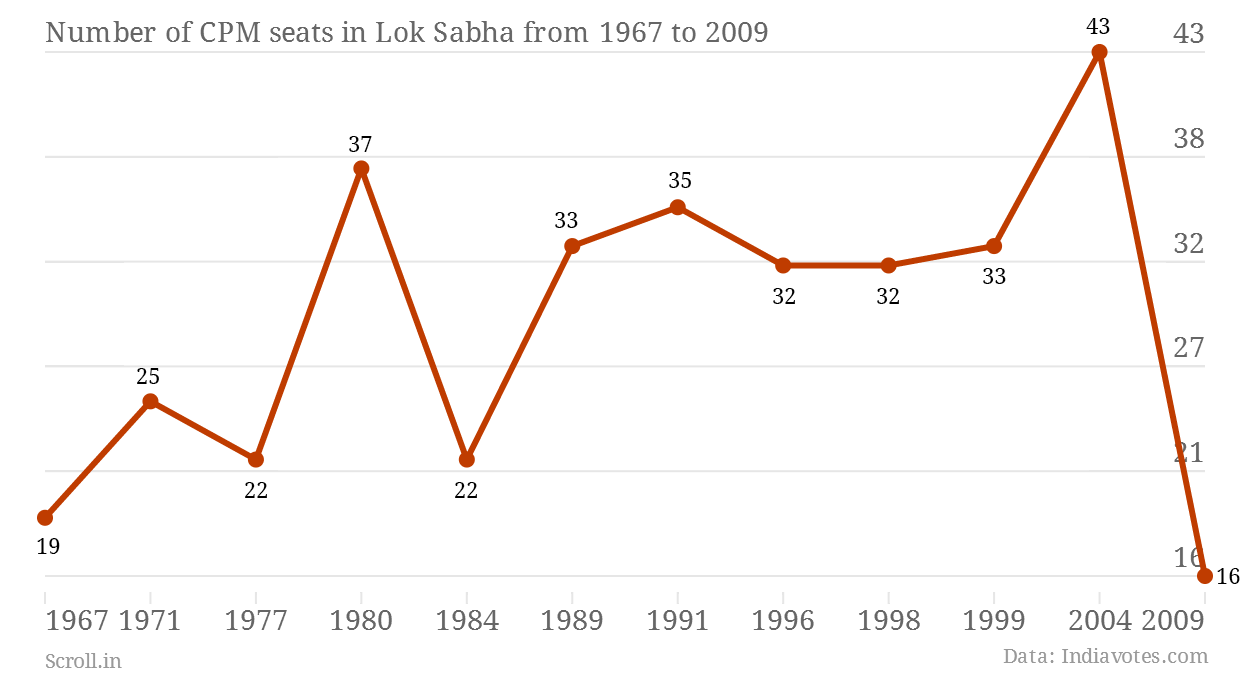

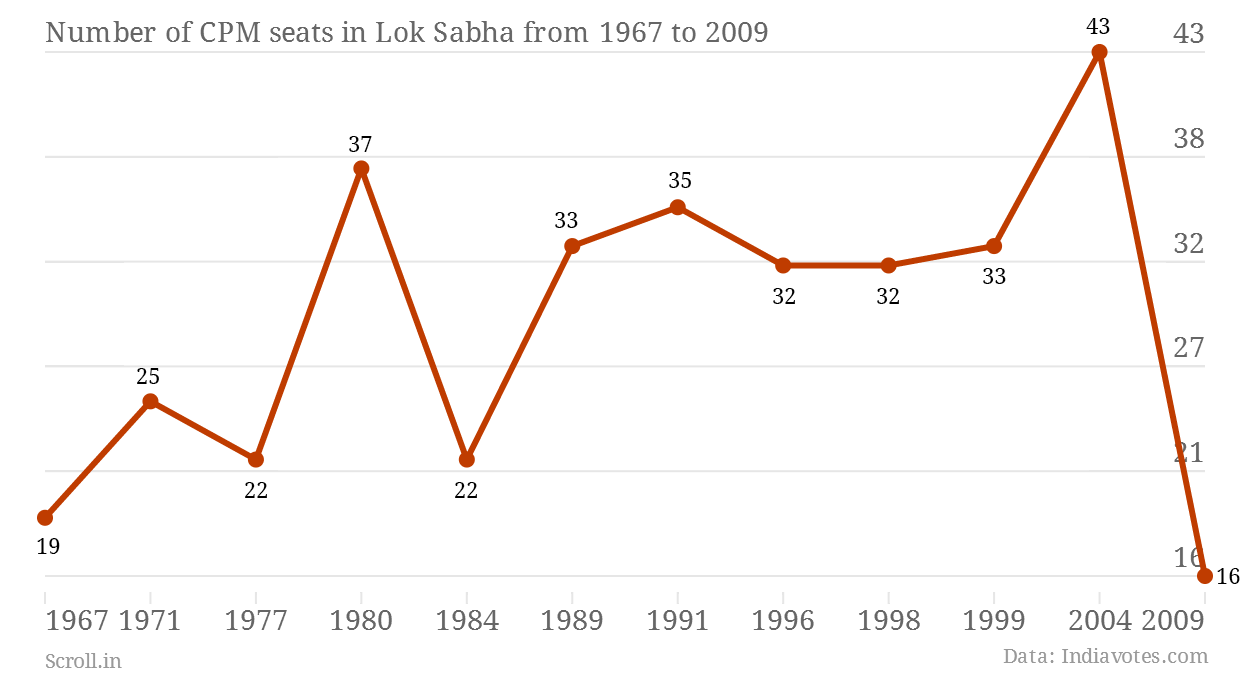

In the 2009 national election, the party's seat tally plunged to 16 from 43 and its vote share also fell close to its lowest level.

In 2011, it fared even worse in the West Bengal election, with its seat tally plummeting to 40 from 176 and its vote share falling to its lowest level, after being in power for 34 years in a row. The fortunes of the Left Front, which includes two smaller parties, was only a shade better.

Then, in 2013, in panchayat elections across West Bengal that were seen as a warm-up to this year's general election, the CPI-M won in just one of 17 districts, while the Trinamool Congress swept to a victory in 13.

Yet, the party does not seem to have held anyone accountable for these losses, say commentators. "There was a huge debacle in the poll, but how many heads at the top have rolled?" asked Prasenjit Bose.

The party has no credible second tier of leadership and does not brook any discussion or dissent, said its critics. "It is a very Stalinist party," said Monobina Gupta, author of Left Politics in Bengal: Time Travels among Bhadralok Marxists, which among other things chronicles her own engagement and subsequent disillusionment with the party. "You will not get tickets if you do not support the views of the dominant leaders."

Because of this, it is not equipped to react to the country's changing political situation, especially with the entry of the Aam Aadmi Party. "Politics is working out very differently in India," Gupta said. "You may not agree with everything the AAP is doing, but it is a radical phenomenon. Also, social movements that work outside political structures are growing in importance – they may be small but they are very strong. The inability to see all of this and to speak the same language shows they [the leaders of the CPI-M] have forgotten the kind of politics they themselves once practised in the '60s, outside existing paradigms."

Besides stagnation at the top, of leadership, or perhaps because of this, the party also faces problems at the grassroots. Some of the lower-rung cadres have joined the Trinamool Congress, and there are hardly any recruits, said several political commentators.

Although this is partly the fate of most parties that are out of power, the CPI-M has not done much to revitalise the cadres. "If you want to participate in parliamentary democracy, which the CPI-M does, then you are mandated to go in to states with the poorest of the poor," Gupta said. "But they haven't moved and all those spaces have gone to" the Samajwadi Party, the Bahujan Samaj Party and even to the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Samiti.

Trouble had been brewing for months. Molla, who represents the Canning East assembly constituency in South 24 Parganas district, bordering Kolkata on the south, had openly criticised top party leaders for their style of functioning and their earlier policies relating to land acquisition and industrialisation.

"I have been speaking up internally for a long time," Molla told Scroll.in over the phone. "But no one addressed my concerns, so I became frustrated and had to go public. I welcome the expulsion. I am now ready to float a party of the working class. The current leadership has no knowledge of class struggle, whether rural or urban."

In what was probably the strongest recent expression of his discontent, Molla announced last week that he would launch a new organisation called the Social Justice Forum as an umbrella for several Muslim and Dalit groups. Molla, who was the land reforms minister in the CPI-M-led Left Front government that was voted out of power in 2011, said that his political party would work towards contesting the 2016 assembly election.

Mohammed Salim, a spokesman for the CPI-M, declined to comment when asked whether the party felt there was any merit in the issues Molla was raising. "I would not like to engage in a dialogue over this issue," he said over the phone. "We have other priorities at hand."

Molla has been criticising the leadership since the party's stunning defeat in the 2011 assembly election, in which he was one of the few ministers to have won a seat. He has, in particular, said that the top leaders, including the former chief minister Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee, who lost his seat from Jadavpur, ought to have taken responsibility for the debacle.

The loss, he said, was a direct consequence of the Left Front government's anti-poor industrialisation and land acquisition policies, such as in Singur. The party needs to be more sensitive to caste issues, and usher in greater representation for Muslims and Dalits, he said.

Molla isn't the only one who is disillusioned. "Razzak Molla may not pose a serious electoral threat but the issues that he has been raising can't be brushed aside," said Prasenjit Bose, the former Delhi-based head of the CPI-M's research unit, who quit the party in 2012 after it supported the Congress's presidential candidate Pranab Mukherjee. "The CPI-M has become disconnected from the poor."

Once considered close to the party's general secretary, Prakash Karat, Bose, like Molla, had been unhappy on several other counts, such as the party's actions in Singur and Nandigram, and its failure to rectify those mistakes with any seriousness.

Molla's departure comes at a time when the CPI-M is at its lowest ebb nationally and in West Bengal, its stronghold. Despite this, the party certainly cannot be written off yet: its annual rally at the Brigade Parade grounds in Kolkata in February attracted an estimated half a million supporters, probably a larger turnout that the one at the ruling Trinamool Congress rally in January. However, that won't change its bleak prospects in the national election later this year, say political commentators

For the general election, its performance in West Bengal will be crucial. The party has a meaningful presence in only two other states: Kerala and Tripura. Of the party's 16 Lok Sabha seats, nine are from West Bengal. Kerala accounts for four, Tripura for two and Tamil Nadu for one.

It is too early to say how much momentum Molla's party can gain over the next few years, but the composition of Bengal's population is certainly in his favour. Muslims, Dalits, scheduled castes and scheduled tribes together constitute 54 percent of the state's population.

Minorities have historically been an important support base for the CPI-M, but many shifted to the Trinamool Congress in the 2009 general election and the 2011 assembly election. "The party could see a further erosion of support from Muslims in this general election," said Jibananda Bose, the publisher and news coordinator of the Kolkata-based Bartaman Patrika, the Bengali newspaper with the second-largest readership.

"Even though Mamata Banerjee's Trinamool Congress government in Bengal has made a mess of administration, she is getting away with it because the Left is so scattered," said Ajoy Bose, a Delhi-based political commentator. Added Prasenjit Bose: "Every government makes errors, but only an effective Opposition can capitalise on them."

Asked what the CPI-M felt about its prospects in the general election, its spokesman, Mohammed Salim, said, "Please consult our updated party programme."

The CPI-M's prospects in the near future are dire because it has faced a string of massive election losses yet has shown no obvious sign of having conducted a thorough postmortem, let alone acting on those findings, say political commentators. Had it done so, its leaders may have dealt with Molla and other dissidents more productively.

In the 2009 national election, the party's seat tally plunged to 16 from 43 and its vote share also fell close to its lowest level.

In 2011, it fared even worse in the West Bengal election, with its seat tally plummeting to 40 from 176 and its vote share falling to its lowest level, after being in power for 34 years in a row. The fortunes of the Left Front, which includes two smaller parties, was only a shade better.

Then, in 2013, in panchayat elections across West Bengal that were seen as a warm-up to this year's general election, the CPI-M won in just one of 17 districts, while the Trinamool Congress swept to a victory in 13.

Yet, the party does not seem to have held anyone accountable for these losses, say commentators. "There was a huge debacle in the poll, but how many heads at the top have rolled?" asked Prasenjit Bose.

The party has no credible second tier of leadership and does not brook any discussion or dissent, said its critics. "It is a very Stalinist party," said Monobina Gupta, author of Left Politics in Bengal: Time Travels among Bhadralok Marxists, which among other things chronicles her own engagement and subsequent disillusionment with the party. "You will not get tickets if you do not support the views of the dominant leaders."

Because of this, it is not equipped to react to the country's changing political situation, especially with the entry of the Aam Aadmi Party. "Politics is working out very differently in India," Gupta said. "You may not agree with everything the AAP is doing, but it is a radical phenomenon. Also, social movements that work outside political structures are growing in importance – they may be small but they are very strong. The inability to see all of this and to speak the same language shows they [the leaders of the CPI-M] have forgotten the kind of politics they themselves once practised in the '60s, outside existing paradigms."

Besides stagnation at the top, of leadership, or perhaps because of this, the party also faces problems at the grassroots. Some of the lower-rung cadres have joined the Trinamool Congress, and there are hardly any recruits, said several political commentators.

Although this is partly the fate of most parties that are out of power, the CPI-M has not done much to revitalise the cadres. "If you want to participate in parliamentary democracy, which the CPI-M does, then you are mandated to go in to states with the poorest of the poor," Gupta said. "But they haven't moved and all those spaces have gone to" the Samajwadi Party, the Bahujan Samaj Party and even to the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Samiti.

Limited-time offer: Big stories, small price. Keep independent media alive. Become a Scroll member today!

Our journalism is for everyone. But you can get special privileges by buying an annual Scroll Membership. Sign up today!