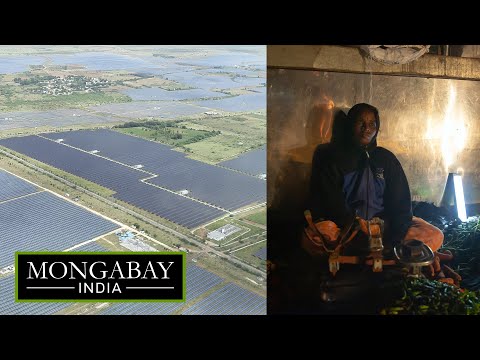

For generations, farmers of Pavagada taluk in Karnataka’s Tumakuru district have gazed at the sky expecting rains to change their fortunes. Declared drought-hit 54 times in the last six decades, some villagers say that installation of a solar park signified a rare occasion when the sun’s harsh rays worked in their favour.

The solar park Shakti Sthala, built on 13,000 acres of land taken on lease from farmers at Rs 21,000 per acre for the first five years, with a five per cent increase every two years, leverages the high average solar radiation of 5.35-kilowatt hour per square metre per day that falls on Pavagada.

Large colourful houses that dot these villages tell us that the park has bettered many lives here. Rich farmers with large landholdings are the true beneficiaries as they retained portions of their land for agriculture while the rest fetched them a good annual lease. Some of the poor farmers with small parcels of land who are now employed as daily-wage labourers in the park have also built big houses.

Approaching the Nagalamadike Hobli (a village cluster where the solar park has come up) from the Pavagada town, it is hard to miss the sales of bikes or plot-for-sale signages by the highway or “international school” buses in canary yellow carrying children from these villages. Most of the homes in Pavagada have more than one two-wheeler. Mahesh, an organic farmer told Mongabay-India that many farmers have bought land in other villages or the town and enrolled their children in the town’s English-medium schools.

“It looked like a win-win situation for both parties,” said Pinaki Halder, National Director of Programmes-India, Landesa, a nonprofit working on land rights. He said, recollecting his conversations with villagers, very few dissenting voices were heard from farmers who were unhappy with the poor quality jobs being offered to them. He believes it has been a positive social change and the youth can focus on formal education now.

On closer examination, however, some of the rich landholders are found to have turned into moneylenders for the poor farmers. Linganna (52) works on Rs 400 daily wage at the solar park. His son, a security guard at one of the solar companies, draws a salary of Rs 14,500.

Linganna took a loan of Rs 10 lakh from a moneylender at an interest of Rs 2 per Rs 100 (in addition to the money he received as compensation for the land he sold for the park) to build a large two-storeyed house, at Rs. 30 lakh (Rs. three million). Farmers like Linganna are pressured to build big houses because most of his peers have built one; jobs at the park have given them the assurance to take loans.

Drawing parallels to the fossil fuel sector, researcher Priya Pillai, who works on the socio-ecological impact of various energy systems, said the renewable energy sector had “disturbing similarities” with the mining industry during the transition phase. “When people get large compensations, they do not spend them wisely,” she said. “They often move into smaller plots and build large houses. They need fuel for their new vehicles and maintain large houses but have no livelihood options. So they keep drawing money from the compensation.”

This highlights the need to include economic empowerment of local communities as a key component while ensuring procedural justice during transitions.

‘Inherently good’ assumption

“One of the biggest challenges of renewable energy growth in India is the assumption that it is inherently good,” said Saksham Nijhawan, Manager, Responsible Energy Initiatives, Forum for the Future, an international sustainability organisation. The draft notification on the Environment Impact Assessment 2020 exempts solar parks from environmental clearance. Large solar parks, however, are bound to impact the environment.

A study titled “Renewable Energy to Responsible Energy: A Call to Action”, done by Forum for the Future with six other organisations, points to a large amount of water needed for periodic cleaning of solar panels. The study says that estimates range between 7,000 litres to 20,000 litres per megawatt per wash. Since approximately 56% of all solar installations are located in arid and semi-arid areas of India (such as Gujarat and Rajasthan), this brings significant risk to the local ecosystem and communities, the study adds.

In Pavagada, many companies have switched to mechanised cleaning in a bid to conserve water. This, however, is leading to job losses; panel-washing is one of the few jobs allocated to locals. An employee of Fortum, a Finland-based solar company at Pavagada, said on conditions of anonymity, that it was a dilemma the company was facing.

Farmers said that during the construction of the park, pollinators like bees and butterflies had disappeared, affecting farm yields. “The PPM level in the area had increased that prevented pollinators’ entry,” Mahesh said. “They returned when the construction stopped but I got very low yield for two years.”

He said large mammals like bears, leopards and jackals which were once seen frequently in Pavagada are no longer around. Farmers said there was a decline in bird population as well.

“This region is close to the Jayamangali Blackbuck Reserve which is a habitat for the blackbuck as well as the Great Indian Bustard, listed as critically endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature,” said Environment Support Group’s Bhargavi Rao, who is the principal investigator of the Harvard-Kennedy School-supported project Governance of Socio-technical Transformations.

The Karnataka State Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan suggests looking beyond flagship species and protected areas to conserve biodiversity. Bhargavi believes that if the state was committed to the plan, they wouldn’t have come up with a tightly fenced solar park in this area.

Farmers also pointed out a rise in atmospheric temperature and increased rainfall. While it could be part of a larger climate change phenomenon, environmentalists said the changes needed to be studied for a better understanding of the park’s impact.

Halder of Landesa says he feels that the Karnataka Solar Power Development Corporation Limited could have done a few things differently to make the transition just and fair. The presence of an agriculture expert on board to better advise farmers on the land-use change for informed consent is one.

A mapping of skills in the region and programmes to develop skills useful for the park is another. He also says that voices of women, especially Dalit women, were missing during conversations around transitions. “A better understanding of their relationship with the land and what they stand to gain or lose as it transitions were necessary,” he said.

There is concern around life and livelihood in the region after the park is decommissioned. The agreement with the villagers states that the land would be given back to them in the same state as it was acquired.

Environmentalists are certain that heavy concretisation of the land to build the panels have changed the land patterns. Karnataka Solar Power Development Corporation Limited, however, is hopeful about extending the lease period and is certain that the land would be cultivable if it needed to be returned to the farmers. Questions, however, remain as to what would happen to the enormous waste generated during the process.

At the end-of-life stage, if not handled properly, toxic elements from disposed of PV panels can adversely affect ecological systems and the health of those involved in disassembling or dumping the panels, says the study, Renewable Energy to Responsible Energy by Forum for the Future. Due to the lifespan of photovoltaic modules (25 years-30 years) and the failure to design for re-use or recycling from the outset as well as due to the replacement of modules with newer, more efficient ones, India will soon witness large volumes of photovoltaic modules reaching the disposal stage. At this stage, it is crucial to come up with solutions to tackle this impending problem.

Fewer livelihood options

Land is the most critical requirement for utility-scale solar projects that require about five to eight acres of land per megawatt, reveals a study: “Powering Ahead: An assessment of the socio-economic and environmental impacts of large-scale renewable energy projects and an examination of the existing regulatory context” by Asar, an organisation that studies environmental and social challenges India faces as the country transitions to clean and sustainable energy. The Census 2011 revealed that 26.3 crore Indians are directly dependent on the land for their lives and livelihoods and another 300 million earn their livelihood indirectly from farmland, through ancillary activities. Scarcity of barren land often pushes solar projects to farmlands bought or (in this case) leased from farmers.

Before the solar park, villagers grew multiple crops in Pavagada. They also kept livestock and did odd farm jobs in rich farmers’ land to supplement their income. Despite Pavagada being a semi-arid region, they were largely content with agriculture.

“We got very little rain in the years leading up to the park and farmers were beginning to feel worried. If not for that, people wouldn’t have been so ready to part with their land,” said Mahesh, a farmer at Pavagada.

He felt that the state took advantage of the villagers’ predicament. “Some of the village elders now say giving away all the land was not a good idea,” he said. “Future generations will have no ties with farming.”

While many farmers are content with the steady income, there are the ones who rue the loss of their cultural identity. “Some feel that since farming was not bad in the area, the government should ideally have supported it with an irrigation project instead of taking their land away from them,” Pillai told Mongabay-India.

In many cases, large solar parks break up commons. The study says that since roughly 9 crore hectares of the country’s total land is classified as “wasteland” which provide critical ecosystem services and are crucial for people’s lives and livelihoods, land for solar parks in these commons, that can be acquired relatively easily, have a socio-economic impact on local communities.

In the project-affected villages in Pavagada, which is primarily agrarian, almost 80% of large landholdings (10 acres or more) are with rich farmers who are incidentally upper caste, while medium to small landholdings are with poor farmers and most Dalits are landless, according to Pillai.

When large tracts of land were given for the solar park, many sold their livestock for throwaway prices because they had lost grazing grounds. The ones who kept livestock were forced to take them to distant areas for grazing since the fenced solar park had become inaccessible. Some even migrated to other villages for three-four months to graze their livestock. While a few companies are letting male shepherds into the park with their sheep and goats (not cows or buffaloes as they could destroy the solar panels), women are still not allowed inside the park.

Most of the Dalit farmers in these villages are landless. Some like Mache Hanumantha of Vallur have farmed for generations on a two-acre land but do not possess title deeds. Hanumantha has turned to alcohol and gambling after the land was taken away from him for the park, without compensation.

A father of six young children, his single-room house runs on a meagre wage his wife earns by plucking and sorting tomatoes at a farm. “My father used to work here for wages and then, he started tilling the land,” he said. We did not try getting the title deed then. Now the land has been taken over for the park. I have spent about Rs 2,000 to Rs 3,000 to sort the deed issue. I have not received anything till now.”

Social inclusion and procedural and distributional justice are key components in phasing out coal and just transition to the renewable energy sector, said a study by Climate Investment Funds. Since 2011, mostly landless and marginalised communities in Rajasthan, who have been excluded from development planning as they have no title deeds to the government land that they use for grazing, nomadic passages, and funerals, have filed 15 cases against solar plants in the state’s high court. This issue was identified in a 2012 report by the Natural Resources Development Centre and the Council on Energy, Environment and Water which noted that “as the solar energy market matures, it is critical that government policies and (private) developers minimise the impact on the local communities”.

“Is not it ironic that one of the latest and the most modern technologies has kept away one of the oldest professions known to humanity like grazing and growing food,” asked Bhargavi Rao.

Avoiding equity issues

Renewable energy is a relatively new sector and the world over, the talk is on how to centre the transition from fossil fuel to renewable energy around justice. Since it is a nascent technology, this is the right time to address all the inequities and social injustice associated with the fossil fuel industry.

Priya Pillai believes that the time is right to come up with a new energy sector model where justice is delivered to the affected beyond gender, caste or class. “What we are seeing, however, is that governments and the big players are approaching the renewable energy sector the same way fossil fuel transitions were done and this only reaffirms earlier injustice,” she told Mongabay-India.

The way forward will be in adopting more inclusive options like decentralised systems, community-owned models and cooperatives where people and communities own these systems.

Second of a two-part series on socio-ecological issues related to mega solar parks as part of the Internews’ Earth Journalism Network’s Renewable Energy in India: Entrepreneurship, Innovations and Challenges Story Grants for 2021. Read the first part here.

This article first appeared on Mongabay.

Buy an annual Scroll Membership to support independent journalism and get special benefits.

Our journalism is for everyone. But you can get special privileges by buying an annual Scroll Membership. Sign up today!